One day a peasant fed the Firebird, and in gratitude the Firebird turned an ordinary wooden bowl into a gold one. This, according to legend, is how one of the most recognizable Russian designs, known as Khokhloma - the tableware painted in red, black and gold colors - first came into being.

Ladle in the shape of a cockerel

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinThis old variety of handicraft is more than 300 years old. It is named after one of the places where it was widespread - the village of Khokhloma in the Nizhny Novgorod Region. In actual fact, the painting style did not originate in Khokhloma but in dozens of villages around Zavolzhye (the Trans-Volga region east of the River Volga) in what is today Nizhny Novgorod Region's Koverninsky District. Thousands of people lived along the River Uzola in the villages of Bolshiye Bezdeli, Malyye Bezdeli, Mokushino, Khryashchi and Kovernino itself, which is regarded as the birthplace of Khokhloma - a fact reflected in Kovernino's coat of arms. Later they formed artels (associations of craftsmen) that produced wares in the Khokhloma painting style. And in Khokhloma itself there was a famous market to which village craftsmen brought their wares.

Barrel-shaped jar

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinA curious fact - the word "khokhloma" (familiar for Russian speakers) is in fact pronounced with the stress on the first syllable. It's all to do with toponymy: The village of Khokhloma and the local river Khokhlomka are also pronounced with the stress on the first syllable. Hence, the painting style is KhOkhloma.

Bratina bowl

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinIn the homes of many Russians, spoons painted in the Khokhloma style are the most frequently encountered items. They are cared for and passed on to the grandchildren of the family, who at kindergarten and school learn music by using a couple of the spoons as percussion instruments in folk ensembles.

Dish

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinOther wares frequently to be found in the display cabinets of Russian homes are cut glass objects from the town of Gus-Khrustalny in the Vladimir Region and Gzhel items painted on china, which, reminiscent of Delftware, are another of Russia's "showpiece" products. Khokhloma tableware is made of wood and nowadays has fallen out of everyday use.

Dinner set

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinThus, Khokhloma articles are by and large bought as souvenirs. This is a pity, says one of the most prominent master craftsmen of Khokhloma painting, People's Artist of Russia Nikolai Gushchin, himself descended from a family of Khokhloma painters. Unlike china, Khokhloma tableware is resistant to temperature fluctuations. Its painted decoration won't crack even after being kept in the freezer, something that cannot be said of china. Still, you wouldn't put Khokhloma wares in the microwave because they would start sparking owing to the special painting technique - Khokhloma tableware has metal among the ingredients that go into making it.

People's Artist of Russia Nikolai Gushchin

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinThe dense forests and impassable swamps of the Novgorod Region were a refuge for fugitive peasants and soldiers since the times of Old Russia. From the 17th century onwards, in the wake of Patriarch Nikon's reforms, Old Believers started to flee there. Patriarch Nikon changed the Orthodox liturgy and church service books to bring them into line with contemporary Greek ones Those who didn't accept the reforms were persecuted, or left of their own accord. The "old-style" believers, or Old Believers, looked for locations where they were bound to remain undiscovered.

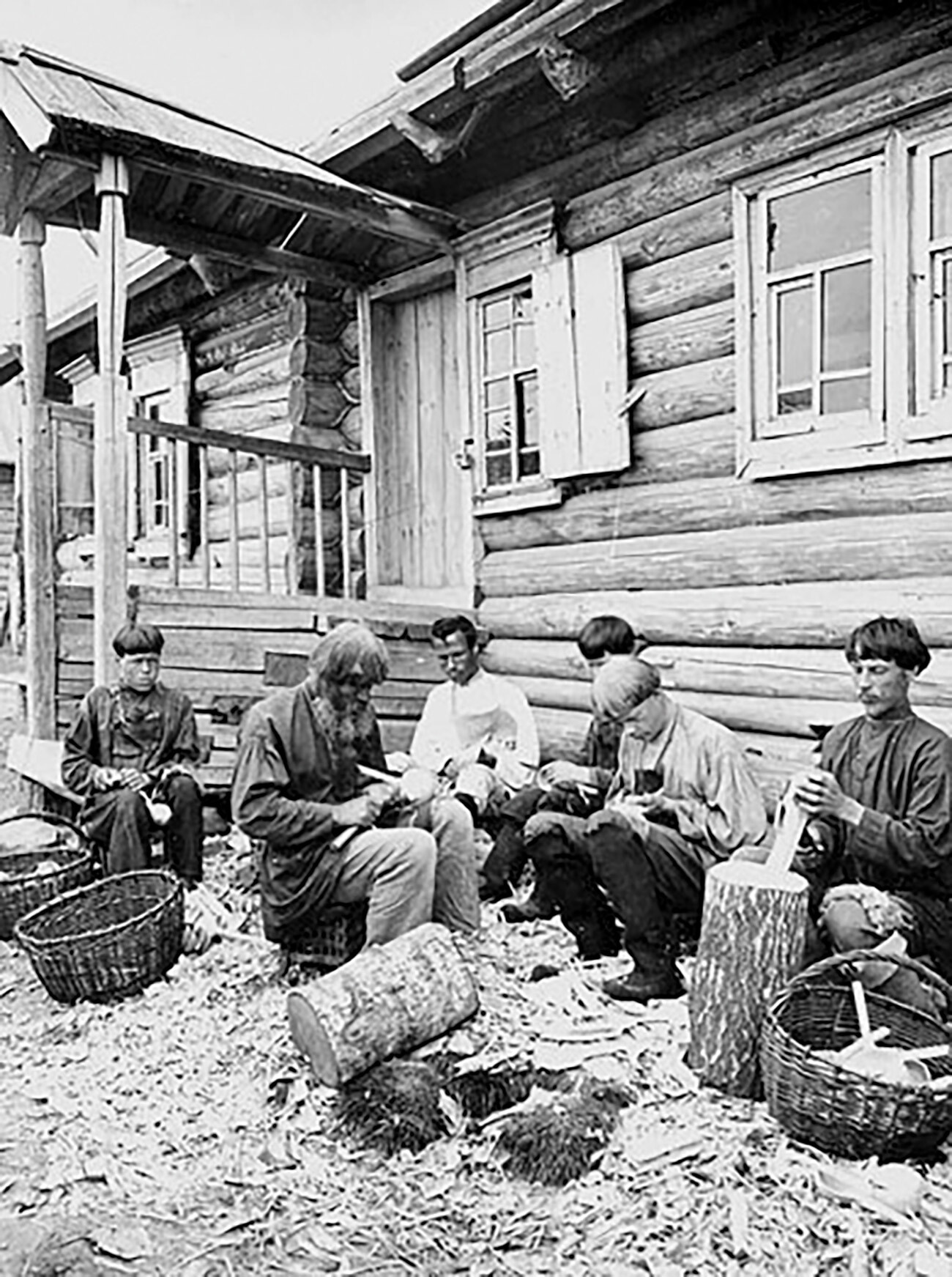

Early 20th century crafstmen

Association of Russia's Folk Art CraftsThey brought with them the secret of gilding and painting the ornamental metal covers of icons (oklads), and this technique was later transferred to tableware. Artisan turners and wood carvers went with them. "The land was barren," according to Nikolai Gushchin, "and in winter people had to occupy themselves with something, so they spent the long cold evenings trying to make extra earnings for the family".

Early 20th century crafstmen

Association of Russia's Folk Art CraftsWooden crockery and furniture were at the center of everyday life in Russia. In the 19th century, the "Russian style" came into fashion and interest in handicrafts greatly increased. Empress Maria Feodorovna learned about Khokhloma.

Khokhloma tableware was brought to the All-Russia Industrial and Art Exhibition of 1853 in Moscow and, in 1889, to the World's Fair in Paris, where it was awarded a Grand Prix. Since then foreigners have fallen in love with it too. "In addition, this crockery was not expensive for them," Gushchin explains. "At other fairs or in their own countries they could make good money from reselling it." A hundred kilometers from the Khokhloma market was Nizhny Novgorod, with its fair, the largest in tsarist Russia, and the River Volga, the main trading artery of the Trans-Volga region. From there merchants took Khokhloma tableware all over Russia and - via Arkhangelsk - abroad.

Apart from the story of the Firebird turning a wooden bowl into a gold one, there is another legend about Khokhloma. The icon painter Andrey Loskut is said to have fled deep into the forest to evade Patriarch Nikon's reforms and to have painted wares "in the old style" there. When soldiers were sent after him, Loskut burned down his cottage with himself in it. That is why there is a "fiery" design in gold and red flickering on the black vessels.

Bowl

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinKhokhloma craftsman Nikolai Gushchin takes a skeptical view of the legends. "They are all fairy tales to kindle interest in the craft," he said. In actual fact, the coloring and the botanical motifs of Khokhloma painting are completely explicable in terms of the powers of observation of the craftsmen, the features of the natural world around them and the very techniques employed in the making of wooden tableware.

"Black, red and gold are the principal colors of Khokhloma painting. Additional colors are yellow, orange, green and brown. There were several shades of green. This range of colors was established over many decades," Nikolai Gushchin says. "The tableware was hardened off in a kiln. And only the oil paints that did not lose their color survived in the palette. Today we say "black background", but in my childhood we always used to call it "black earth" - or "red earth" if the painting was on a red background. The designs were based on popular motifs: The people who lived in our district observed nature. They saw the way a snowdrop flower blossoms, how a rowanberry ripens, how a blackcurrant leaf opens up and how its berries appear. Powers of observation, an awareness of the world and one's surroundings - all this contributed to the painting technique. They learned from nature."

Barrel-shaped jar

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinAnd the principal "secret" of Khokhloma is that gold was never used in its production - neither real gold, nor paint imitating it. Initially, the craftsmen would use silver and then tin to create a warm gleam. The wares were expensive and not everyone could afford tin: The articles were not entirely coated with tin, which was only applied to those areas where the decoration was to be golden. These kinds of wares were frequently served at feasts among the upper classes, and they were supplied by monasteries, which ordered such golden tableware from villages, paying the cost of the expensive tin. Today aluminum powder is used to make Khokhloma wares.

Khokhloma factory worker

Association of Russia's Folk Art CraftsTo make an item of Khokhloma ware, the first stage is to "strike the blocks" ("bit baklushi"- also a Russian set idiom meaning "to twiddle one's thumbs"). This involves securing rough blocks of wood to the clamping chuck of a lathe. This is why the items are always round in shape - they are made on a lathe. After being shaped, the white intermediate article - the so-called "white blank" - is primed to fill the grain of the wood, thus preventing it from absorbing the components used in the metallic treatment. The priming is buffed with coarse cloth and coated with several layers of boiled oil (linseed). And when the semi-finished item has dried to a "slight tackiness" - in other words, it sticks only lightly to the hand - aluminum powder is rubbed into it. After that, it goes off to be decorated. "When we coat an item in lacquer and harden it off in the kiln, the aluminum shows through the yellowish lacquer coating and imparts a warm, honey-colored, golden hue," Nikolay Gushchin says.

Khokhloma factory worker

Association of Russia's Folk Art CraftsThere are two types of Khokhloma painting: the background technique and the surface technique. "With the surface method, we employ free variations of the brush to decorate the surface of the item, on top of the gold," the craftsman says. "Meanwhile, the "background painting" technique is divided into two subtypes - background painting itself and what is known as "Kudrina" [this technique, whose name is derived from the word "kudryavy" meaning "curly" or "full of flourishes", employs stylized "curling" ornamentation]. First, the contours of the decoration are drawn on the item with a fine brush, and then black or red paint is used to fill in the background around the design. That way, the gold remains only in the parts of the decoration left uncovered."

The Khokhloma painters passed on their skills from generation to generation, and taught young people using the "placement" method whereby three or four apprentices would be placed with a single craftsman. Families in villages were always large. Only a handful of individuals would head for the towns. In the Soviet period, girls would go to learn to be artists after completing eight grades of school, while before going into the army the boys would train to be lathe operators or woodworkers. Today the situation is different: People no longer return to the villages from the towns.

Semyonov School of Khokhloma

Association of Russia's Folk Art CraftsIn the 20th century, production facilities were built in Kovernino and neighboring Semyonov, where the railway line passed. A painting school was opened in Semyonov; it has now become a technical college. Today Semyonov is regarded as Khokhloma's "second home" and, whereas all that remains of the Kovernino factory is a Khokhloma production unit in the village of Sukhonoska and a factory making clay toys, the Semyonov factory is geared entirely to the production of Khokhloma. Admittedly, they don't just make the traditional wares. They sell souvenir-grade merchandise in a varied range of colors: Light blue samovars and gray-pink dishes which only resemble Kokhloma from a distance. "When we now see items in white, mauve, dark blue and pink colors, we realize, without even checking what they are like in daily use, that they are fakes," says Nikolai Gushchin. "These wares have not been hardened off in the kiln. They are merely acrylic paints coated with acrylic lacquer. The colors would be destroyed in the kiln."

Materials relating to work on Kokhloma

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinThe prestige of Khokhloma painting was severely undermined in the 2000s, he laments. "Everyone was trying to make money from souvenirs, painting dark blue skulls in the Khokhloma style," he says. "The colors would bleed through the layer of lacquer and come off on your hands, and the paint would flake, because the articles hadn't been properly primed. At the same time, traditional Khokhloma painting continued to be applied to the range of painted tableware for household use, exactly as before… In order to get people to appreciate traditional crafts you have to tell them about the work of master craftsmen, give masterclasses not based on cheap and cheerful methods but using the old techniques, mount exhibitions and educate the consumer. I go into a shop and am astonished, and the shopkeeper tells me that everyone is buying the blue skulls. Well, people are going to be buying what you're selling, but our job is to implant good taste," Nikolai Gushchin says with conviction.

People's Artist of Russia Nikolai Gushchin during a masterclass

Courtesy of Nikolai GushchinDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox