The ruble’s journey through time, from the Middle Ages to the present day

Starting from the 13th century, governments of different countries measured their national currency in terms of its real equivalent value in either copper, silver or gold. By the end of the 19th century, gold had become the clear winner in the battle for the role of key currency backer.

Centuries later, however, in the 1930s, the world gradually began to abandon the gold backing of currencies, and in the early 1970s, the "gold standard" was abolished completely. For the last 40 years, the cost of money, as well as the frequency of its issue, depends on the state of the economy, market expectations and decisions taken by a country’s central bank.

The Russian ruble has generally followed the trends of world monetary history. It has been backed by silver, copper, gold, and since the mid-1970s, when Soviet drilling platforms began to produce vast quantities of oil, has become a “petrocurrency”, directly dependent on the value of the black gold. Since world oil prices are not known for their stability and are prone to sudden changes – along with world gold prices – it is no great surprise that in the 20th century the ruble endured six monetary reforms, eight redenominations and a series of cases of hyperinflation, when it lost more than 200 percent of its value in just a couple of years.

Of course, changes in oil or gold prices are not the only factors that provoke the ups and downs of currencies, and we should not forget the attendant economic and political factors.

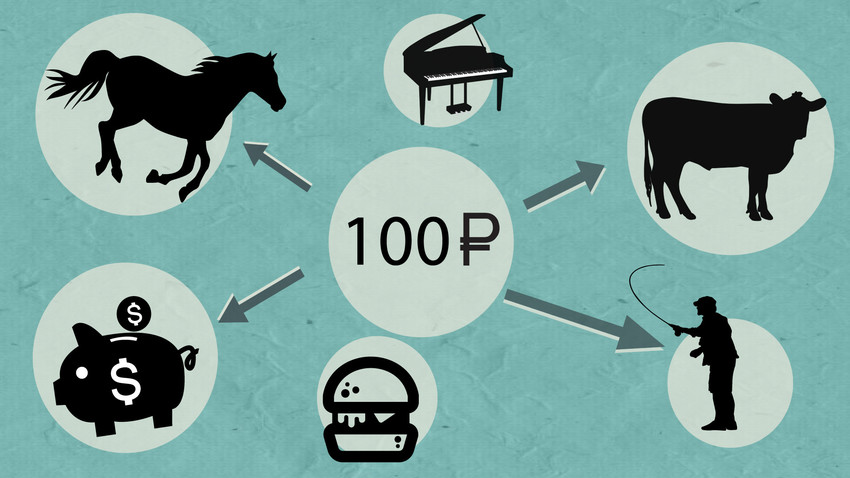

With this in mind, Russia Beyond has composed a five-century retrospective of the ruble, revealing the story of the country’s long quest to modernize its monetary system and acquire a stable currency, as well as showing the purchasing power of the ruble over the course of the last 500 years – as measured against the U.S. dollar. What could be bought with 100 copper rubles in 1666? What would 100 Soviet rubles buy you in 1920s? Read on to find out.

* As the U.S. dollar first appeared on Aug. 8, 1786, the conversion from rubles into dollars in the 16th and 17th centuries is not possible.

Silver ruble, 1534:

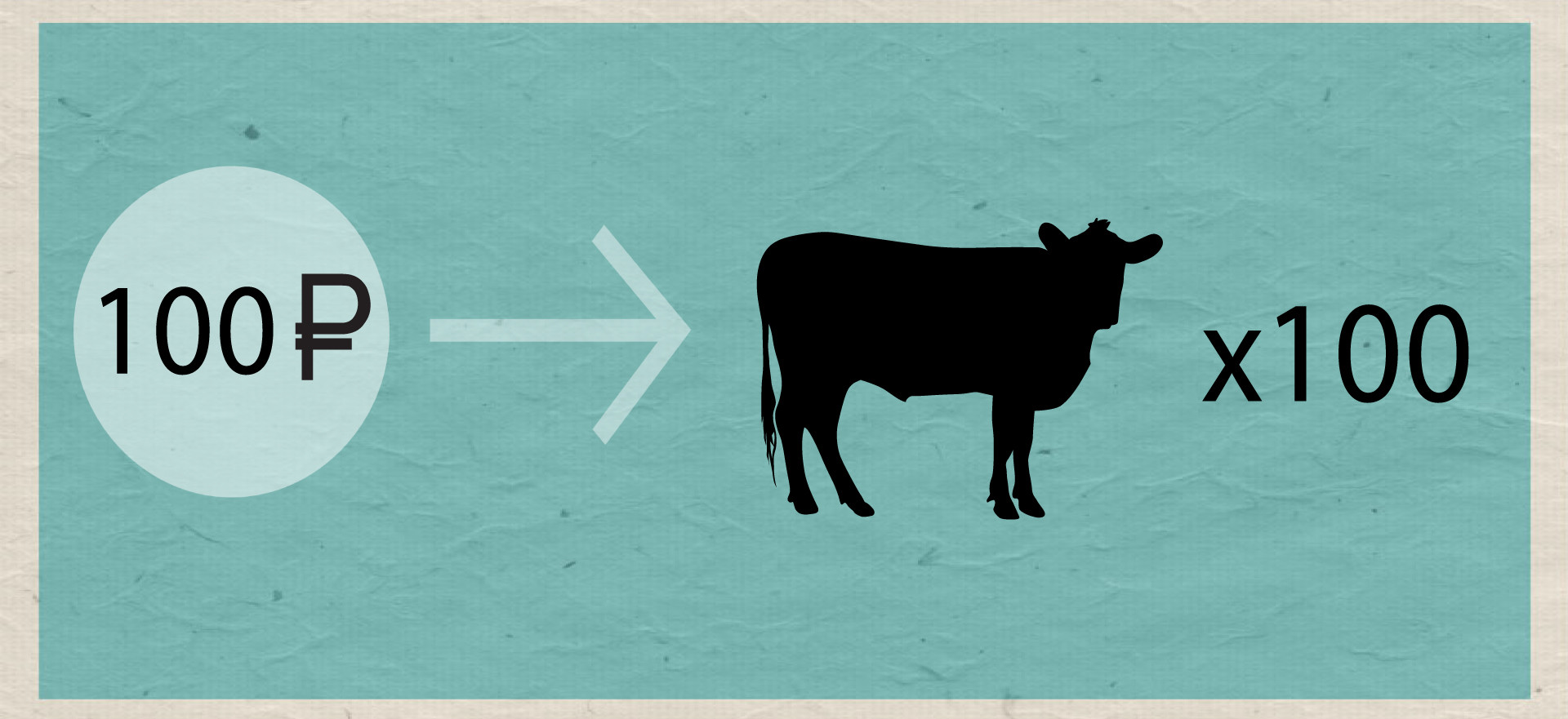

100 rubles = 100 cows or 100 horses

The first Russian monetary system appeared thanks to a young Lithuanian princess, Elena Glinskaya, mother of Ivan the Terrible, she was at the head of the state in the 1530s. At that time Russia faced a financial crisis caused by the lack of a national monetary system and a market flooded by counterfeit coinage. Glinskaya ordered the minting of coins that were more difficult to forge, in so doing establishing the silver ruble as the basic item of circulation and Russia’s first hard currency.

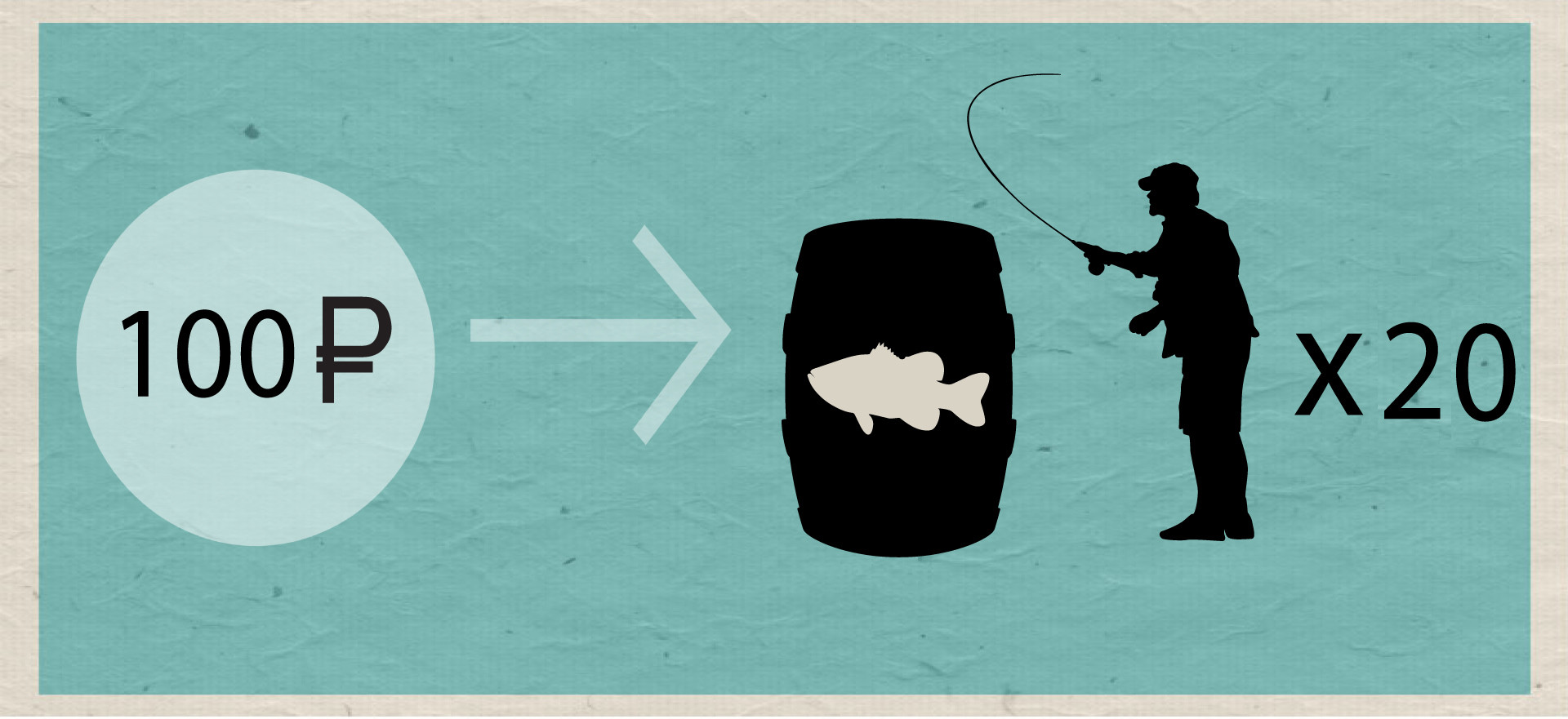

Copper ruble, 1662:

100 rubles = 20 barrels of sturgeon from the north or 4 expensive women's fur coats with gold and lace

Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, father of Peter I (the Great), tried to hold a monetary reform to finance the Russo-Polish war of 1654–1667. It was decided to take money “on credit from the people” and to issue copper equivalents, which could be exchanged back for silver rubles in the future. The salaries of civil servants (state employees) and archers were paid in copper, and taxes were collected in silver. Due to the fact that copper was easily forged, the value of the new money decreased by seven times in two years, resulting in the so-called Copper Riot of 1662, an uprising in Moscow that involved up to 10,000 Muscovites, mostly soldiers, archers and peasants. The revolt was suppressed, and copper coins were removed from circulation. However, only Peter the Great was able to finally stabilize the ruble, almost 40 years later.

Paper ruble - 1769

100 rubles = $72 (in 1792) = 10 cottages (Russian log houses, or ‘izbi’)

By the middle of the 18th century, when Europe already had an extensive network of banking and cash settlement using paper banknotes, Russians were still making payments solely in coins made from precious metals, production of which was costly to the state. Empress Catherine II (the Great) therefore decided to introduce the first paper money, ‘bank notes’ backed by the same silver rubles. However, Russia was not ready for this innovation. People did not want to keep their savings in banknotes and there was no trust in paper money. Moreover, each year thereafter the state increased banknote issues, regardless of their real value in silver. All these factors were to lead a severe financial crisis after Catherine’s death.

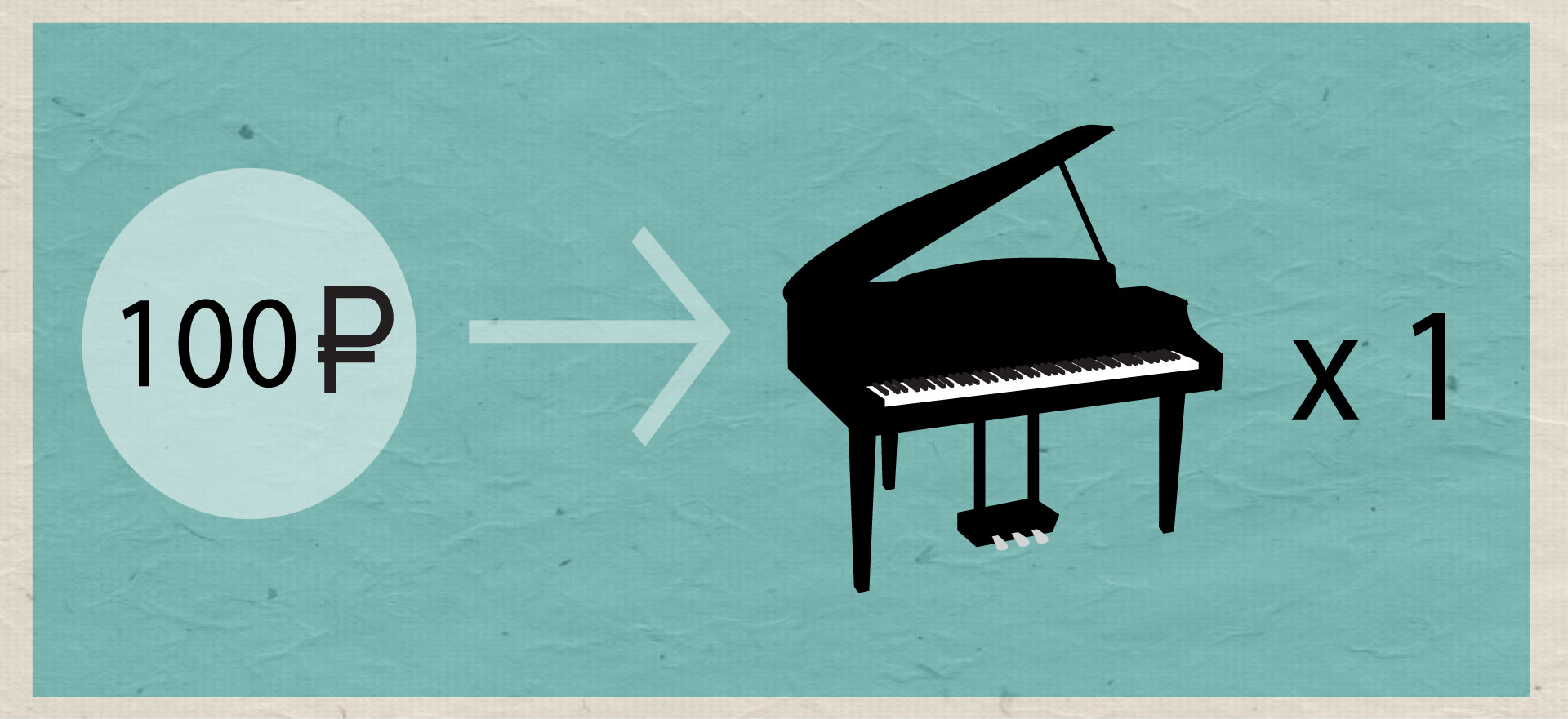

Golden ruble, 1895:

100 rubles = $51 = one carthorse, or a second-hand piano in pre-revolutionary Russia

One of the most successful monetary reforms in Russian history was held by finance minister Sergei Witte during the reign of the last Russian tsar, Nicholas II. Witte replaced the silver ruble with a golden one, putting an end to the devaluation of the banknotes issued under Catherine (some of which were still in circulation), as well as to currency speculation. The reform acted as a driver for the inflow of foreign capital into Russia and gave the country a hard convertible national currency.

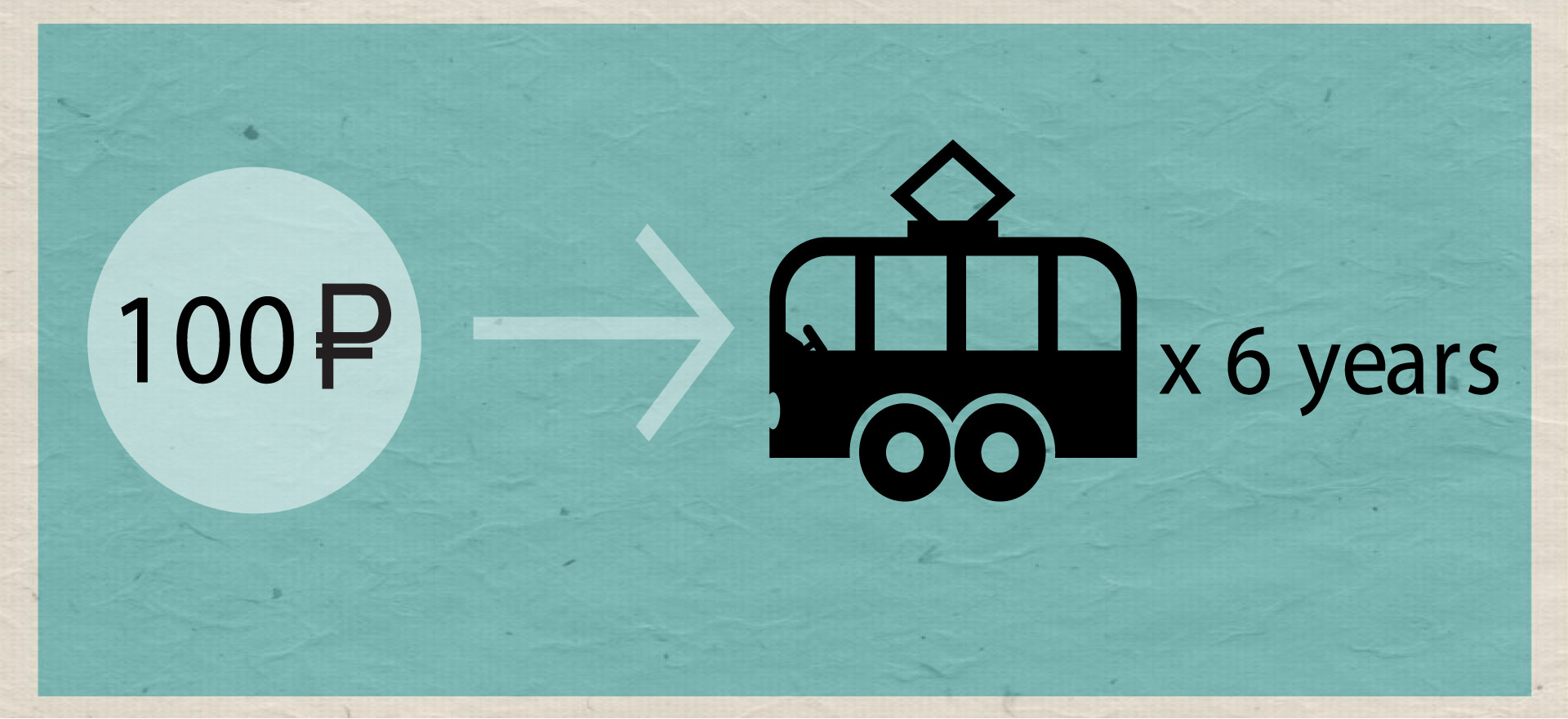

Soviet ruble, 1924:

100 rubles = $45 = 26 pairs of galoshes or 6 years of travel on the first Soviet tram

After the overthrow of the monarchy in 1917, civil war and the policy of "war communism" led to most severe hyperinflation in the history of the Russian currency. The ruble depreciated by more than 50 million times in the space of just five years. For example, in 1917, 100 rubles would buy $9, but by 1923 the same sum was worth only $0.00004. To stabilize the situation, in 1924 the USSR introduced a new Soviet currency backed by gold. The new hard ruble lasted just six years before the market rate of the ruble was canceled and money was replaced by cards for bread, meat and other essentials. During the entire Soviet period from 1917 to 1991, the card system was introduced four times - to deal with an acute shortage of food.

In the early 1920s the Soviet Union faced an unexpected challenge: Strictly opposed to the new communist regime, Western countries refused to accept payment for goods in the form of coins with Soviet symbols. To solve this problem, in 1925-1927 the government had gold coins minted bearing the image of Nicholas II. This allowed the Soviet government to purchase the necessary goods abroad using coins with the image of the deposed and executed tsar of Imperial Russia.

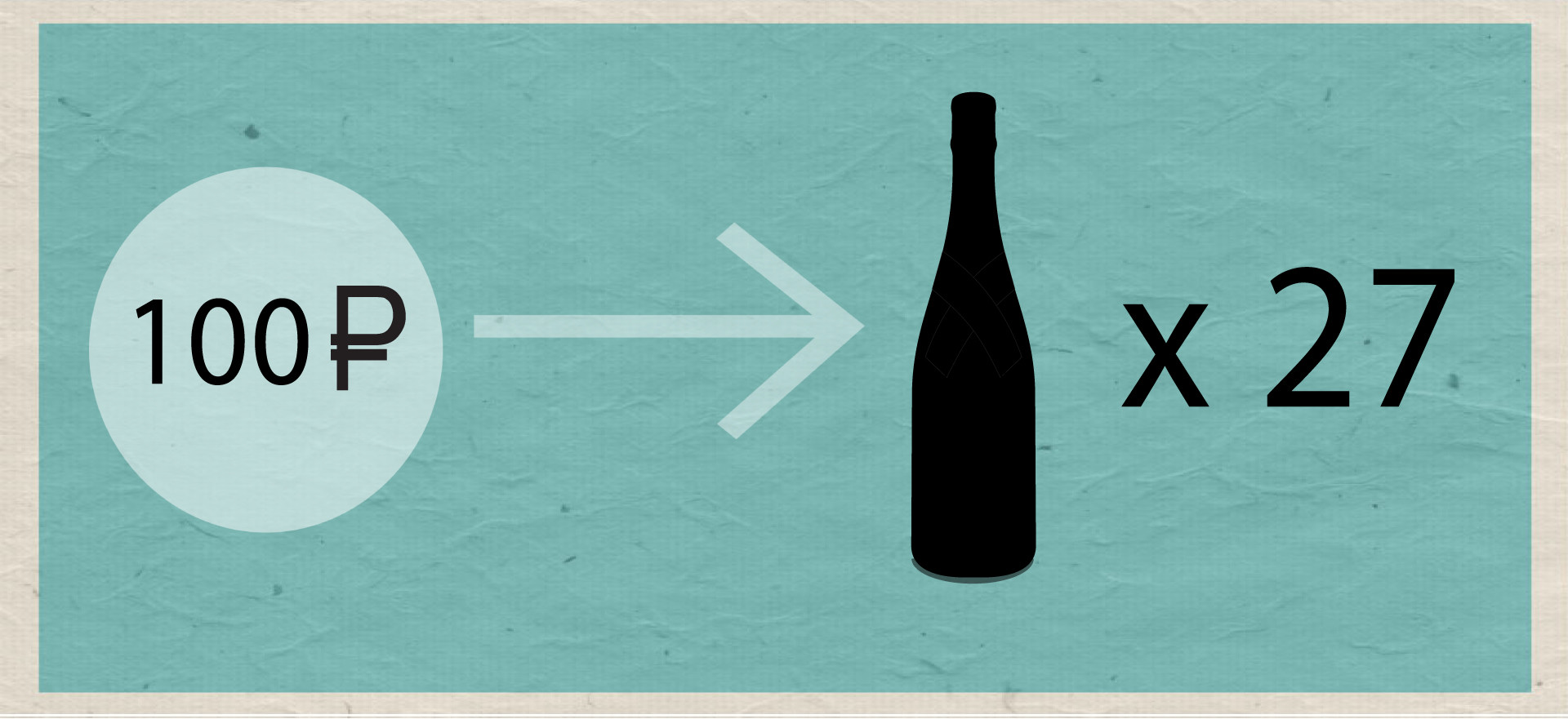

‘Oil’ ruble - 1970-1990s

100 rubles = $140 = 27 bottles of Soviet champagne or 1 pair of jeans (street value)

From 1931 onward, the Soviet ruble was solely a domestic currency for private use, and only the state had the right to exchange rubles for foreign currency and purchase goods from foreign countries. Due to the growth in world oil prices and increase in oil production from the mid-1970s on, the share of oil and other energy sources in the USSR’s total exports rose sharply, reaching a record 54 percent by 1985. The USSR economy had become oil-dependent, and this was to prove costly in 1985-1986, when falling oil prices struck the country’s foreign exchange earnings as well as the ruble. From 1990 onward, all foreign exchange earnings were aimed at covering the USSR’s foreign currency debt. At the same time the country’s ruble debt started to grow due to the budget deficit. All this played a role in the collapse of the USSR and led to the disastrous financial crisis in the new Russia. In the space of the following decade, the ruble experienced inflation and redenomination no fewer than four times.

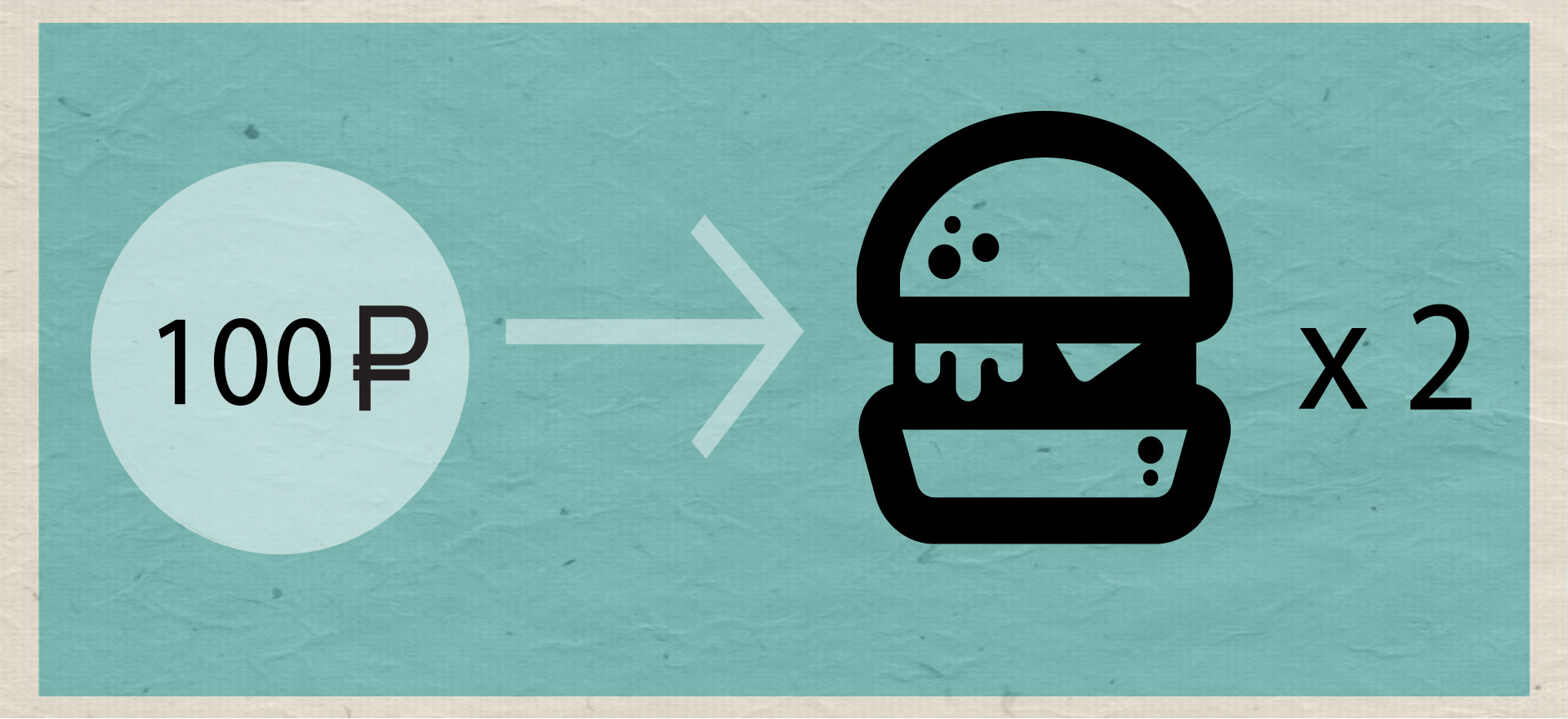

Putin’s ruble - 2000-2010s

100 rubles = $1.4 = a big bunch of bananas or 2 cheeseburgers at McDonald’s (as of May 2020)

In the 21st century, the Russian national currency hasn’t been a subject to significant reforms. Yet, it couldn’t avoid sudden fluctuations due to sudden crises. From the beginning of the 2000s, and until 2014, Russians were used to buying a U.S. dollar for not more than 35 rubles, but with the Russia-Ukraine crisis and a sharp decrease in global oil prices everything started to change. With a sharp devaluation in December 2014, the Russian currency never managed to reach its pre-2014 levels and, despite occasional rebounds, got used to the new norm - 50-60 rubles per U.S. dollar. This year, the situation continued to get even worse. After Russia walked away from OPEC+ talks, oil prices collapsed — and with them the ruble. As of May 2020, the Russian national currency was trading at around 73 rubles per U.S. dollar.

This article is based on material from the Russian State Archives of Economics and data from free sources.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox