Russia now has a black market for COVID vaccination certificates - here’s how it works

“We are one of the most influential labs in Russia. We issue antibody certificates, as well as COVID-19 vaccination certificates. We register the certificate on Gosuslugi (the official government website for payments, bills, taxes, appointments, etc.), which can be verified with no issue,” a man who went by ‘Dmitry’ explained. He actually found me on Instagram and became a follower. His own account looks like he’s itching to get caught: the name is simply ‘Spravki’ (“certificates”), with a few posts with basic information on the coronavirus.

He offered me a certificate for 1,900 rubles (approx. $26) over the phone - something that is, according to him, “a very timely thing to do today”.

The number of registered COVID-19 cases in Russia have reportedly more than doubled from 9,500 to more than 20,000 a day in the period from June 1 to June 24, 2021. In late June, Moscow and a number of regions enacted new, relatively harsh security measures affecting those unvaccinated. The capital, together with 11 regions, are now compelling employees of cafes, restaurants, beauty salons, hotels, hospitals, public transportation and so on, to get vaccinated. Authorities have given their employers the official right to fire staff without pay, should they fail to comply.

An employee of the sanatorium checks the certificate of vaccination against CoVID-19 from a guest before checking into the room of the sanatorium "Oktyabrsky" in the Krasnodar Territory.

Artur Lebedev/SputnikFurthermore, from June 28, Moscow cafes and eateries are only allowing customers with vaccination certificates (QR codes) and those with demonstrable COVID-19 antibodies, who contracted the coronavirus in the last six months. The same rules apply in Moscow Region, but also include hotel guests. In Bashkortostan, beauty salons, fitness clubs, banyas, student dormitories and intercity busses are also off-limits to anyone without the aforementioned proof. Meanwhile, in Krasnodar Region, tourists without QR codes and negative PCR tests will no longer be able to stay in hotels from July 1.

As these new measures are being rolled out, Telegram and Instagram are beginning to teem with channels and pages offering fake vaccination certificates and QR codes that don’t require them to leave home and visit an outpatient hospital to obtain them. There are no guarantees that the QR codes will work, but some Russians still prefer to try and cheat the system.

Dubious certificates

In order to find these services, one doesn’t have to look too hard: a search phrase containing the words “Covid справки” normally does the trick. A certificate - or spravka - will take you all of 15 minutes, with the document then sent as a PDF, containing a ‘real’ QR code, registered with the Gosuslugi government website. An English translation is also available. Meanwhile, orders of three or more get a 15 percent discount. Prices vary from 2,500 to 20,000 rubles (approx. $34-$276). The Instagram posts usually contain links to messenger profiles - all of them without phone numbers, names or any other information.

While chatting, the seller asks for your full name, date of birth, address and passport number. In just 15 minutes, you get a photo of a completed, watermarked form. The watermark is removed once the buyer transfers the required sum of money.

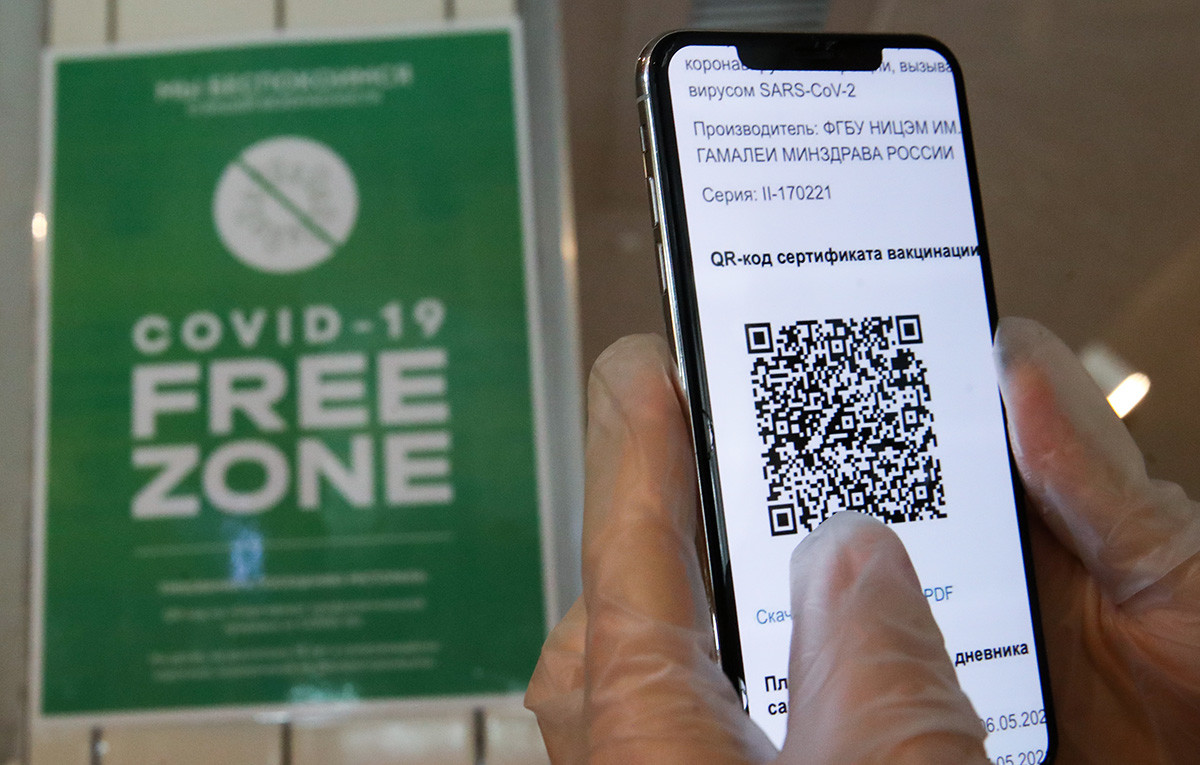

A person holds a mobile phone showing a QR code is seen at a 'COVID-19 free zone' sign at the entrance to the Mama Budet Rada restaurant for vaccinated customers in central Moscow.

Vyacheslav Prokofyev/TASSSo as to allay my fears, the person I was talking to sent me a screenshot of another Telegram channel, appearing to contain positive feedback from many happy clients - none of which can be found or contacted: “This could harm ours and their security. If you are not convinced, we can also offer a 50/50 deal - you transfer the second half after seeing proof of registration on Gosuslugi. We’ll specify that you’ve had your first shot at the Municipal Outpatient Hospital No. 5, and your second shot - at No. 220, we have partners there,” I was told by one of the anonymous sellers.

Instagram accounts offering certificates operate in the same way. The man calling himself ‘Dmitry’, however, contacted me by phone and claimed to be a specialist with a medical lab in Moscow’s Kolomensky district. According to him, staff at the lab personally complete the certificates for each person and enter the information into the registry. He then sends me the payment information - the clinic’s address, account number and so on.

The address appears to be correct, however, the individual tax number (normally included in Russia) belongs to a ‘Denis Evdokimenko’. If the RusProfile contractor database is to be trusted, Evdokimenko registered as an entrepreneur in the food business in September, 2020. The name and number also match up. Here’s where it gets interesting: the Getcontact app (which tells you what a person’s name is listed as in other people’s mobile contacts) paints a completely different picture: people list him as “Denis crypto”, “Investment fraudster”, “money fraudster” and “cheats retired people out of money”.

A woman with a vaccination status certificate uses a mobile phone outside a COVID-19 vaccination site at the TsUM Department Store in central Moscow.

Mikhail Tereshchenko/TASSThe moment I asked ‘Dmitry’ who this Denis Evdokimenko was, he blocked me.

Furthermore, according to Lenta.ru, certificates are also sold on the darknet, in the same room where you find illegal drugs - although the web portal claims that those certificates won’t pass any security checks.

‘I don’t want to risk my health’

According to Russians I’ve spoken to, who have managed to obtain a certificate, it’s indeed possible to find an honest seller - mainly through friends who have friends working in clinics and outpatient hospitals.

“I searched for a month for people that actually work in one of the Moscow labs and produce certificates. An acquaintance gave me a number,” says Marina (name changed at her request). “My personal data was almost immediately uploaded to the government portal and I paid 10,000 for the certificate. In any case, they’ve stopped doing it, as they had cameras installed on 24 June,” the 25-year-old told me.

A medical worker fills up a certificate of vaccination at a multifunctional center for the provision of state and municipal services in Moscow, Russia.

Alexey Kudenko/SputnikAccording to Marina, she bought the certificate out of fear of what a new and largely untested vaccine could entail for her health.

“I have this syndrome, it’s to do with my liver. It’s a rare condition, I don’t know how it will react to the vaccine - my doctor also has no clue. I don’t want to risk it simply because the government ordered it,” she says.

Another buyer from Moscow Region, Margarita, bought a certificate from one of the Moscow labs for 1,500 rubles.

“I don’t trust in the quality of our vaccines… I bought the certificate through an acquaintance that works at the clinic. I haven’t received it yet, it should arrive today or tomorrow. But the information about the first shot has already been uploaded to the website - I expect the same to happen after my second shot in two weeks,” Margarita says.

A man wearing a face mask shows a QR code for verifying his COVID-19 status at the entrance of the Euro 2020 fan zone in Luzhniki, in Moscow, Russia.

Pavel Bednyakov/SputnikSergey, a fitness trainer from Moscow (name changed on request) likewise confirmed that he purchased a certificate, but declined to comment further.

“Because of journalists like you, this market will soon be closed,” he added.

The first criminal charges

As of June 18, some 24 criminal investigations have been started in Moscow alone, according to ‘Rossiyskaya Gazeta’ newspaper, citing the police.

Duma Chairman Vyatcheslav Volodin also warned of the dangers of buying a fake certificate on his Telegram channel.

“It’s the vaccine that protects - not a fake note. Slippery ‘entrepreneurs’, wishing to make a quick buck on the pandemic, will face punishment… It’s glaringly obvious: we need to harshly prevent the illegal business of selling fake medical certificates. The responsibility lies with law enforcement. But it’s everyone’s duty to not purchase them either,” Volodin wrote.

A waitress and a customer at Chaikhona No 1 restaurant that has joined an experiment to create a COVID-19 free space in Moscow.

Alexander Shcherbak/TASSHe added that accountability for selling the fake notes rests with both the sellers and buyers of the notes, who risk infecting other people. Lawyer Yury Kapshtyk explained that counterfeiting certificates can result in both administrative and criminal charges.

“Article 327 of the Russian Criminal Code, pertaining to the falsification of COVID-19 vaccination documents, may lead to a limit on freedom, lasting up to two years, a prison sentence of six months, or one lasting up to two eyars,” Kapshtyk said.

Buyers caught with counterfeit documents also risk either their freedom being limited, or receiving a prison sentence of up to one year.

Article 19.23 of the Administrative Code, meanwhile, entails a fine of 30-50,000 rubles (approx. $415-$690) for “falsifying documents, stamps or forms and their use or sale.”

A woman receives a certificate after a COVID-19 vaccine injection at a Healthy Moscow pavilion in the Muzeon Art Park. The facility offers injections of the Gam-COVID-Vac (Sputnik V) and Vector's EpiVacCorona vaccines.

Anton Novoderezhkin/TASSShould the owner of a fake certificate or not contract the virus or somehow lead to others getting it, punishment could be much more severe, the lawyer adds: “The fine could be anywhere from 500-700,000 rubles (approx. $6,900-$9,600) or a sentence of up to two years. If at least one person dies as a result, the sentence could be two to four years; if more die - five to seven years,” Kapshtyk said in conclusion.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox