There are no more than five ceramic artists who work according to the old Gzhel Maiolica technology. Their artworks have little to do with what’s usually associated with Gzhel in the mind of the general public: they are five-colored, with a lubok ornament.

“You have no idea how we arrange exhibitions with these craftsmen,” laughs Valentin Rozanov, one of the leading artists of the Gzhel craft. “‘Please, give us some of your works for an exhibition’, I say. And the artist might answer: ‘listen, I have it all already planned for years; some of my works I haven’t even finished yet, but they’re already sold’.”

Gzhel Maiolica has a complicated production technology. There are others, namely Gzhel semifaience, faience and porcelain, which have been methodically developed over the last couple of centuries. Factories and family workshops produce them. There are also individual craftsmen who have achieved significant recognition in the craft of blue-and-white porcelain. In total, there are about 10 such Gzhel artists. “They have their own section in the State Historical Museum. It’s not a craft anymore, it’s an art form,” Rozanov says.

Such craftsmen work alone on their pieces, throughout the entire cycle of creation: from a lump of clay to the painting, glazing and baking. “A craftsman might pore over his jug for two months, and then it cracks during baking and he’ll have to start over… The percentage of defects in original ceramics reaches 50%; the technology is complex, depending on, literally, if the clay wasn’t of the required quality,” Rozanov says.

So what path did this craft have to take in order to develop from simple pottery to achieving recognition as one of the most authentic Russian folk art styles?

A museum piece.

Valentin RozanovGzhel is the name of an entire region 60 kilometers outside of Moscow that includes about 30 villages. Even before the 1917 Revolution, when Soviet revolutionaries gained power in Russia, this area was listed as the Gzhel Volost of the Bronnitsky Uyezd of the Moscow Governorate. Today, “Gzhelsky Kust” – as the region is called today – is a part of the Moscow Region. Governments come and go, but for the past 700 years this region has been famous for one thing – its clays.

Gzhel Volost never had a social system of landlords or serfdom, as was common in other places in central Russia. But it did have pottery workshops or, to be more precise, hundreds of workshops. Some of these remain a family business to this day, and a few have grown into giant factories that enjoy significant privileges from the state.

Gzhelsky Kust was known from the beginning of the 14th century when the first mention of the Gzhel land appeared in documents – at the time when it was subjugated by the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Even back then, the village locals were active in the craft of pottery. However, their work was quite basic and traditional – they made tableware, as well as other everyday items such as clay drainage pipes, korchagas (giant clay vessels), and toys.

Digging in Gzhel, 2022.

Oleg Tulenev/Gzhelskoe MoreValentin Rozanov says that even today the residents of Gzhel villages, whenever they dig a garden to plant their potatoes, often find 200-300 year-old shards of toys or plates with very basic decoration. “They are simple toys of the same type, similar to Dymkovo toys: horses, bird pennywhistles, bears – such toys were widespread across the entire Russian Plain and, perhaps, had ritual purposes.” Only shards are found in the gardens, manufacturing defects that were discarded. Apart from perhaps 20-30 pieces of tableware, none of the items found are deserving of a place in a museum.

In the 17th century, the people of the Gzhel Volost were assigned to control by the Moscow Pharmaceutical Prikaz (office): the workshops became the official state suppliers of vessels for storing medicine. Back then, pharmaceutical jars and phials were made exclusively from ceramics.

At the same time, in order to escape persecution and Nikon’s reforms, the Old Believers fled to the dense forests and swamps for which this area was well known. The Old Believers, by the way, also fled to the forests of Zavolzhye in the 17th century. But there, they brought the craft of gold painting, known nowadays as khokhloma.

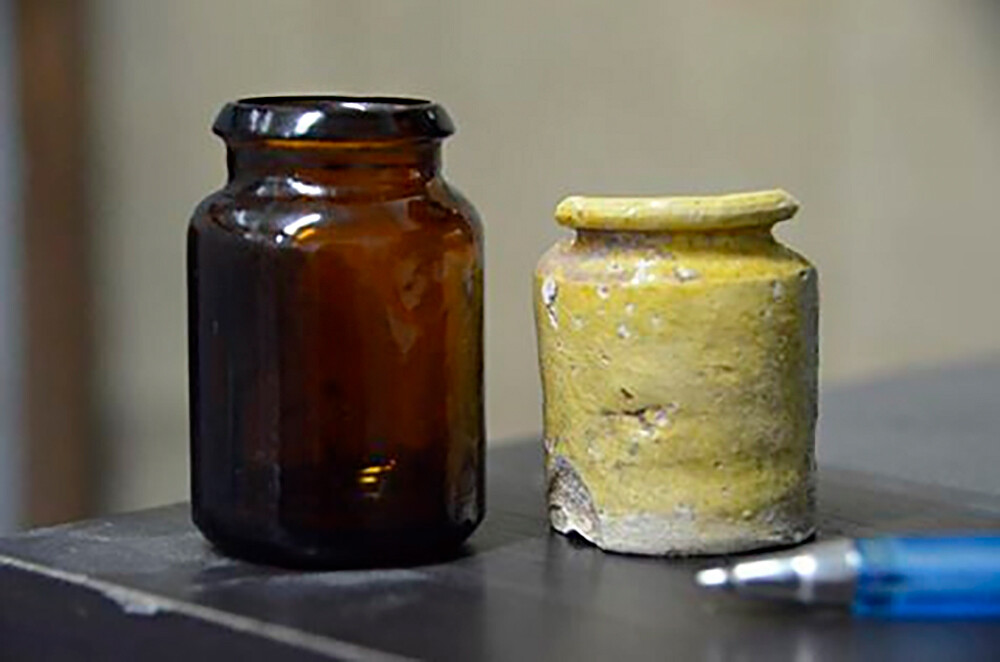

Glass jars of XVIII and XX centuries.

Oleg Tulenev/Gzhelskoe More“People do what they can to feed themselves,” Rozanov says. “Half of the trees are cut down now, but back then there were only forests around, well-suited for hiding. And dozens of clay types can be found on the surface: from white clay to brown clay. Like it or not, clay had to be used for technical purposes. The Old Believers lived in communities, and built churches. They always brought their handicrafts along, they liked working with their hands. Thanks to this and the clays, the Gzhel land turned into a center of ceramics production.”

There are several theories for the origins of the word “gzhel”. A widespread but false opinion is that gzhel derives from “zhech” (to burn something) since the pottery was tempered in an oven.

The most likely version is that it’s derived from the river Gzhelka flowing through the territory of the Bronnitsky Uyezd, and which is the main waterway in this area.

In Old Slavonic, “gzhel” means gusli (musical instrument). By the way, there is a place called Guslitsa near Gzhelsky Kust.

There’s another Slavic, or more precisely Polish, version: gżegżółka (gzhegzhelika) means a cuckoo. There are a lot of such birds in the local forests.

Gzhel products, of course, were not blue nor porcelain in the beginning. First, simple terracotta or “burned earth” appeared. Kids still like to make it by themselves: in bricks they bake in a Russian oven, or even over a campfire, tableware or toys sculpted by hand from red clay.

The solidified clay was very porous, and liquid could seep through the sides. Potters came up with various ways to temper it. “Boiled” ceramics were dipped in a liquid solution – similar to pancake batter – straight after baking and while still hot. During “milking”, the tableware was literally submerged in milk before baking.

In the 17th century, Peter the Great, who loved the Netherlands and its blue ceramic tiles, introduced the fashion of plates with a blue border. In the 18th century, the fame of colored European Maiolica – porous ceramics covered with glazing – reached Gzhel. Aristocratic courts eagerly purchased it, but the production technology was expensive and complex. The Gzhelians began looking for recipes and ways of simplifying and improving the production. As a result, the “Gzhel Maiolica” was born: five-colored, with an earthy texture and lubok ornaments.

Examples of museum-quality maiolica have survived to our day, including kvassniks (vessels for kvass) with sculpted handles and a hole in the middle. “There’s speculation that these holes were made so that a piece of ice can be put in, wrapped in cloth, and to cool the kvass,” Rozanov explains. “Some believed that the hole was needed to put several kvassniks on one’s arm when serving guests at the time. For us artists, this hole is a decorative element.”

Kvassniks, XVIII century.

Oleg Tulenev/Gzhelskoe MoreRozanov has been studying the Gzhel craft for many years and he concluded that no one used kvassniks back then; they were specifically collector’s tableware. Along with other researchers, Rozanov tried to understand, by studying the collections of large museums, what kvassniks were used for. “We looked inside with a flashlight. The bottom was unglazed: there were drips of glazing, clay, fingerprints, and dust that had been gathering there since the 18th century – no one cleaned them. And the clay was light: if liquids were poured into it, the clay would darken. There’s no way anyone can get inside and clean the vessel. Those things were purely decorative, standing on shelves. They were a dominant element of the interior. The Romanovs collected such things; we saw kvassniks in the Russian State Museum. They were kept and preserved like jewels.”

Along with maiolica, other branches of the Gzhel craft developed: semifaience, faience, and porcelain. Gzhelians were looking for the recipes of foreign ceramics that were highly prized in Russia and which sold for a lot of money. That’s how semifaience was born: an exclusively Gzhelian ceramic. It was more crude than European faience, but thinner and less porous. Craftsmen learned to decorate the surface so well that Gzhel semifaience took a special place in the craft. Then, thin faience emerged. As for porcelain, Chinese and later European porcelain was worth its weight in gold in Russia.

Peasant tableware, from the factories of the Kuznetsovs and Fartalny, faience, late 19th century.

Oleg Tulenev/Gzhelskoe More“The Chinese kept their art of porcelain a secret, and Germany eventually set up its own secret production in order to try and replicate it,” Rozanov explains. “China uses pure components, straight from the earth. They took kaolin and stone, broke it up and mixed it – and you get porcelain. The Europeans also began to select materials from available resources. When porcelain made it to Russia, the locals also began to invent their own variation of the recipe. That’s why different countries have different porcelain. Gzhel had hundreds of factories and workshops. Some stayed at the pottery level, making simple tableware. Those who were smarter opened porcelain production with expensive equipment.”

Partially because of porcelain, Gzhel stayed blue. Fashion for white-and-blue painting returned in the 19th century. The thing is, porcelain is baked at a very high temperature, and the majority of pigments usual for maiolica – brown, green, orange – eventually fade. Cobalt that produces blue pigment doesn’t fade. Quality clay produces the white of the background after baking.

Roses are one of the most popular and famous motifs in applied art, not just for Gzhel but also for the entirety of world culture. Rozanov remarked that,“Roses in Gzhel are closed, painted with three-four strokes, every artist has their own style; we can recognize the author from first glance, but still never be able to replicate his rose. It’s not a simple daisy; it’s a noble, precious and rare flower, people have always strived for all things luxurious. Artists put a different amount of paint on two sides of the brush: with just one stroke they give it a shade and depth – that’s how the paint is distributed with a circular stroke – just one.”

Tableware by Valentin Rozanov.

Valentin RozanovUnfortunately, at the beginning of the 20th century, due to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of mass production, national handicrafts began to die off. Factories were nationalized, and the means of production were left without owners. Men were sent to war, which was a huge problem because men exclusively made ceramics in Gzhel, “People say that until the beginning of the 20th century men did everything, while women did all the housekeeping,” Rozanov adds. “Men in our villages worked 14 hours per day, so they went to their workplaces and lived as a community, returning home on weekends or during holidays.”

In the 1940s, art historian Alexander Saltykov was sent to work in Gzhel after spending time in a Soviet prison camp, and he began to revive the craft. He gathered some of the old workers, restored the technology methodology and process. Later in Moscow, he added Gzhel ceramics to museum collections and organized archaeological excavations. The most famous artist, Natalia Bessarabova, worked under his leadership, and together they created the Gzhel “stroke alphabet.” Parallel to this, pottery-making began to be taught in colleges. Also, porcelain became an exclusively women’s craft. When Rozanov came to a Gzhel factory to work in 1974, he was the only man among female workers.

Today, a state university operates in Gzhel with a department of fine arts and folk art culture. The companies that are certified and support folk art enjoy a tax-exempt status. The government also helps to provide funding for large exhibitions. Professional Gzhel artists still fight for the purity of their craft. “Who crafts it all? There are a lot of workshops. We also see that there are good works and crude ones. We fight against unscrupulous producers. They discredit Gzhel, dumping poor-quality items onto the market,” says Rozanov, who is convinced that the craft won’t die.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox