A look at Russian scholarship of the Tamil language

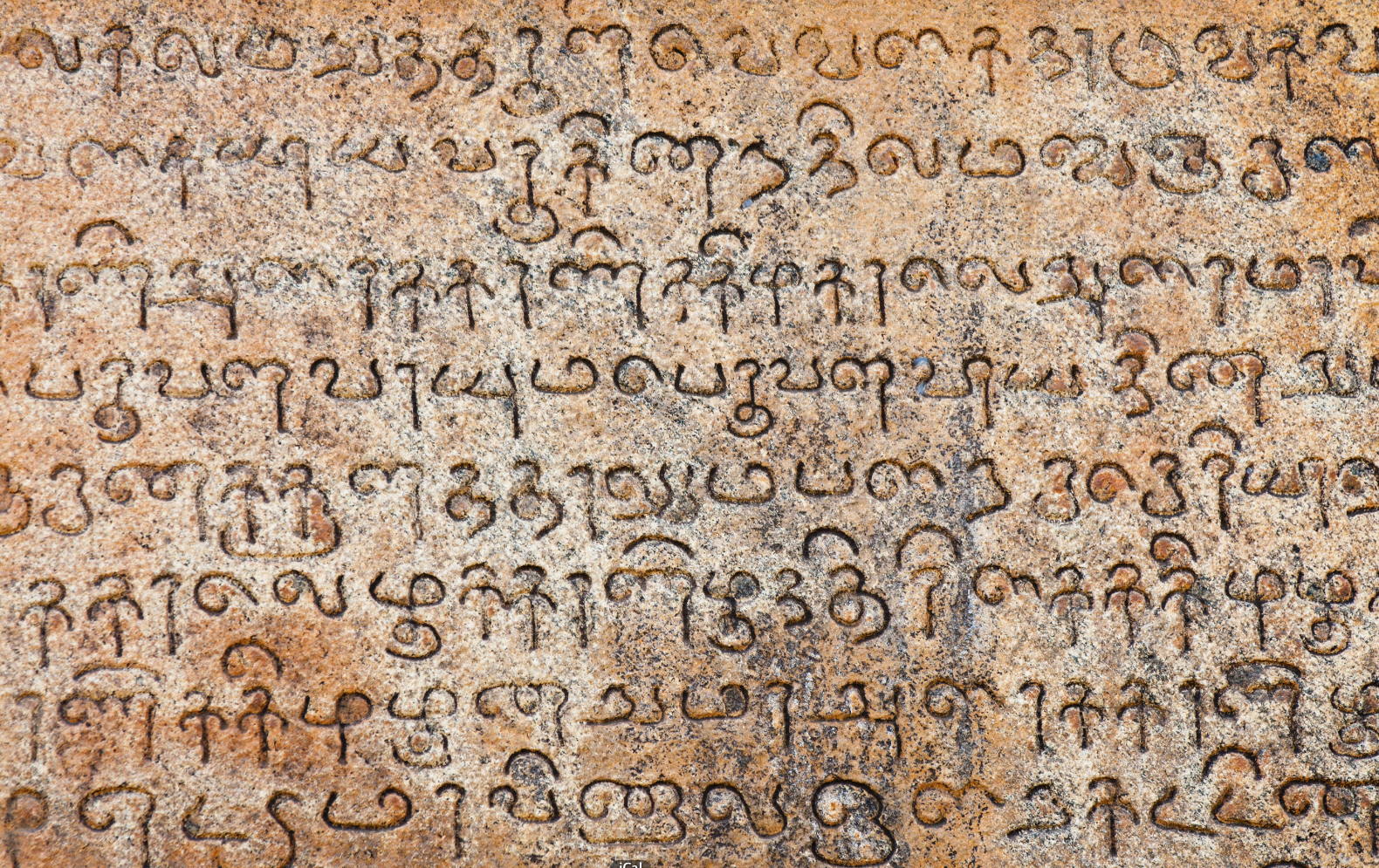

An inscription in a temple in Thanjavur. Russian linguists have long shown a deep interest in Tamil.

Shutterstock/Legion MediaA growing interest in India’s wide range of languages in the 19th and 20th centuries led to several Russian scholars conducting research on the Tamil language. Russian orientalist Vladimir Makarenko, who co-compiled the first Russian-Malayalam and Russian-Kannada dictionaries and was a Tamil scholar, presented several papers on the Tamil language, most notably on Tamil loan words in Southeast Asian languages and South Indian cultural influences in Southeast Asia.

Russia’s earliest visitors to India

Russia came into contact with the Tamil as early as the 15th century when Afanasy Nikitin visited India.

“In Nikitin's notes for the first time is encountered in Russian such a Tamil word as panam or fanam (ancient gold coin); here one can also see the word sandal which originates from sandanam, sandam or Sanskrit chandan,” Makarenko wrote in a 1965 paper titled ‘Tamilogical Studies in Russia and the Soviet Union.’ “Besides, the following words such as Tamil kurundam, sumhada or sumbala, innchi, Malayalam achacha and achchhan can be found in his notes. It goes without saving that Nikitin's notes represent the earliest source of general data about Indian culture as a whole, of the customs and habits of her people, and the economic and political situation of the country covering the second half of the 15th century.”

Other travellers were also fascinated with the Tamil language. Composer, poet and linguist Gerasim Lebedev, who was one of the founders of Russian Indology, actually took Tamil lessons. In 1785, he started learning the ancient language in Madras (now Chennai).

Lebedev was the first Russian Orientalist to study Tamil in Tamil Nadu. “He began to study the Tamil language elaborating his own system of transcription of Tamil sounds; Russian print being used for this purpose,” Makarenko wrote.

Lebedev would go on to study Sanskrit and Bengali (a language he mastered), and his exploits in India inspired a totally new generation of Indologists and Tamil specialists in Russia.

Russian publications on the Tamil language

Tamil was popularized among the scholar community in St. Petersburg in the late 19th century by two Dravidologists- Karl Graul and Sergey Bulich.

“Bulich published a two-volume Account of the History of Linguistics in Russia, gathered a big collection of works on Dravidian linguistic and wrote several articles on Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam languages,” Makarenko wrote. “The most interesting is the article ‘The Tamil Language,’ where Bulich paid much attention to colloquial Tamil (koduntamil). “

Russian research on Tamil continued through the 20th century. The Soviet government, which was eager to build ties with India, encouraged scholars to learn more about Dravidian languages. One of the Tamil language’s best friends in Moscow in the 20th century was Mikhail Andronov, who wrote ‘A grammar of modern and classical Tamil’ in 1961, ‘The etymology of Tamil, Dravidian’ in 1977 and ‘A comparative grammar of the Dravidian languages in 1978.’ He was also among the first academicians to write a book on the Brahui language, a Dravidian language spoken in Baluchistan.

Russian-Tamil dictionary

Despite the fact that hundreds of papers and books on Tamil were published in Moscow from the late 19th century onwards, it wasn’t until 1960 that a Russian-Tamil dictionary was published.

The dictionary was co-compiled by scholar, linguist and philosopher Alexander Piatigorsky. A student of George Roercich at Moscow’s Institute of Oriental Studies, Piatigorsky specialized in Tamil and Hindi studies. Sanskrit, Pali and Tibetan also figured among the 10 languages that Piatigorsky could speak. Despite his lifelong passion for Tamil, the philosopher’s main area of interest was Buddhism. He left Russia in the 1970s and moved to Britain. While working as a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, Piatigorsky wrote several books on Buddhism and visited India regularly until his death in 2009.

The 38,000-word dictionary was co-compiled with Semyon Rudin, a Hindi and Tamil professor in St. Petersburg. Rudin taught himself Tamil before formally studying under Professor Adilaxmi, the first Indian to teach Tamil and Telugu in Russia. She taught the South Indian languages at the Oriental faculty of Leningrad University (now St. Petersburg University).

Rudin’s contribution to the Tamil language was recognized by the Tamil Writer’s Association, which awarded him a medal.

Post-1991

Russian government funding for Indian languages drastically reduced after the fall of the Soviet Union. This has been combined with a fall in interest for Indian regional languages. It’s only a small number of students that now enroll for once-prestigious courses in Indian languages in Russian universities.

A Moscow-based academician told RIR on the condition of anonymity that it was only a matter of time before teaching of several Indian regional languages is completely discontinued. “There is still a great interest in India but the younger generation is now communicating with Indians directly in English, and we have almost lost our competitive advantage in India’s great languages,” the academician said.

The professor believes the best way ahead is to collaborate with Indian universities invite research scholars on exchange programs where they share their knowledge on languages like Tamil and at the same time help the Russian universities preserve and spread their existing scholarly work. “This would also be a good way for Indian scholars to get acquainted with Russia and learn Russian,” the academician said.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox