"...On the eve of the October Revolution, Lenin said: 'We'll face death unless we catch up with, and overtake, the advanced capitalist countries'. We are 50 to 100 years behind the advanced countries. We must traverse this distance in 10 years. Either we do it, or they will crush us." These were the words of Joseph Stalin that he proclaimed at the First All-Union Conference of Leading Personnel of Socialist Industry in 1931.

The nascent Soviet state arose from the ashes of the Russian Empire that was destroyed by a world war, two revolutions and finally, a bloody civil war that lasted almost four years. By 1922, Russian state coffers had been exhausted, and even worse large amounts of territory had been lost to nations that gained their independence, such as Finland and Poland.

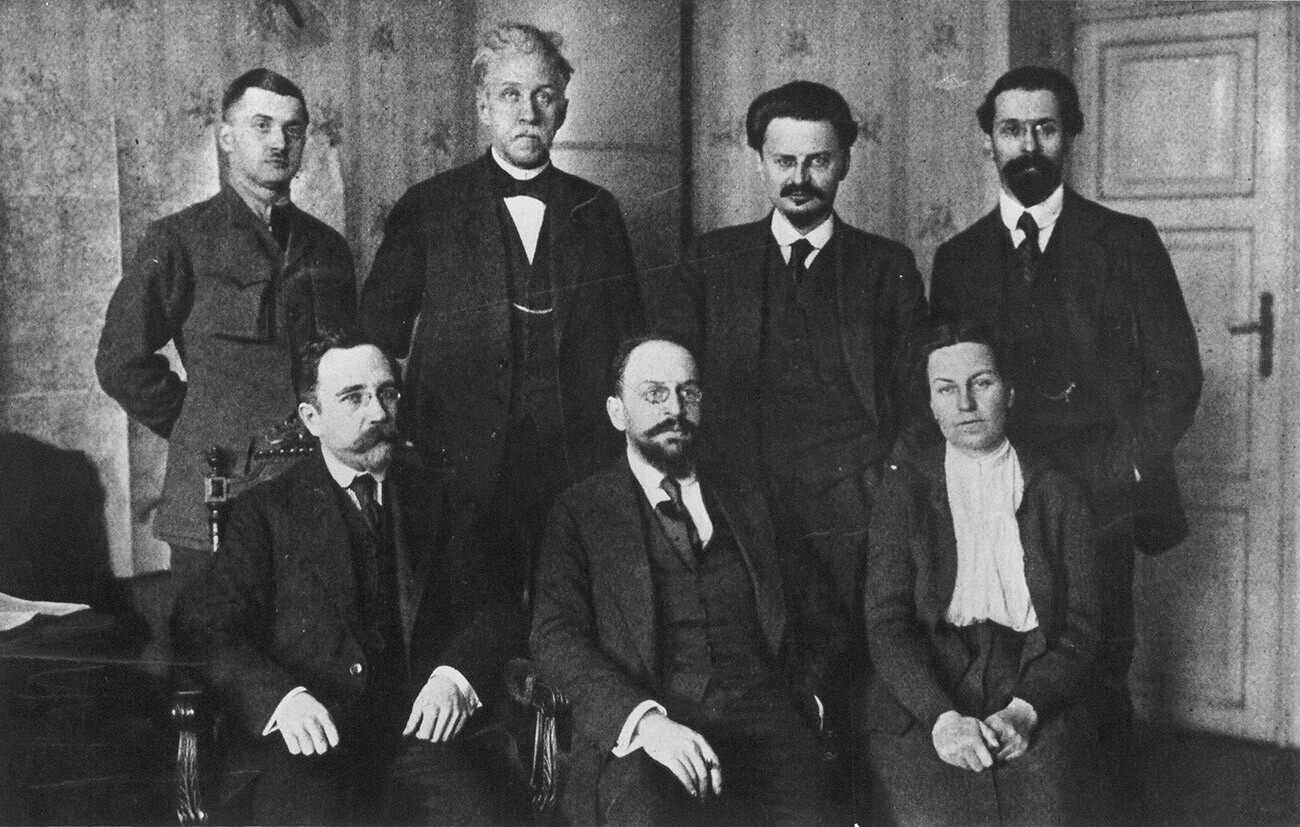

The Soviet delegation to Brest-Litovsk

Public domainThe Russian Empire in fact was relatively industrialized, ranking fifth in the world in terms of manufacturing production capacity, with 5.5% of the global total in 1913. However, Russia was far behind the U.S. (36%); Great Britain (16%); and Germany (14%). France was No. 4 at 6.4%.

The countries mentioned above were significant rivals to the Soviet Union and also posed potential threats to national security. Consequently, there was a sense of urgency to keep pace with them. Out of fear of aggression from the West, Stalin believed it was crucial to industrialize the USSR rapidly, and to do so using the country's own internal resources.

The Kremlin believed that the sale abroad of raw materials and agricultural produce would provide the USSR with the necessary funds required for industrial development. In 1929, however, a global economic crisis hit - the Great Depression - and the price of Soviet exports plummeted, depriving Moscow of desperately needed hard currency.

German and Soviet soldiers exchanging goods (February 1918)

Public domainMoscow's expectations failed to materialize and the USSR was forced to turn to western countries for financing. Germany became the main creditor, and as early as 1925 Berlin had provided Moscow with 100 million marks. The following year that amount increased threefold, and over the next nine years the official Soviet debt reached 900 million marks.

"...I am a metalworker by profession, I am 32 years old, married with one child, and have good professional references. In view of the fact that the situation of workers in Saxony is very difficult, I would like to emigrate to Russia since I am a member of the Communist Party. <…> K. Matuszak, Leipzig, 1923." This letter, addressed to the Soviet Chamber of Commerce, was written by one of the many Germans who wished to seek their fortune in the USSR. By the early 1930s there were even more such requests from foreign workers.

Those foreigners seeking economic opportunity in the Soviet Union were from very diverse backgrounds, both highly qualified specialists and ordinary workers, according to Russian historian Vera Pavlova. Some were inspired to move to the USSR due to their political views and a desire to help build Communism.

Workers at the Red Triangle factory listen to a lecture on the industrialization of the country

State Museum of Political History of Russia/russiainphoto.ruIn other cases, it was due to a desire for political asylum; while others were trying to escape the economic poverty and lack of opportunity in the West. The Great Depression gripped Europe and America at this time, bringing a wave of unemployment and despair.

In turn, Soviet factories had their own demands and needs to be met. The USSR, which had been forged amid the upheavals of the Revolution and Civil War (1918-1923), was very much short of labor.

Certain difficulties arose during the Soviet collaboration with foreign specialists (inspetsy, as they came to be known - which is abbreviated in the Soviet style from the Russian inostrannyye spetsialisty). In some cases, foreign specialists were sent to do things that they were not qualified for and knew nothing about.

German miners in a canteen, 1920s

SputnikIn turn, foreigners complained about poor working conditions, low-quality tools and a lack of interest in their initiatives and suggestions. Labor conditions at Soviet factories often lagged behind European standards. Furthermore, the language barrier, and sometimes separation from loved ones, negatively impacted the morale of foreign workers.

For their part, locals sometimes complained that their new colleagues were poor workers and enjoyed excessive and undeserved privileges. "The Germans won’t be working but will be ripping off the Russians because they’ll be paid 10 rubles in gold"; and "...they used to laugh at the Russians, calling them pigs, and now they have come to our country". These are some of the workers' complaints that were cited by Vera Pavlova in the course of her research.

The popular image of a foreign specialist recruited from abroad to work with local colleagues was even memorialized in Soviet literature. In their hilarious comic novel, The Little Golden Calf, satirists Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov described a German engineer by the name of Heinrich Maria Zauze who came to the USSR to work for the Soviet company Gerkules, and was totally bewildered by the local mentality and pace of life. "Dear Poppet, I am leading a weird and uncustomary life. I do absolutely nothing, but get my money punctually as specified in my contract," an astonished Herr Zauze wrote to his fiancée at home.

A still from "The Little Golden Calf" TV series showing the German engineer Heinrich Maria Zauze

Ulyana Shilkina/Park Production, 2005"Why did we recruit German workers? We spent a lot of money on them, we gave them more privileges, but we've got nothing in return. At meetings we were told that collaboration with German workers would mean an increase in worker efficiency, but in fact it turned out that they only hold up the fulfillment of the industrial-financial plan with their dillydallying at work and shoddy performance on the job," complained the workers of Factory № 50 named in honor of M.V. Frunze.

While there were some negative experiences, such as mentioned above, for the most part the skilled German workers gradually were integrated into production processes and in some places they even started to surpass their colleagues in efficiency.

The need to bring in foreign workers was also decided by the fact that the USSR imported equipment from abroad. Consequently, foreign specialists were needed who knew how to operate the equipment and to teach their Soviet counterparts to do so. These sales of equipment were often part of a larger project, such as the construction of an entire factory. Foreign firms would design the project, select the equipment, and transfer the patents and technical know-how to the Soviet side, while the USSR covered the costs and paid fees.

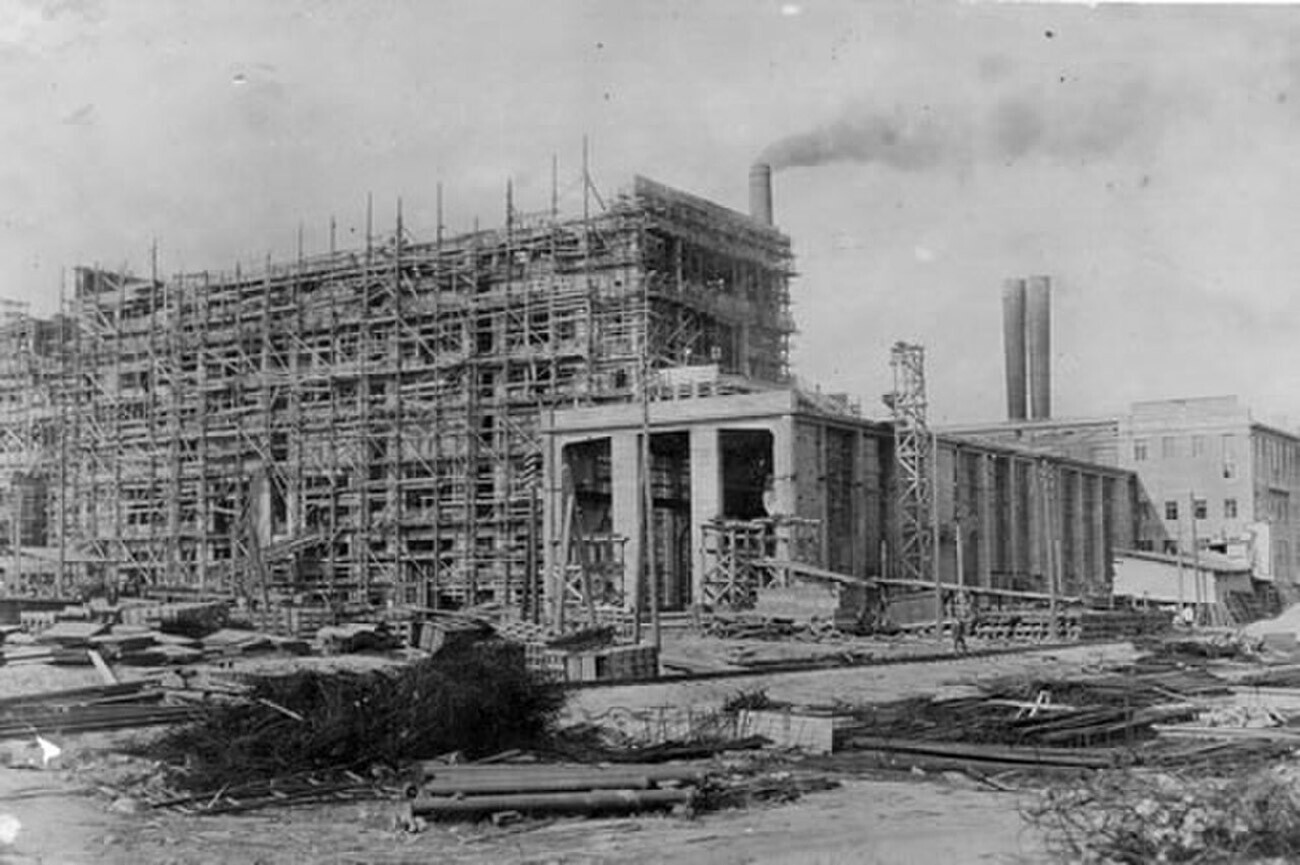

Construction of Kashira Power Plant headquarter

Public domainAccording to research by historian Boris Shpotov, of the 170 agreements on foreign technical assistance that were signed by the USSR between 1923 and 1933, German companies accounted for 73 deals, which is 43 percent of the total. In turn, Germany had a 47 percent share of Soviet imports in 1932.

Germany’s engineering behemoth, Siemens, was one of the USSR's major partners. In fact, it had been active in Russia during the imperial era. In the 1930s, during the period of rapid industrialization, Siemens was involved in a number of major projects; for example, it participated in construction of a power station on the Kura River in the Transcaucasus, and in the planning and site preparation for the Dnieper hydroelectric power station, as well as supplying turbines for the Kashira coal-fired power plant.

Lenin Square in Stalingrad, 1937

SputnikBuilding the Soviet utopia was more than just new industrial projects. An important part of Soviet industrialization was the establishment of so-called "socialist cities" (sotsgorod in Russian) that were centered around major industrial plants and specially designed to provide for all the needs of factory workers. A number of western architects and urban planners were invited to the Soviet Union for this purpose. Among them was Germany's Ernst May, who had made a name for himself designing many important buildings in Frankfurt am Main during the Weimar Republic.

In 1930, May came to the USSR with his team of 17 top specialists in urban planning, architecture, interior design, and art. In a short space of time the "May Brigade", which was inspired by Germany’s Bauhaus aesthetic, planned the development of 20 towns, including Magnitogorsk, Nizhny Tagil, Avtostroi (outside Gorky/Nizhny Novgorod) and Stalingrad. "We were responsible for the area between Novosibirsk and Kuznetsk, the giant Siberian coal basin. Right on the spot, we drew up detailed plans for six towns, a large proportion of which will already be built this year," a colleague of May's wrote in 1931.

German architect Ernst May

Otto SchwerinThese ambitious projects, however, yielded few results. From the very start they were planned as fairly low-cost projects, but Soviet authorities tried to save money on construction costs and they further cut the budget. Residents were allotted tiny residential spaces in low-quality housing with practically no amenities. Despite May's initial eagerness to serve the Soviet authorities, relations soon deteriorated as he became disillusioned with the country, and after three years May and many in his team decided to leave.

When the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933, Moscow’s cooperation with Berlin became difficult. The first Soviet five-year plan (1928-1932) - the very first effort at industrialization in a five-year time-frame - had just been completed. The country made an enormous leap forward, and in Stalin's words, the heavy industry plan had been fulfilled to the tune of 108 percent.

Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works

Southern Urals State historical museum/russiainphoto.ruRapid industrialization yielded positive fruits, and dependence on Western countries was much less than before. However, the second five-year plan (1933-1937) proved less successful, and the third one (1938-1942) was interrupted by the start of World War II, which obviously put an end to all cooperation with Germany.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox