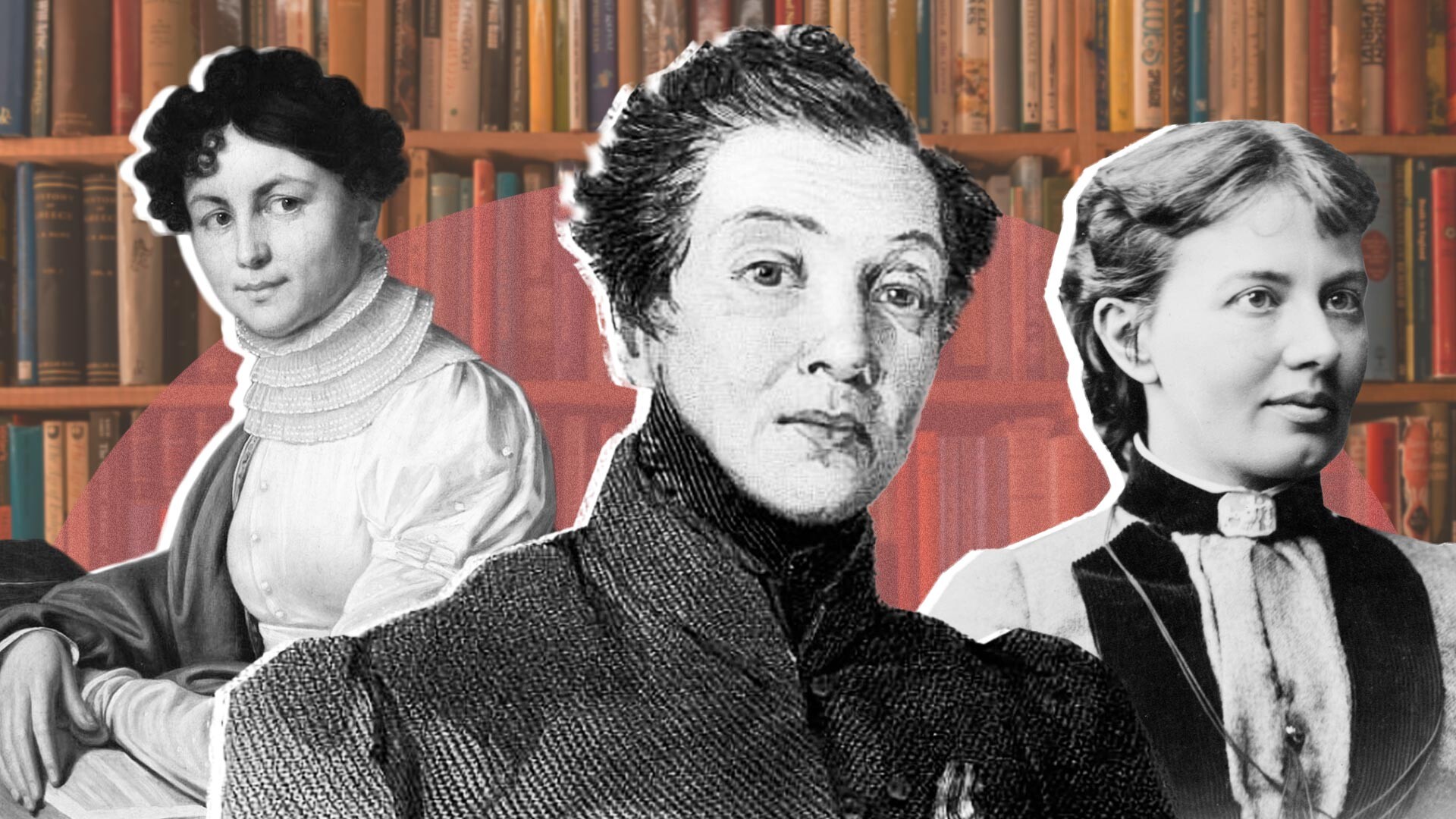

5 FIRST Russian female writers

Women in Russia took up the pen as early as the 18th century - they practiced poetry, translations and fiction (mystical and sentimental novels). Peter the Great’s sister, Princess Natalia Alekseevna, wrote plays for her own theater and the publicistic talents of Catherine the Great are widely known. Here are some of the first ever professional female authors.

1. Natalia Dolgorukaya (1717-1771)

One of the first female writers and memoirists is considered to be Countess Natalia Dolgorukaya. There were real ups and downs in her biography: once a daughter of a high ranking man named Boris Sheremetev, she was a court lady close to Emperor Peter II, but her husband fell into disgrace and she had to follow him to Siberian exile. Eventually, she ended her life becoming a nun.

The memoirs she left are called ‘Notes of Countess Natalia Borisovna Dolgorukaya, daughter of Field Marshal Count Boris Petrovich Sheremetev’. Literary scholar Dmitry Svyatopolk-Mirsky praised her text for the “sincerity of the narration” and the “magnificent purest Russian language”.

2. Anna Bunina (1774-1829)

Anna Bunina is considered the first professional Russian poetess and used to be referred to as the “Russian Sappho” (Writer and Nobel prize winner Ivan Bunin belonged to her family). The most respectful 18th century poets, Nikolai Karamzin and Gavrila Derzhavin, praised Anna for her odes to heroic deeds.

However, the younger contemporaries of the “golden age of Russian poetry” considered her poems old-fashioned and called her a “poetic corpse”. Alexander Pushkin himself sneered at her “nonsense” and “silly poems”. Konstantin Batiushkov maliciously joked, alluding to Sappho’s suicides: “But, to my grief, / You don’t know the way to the sea.”

3. Nadezhda Durova (1783-1866)

The brave cavalry woman served in the army and fought with Napoleonic France, preferring to be called Alexander Alexandrov. Her main work, ‘Notes of a Cavalry Maiden’, was first published by Alexander Pushkin. In fact, it was him who revealed her personality and her gender that she had kept in secret. This audacity made Durova mad, but Pushkin answered her: “Be brave and enter the field of literature as bravely as the one that made you famous.” [meaning the battle field - ed.]

In her “Notes”, Durova wrote about her life and the terrible, hurtful situation in which the women of her time, born essentially to “live and die in slavery”. She tells of her decision at all costs “to separate from the sex, which I thought was under the curse of God”. She also describes how she was tricked into joining the service and depicts the first battles in which she fought.

Read more about Durova’s incredible life story here.

4. Yekaterina Avdeeva (1788-1865)

Unlike most female writers, Avdeeva came from a merchant family, not a noble one, and she didn’t receive any (even home) education. She lived in the city of Irkutsk, not far from Baikal Lake, traveled a lot and wrote one of the first Russian ethnographic books titled: ‘Notes and Remarks on Siberia’ (1837). In it, she recounted stories of everyday life and customs of the locals and also included the local folklore and old Russian songs that she wrote down.

Later, Avdeeva wrote books on housekeeping and folk medicine, a cookbook, collections of songs and also published folk tales for children that she documented. Later still, folklorists and collectors of fairy tales praised her work and the fact that she gave “an authentic record from the mouths of the people”. In 1859, the ‘Literary Fund for Writers’ aid appeared in Russia and granted Avdeeva a pension for the rest of her life.

5. Sofya Kovalevskaya (1850-1891)

Kovalevskaya is first of all famous as the world’s first woman professor of mathematics. But, in Russia, we used to say that a brilliant person is brilliant in everything, so her creative energy was also enough to become a writer. Sofya wrote in Russian and Swedish, as she spent part of her life in Sweden. Her area of interest was the freethinking and youth riots of the 1860s (her novel ‘The Vorontsov Family’ is a case in point) and Russia’s first revolutionary movement of the 1870s.

One of her most famous works is the 1884 novel ‘The Nihilist’. It is based on the true story of Vera Goncharova, Alexander Pushkin’s niece. The young lady decided to marry a stranger who had been accused and convicted of being a revolutionary (and Kovalevskaya was involved in getting permission for this marriage). The story was published in both Swedish and Russian, but was almost immediately banned in Russia. The censor explained that he made a decision because of the author’s sympathy for nihilism, as well as the fact that the book’s cover was “in terrible colors depicting the fate of political criminals and the cruelty of our government against them”.