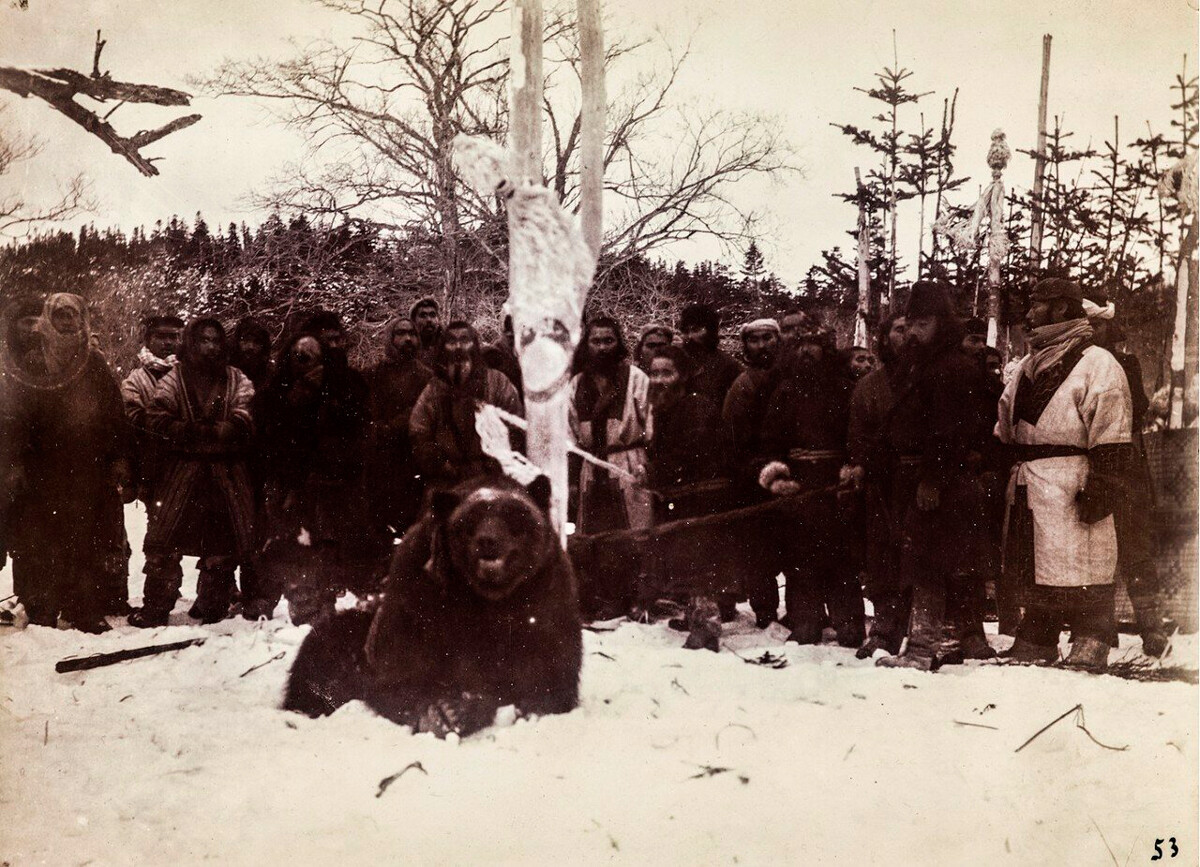

Bear worship is a peculiar cultural phenomenon which was once widespread in Transbaikal and Amur Region. It can still be seen today among the representatives of small ethnic peoples who still preserve their traditional way of life.

Engraving showing a family of indigenous people, possibly from Siberia. In the background is a recently killed bear.

SSPL/Getty ImagesThe Evenks, Khanty, Mansi, Nivkhs, Ulchis and many other indigenous peoples live in Siberia. Today, some of them still believe that everyone has their own ancestor animal, which not only gave birth to their family, but also accompanies them throughout their lives. Often these animals were widespread in the region of habitat, thanks to which people have “survived” in difficult situations. One of these animals was the polar bear. There are many traditions associated with the bear cult, which are still observed in a number of small ethnic groups.

Competition in archery among the Nivkh, 1970, Sakhalin.

Chernysh/SputnikFor example, some Evenks (an indigenous population of Eastern Siberia) call the bear ‘amikan’ (grandfather, old man), ‘amakchi’ (great-grandfather), ‘ami’ (father) and other words associated with the family. One of the main activities of the Evenks is hunting. Every winter, they leave their villages and go to remote parts of the taiga. Despite the sacredness of the bear, it also becomes a target - primarily because of its valuable fat, which has medicinal properties.

The Evenks believe that each hunter can kill only a strictly defined number of bears and that if this number is exceeded, the hunter will be punished by the higher powers and himself will be deprived of life. That is why the process of killing an animal has taken on ritual traits. The hunter apologizes to the beast and explains why he started the hunt. The meat is sometimes stored for further use and sometimes eaten shortly after.

After the hunt, the bear is given a ceremonial funeral. Its bones and head are placed in a special log cabin, which is built in the direction in which the bear walked before it was killed. The Evenki believe that, after this ceremony, they will not be haunted by the spirit of the killed animal. Later on, they hold a ritual called ‘takamin’ (meaning “to deceive a bear”). All participants of the hunt share a meal containing the meat of the killed bear and wish the hunter who killed the bear good luck, health and large herds of reindeer. The hunter is the last to start the meal and the eyes of the animal are hung in front of his tent.

A hunter demonstrates a skin of a killed bear, 1973, Republic of Buryatia.

V.Belokolodov/SputnikThere was also a bear cult among the Buryats. Like the Evenks, they consider the beast to be a “member of the family” and call it ‘babagai’, a common word for addressing elders. Buryat folklore gave rise to the two most common mythical versions of the bear’s origin. The first suggested that the hunter voluntarily turned into a bear, because of the envy and malice of those around him. According to the second, the man was turned into a bear for his misdeeds - greed, cruelty and mockery. Because of the combination of shamanism and totemism, the Buryats believed that the bear was also a shaman, the most powerful of all.

Evenks. A hunter with equipment, 1912.

Kunstkamera/Russia in photoThe most striking manifestation of the bear cult is the bear feast. Each nation has its own legend about its origins. The Evenks have the following legend: a young girl, who found herself in the forest, fell into a bear den and spent the winter there. In the spring, after returning home, she gave birth to a baby bear, which she raised as a son and, some time later, she married and gave birth to a boy. When the brothers grew up, they decided to fight and the man killed the bear. The latter, dying, told his brother how to hunt and bury bears properly.

The legends may differ, but all have a common motive - the bear chooses a person to whom it passes on sacred knowledge about hunting and the proper treatment of its kin.

The bear festive of the Ainu indigenous people. The second day.

Bronislav Pilsudsky/Public DomainFor some indigenous peoples, the feast was timed to coincide with a successful bear hunt, for others it was cyclical and took place in January or February. In the first case, the central event was a meal - the meat of a killed bear was eaten at night, from the beginning to the end of the feast, with one of the hunter’s relatives eating raw meat to gain bear strength, wisdom and habits. In between meals, there were dances, songs and games.

The bear festive of the Ainu indigenous people. The third day.

Bronislav Pilsudsky/Public DomainThe regular holiday was not connected with hunting: sometimes, it was celebrated as a funeral of a deceased relative whose soul had supposedly passed into the bear and, sometimes, it was celebrated as a ritual feast in which the tribe thanked and praised the spirits. A bear cub would be found in the forest and raised in a cage for three years. In the beginning, it would be breastfed like a baby and called a “son”.

At the end of the three years, the bear owner would offer wine to the household spirits and apologize for not being able to keep the bear any longer. Then, together with the guests, he would go to the cage and treat the beast - it would be released and taken around the houses, whose owners would present it with food and take a bow to bring prosperity to the house.

The bear would then be slaughtered and skinned at a specially prepared site, with its head and hide lowered into the house through the chimney. After cooking, dinner was served: boiled bear meat, which was removed from the cauldron with a ladle bearing the bear’s image and served on a special wooden dish. After the meal, the bear bones would be collected and given to the hosts with some presents. Before the feast was over, the elders would sit for a whole night near the bear’s skull and talk to it.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox