What do Russian and Old Slavonic have in common?

Judging by how often online users engage in discussing the complexities, subtleties and the future fate of the Russian language, the latter presents quite a lively interest for its speakers. Sometimes, there are quite heated debates about its history, as well. At the same time, not all participants in these discussions have the relevant education or remember what they were taught in Russian lessons at school, so there is often some confusion in concepts and terms. Most people have heard of the ‘Old Slavonic’ language and since it is “old” and “Slavonic” (like Russian itself), they assume that it must be the direct ancestor of the “great and mighty” Russian language. There are also those who believe that Old Slavonic is the language of church books that are used in church services to this day. Let’s find out what the real relationship between Russian and Old Slavonic is.

Myth 1: In ancient times, Slavs spoke Old Slavonic

It is believed that Slavs’ forebears came to Europe in the 2nd century BC, presumably from Asia. This theory is confirmed by a comparative analysis of modern Slavic languages and Proto-Indo-European, a reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family, comprising Slavic, Romance, Germanic, Iranian, Greek and other languages.

In the pre-literate era of their existence, Slavic tribes used the Proto-Slavic language, which was common to all Slavs. No manuscripts in it have survived (or been found), so it is believed that it had no script. It is difficult to talk with any certainty about what exactly that language was like (how it sounded, whether it had dialectal forms, what its vocabulary was, etc.), since all the available information about it has been derived by linguists through reconstruction based on a comparison of the existing Slavic and other Indo-European languages or came from testimonies of early medieval authors, who left descriptions of the life and language of the Slavs in Latin, Greek and Gothic.

In the 6th-7th centuries AD, the Proto-Slavic community and its language was already more or less distinctly divided into three dialect groups (eastern, western and southern), within which the modern Slavic languages formed over a long time.

Thus, ancient Slavs in the pre-literate era did not speak Old Slavonic, but rather dialects of the Proto-Slavic language.

So where did it come from?

Ancient Slavs were pagans, but under the influence of historical and political circumstances, starting from the 7th century (primarily South and West Slavs - due to the geographical proximity and powerful influence of neighboring Byzantium and the Germanic kingdoms) gradually adopted Christianity. In effect, this process stretched over several centuries.

This created a need for an alphabet and a written language - first of all, for the dissemination of liturgical texts, as well as state documents (the adoption of a single faith, which united previously scattered pagan tribes, completed the process of the development of statehood by some of the Slavic peoples, a good example of which was Old Rus’).

To solve this problem, it was necessary to fulfill two conditions:

- to develop a system of graphic symbols for committing sounds into writing;

- to create a single written language that would be understandable to Slavs from different parts of Europe: at the time, speakers of all Slavic dialects could understand each other, despite the differences between their dialects. It was that written language that became Old Slavonic, the first literary language of the Slavs.

The birth of Slavic alphabet

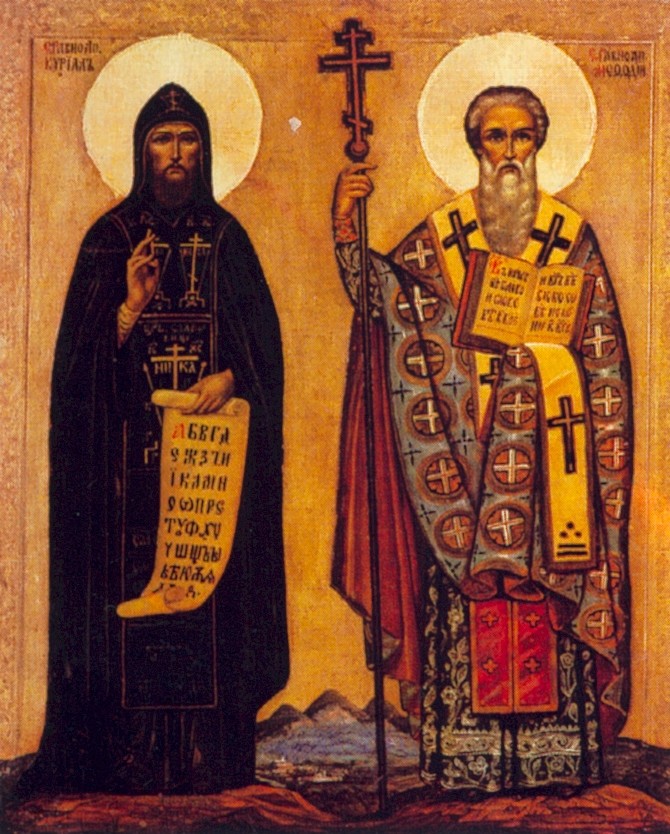

The task fell to the brothers Cyril and Methodius. They came from the city of Thessaloniki, which lay not far from the border between the Byzantine Empire and the Slavic lands. The Slavic dialect was widespread in the city and its environs and, according to historical documents, the two brothers were fluent in it.

Cyril and Methodius

Public domainThey were of noble birth and were extremely well-educated: the younger brother, Cyril (Constantine), had among his teachers the future Patriarch Photius I and Leo the Mathematician, who later, when teaching philosophy at the University of Constantinople, would become known as the ‘Philosopher’.

The elder brother, Methodius, served as a military leader in one of the regions populated by Slavs, where he became well acquainted with their way of life. He later became the head of the Polychron monastery, where he was soon joined by Constantine and his disciples.

The circle of people that formed at the monastery and was led by the brothers began to develop a Slavic alphabet and translate Greek liturgical books into the Slavic dialect.

It is believed that the idea to develop a Slavic script came to Cyril following a trip he had made in the 850s as a missionary baptizing the population living near the Bregalnica River. It was there he realized that, despite having adopted Christianity, these people would not be able to live according to the law of God, because they could not use church books.

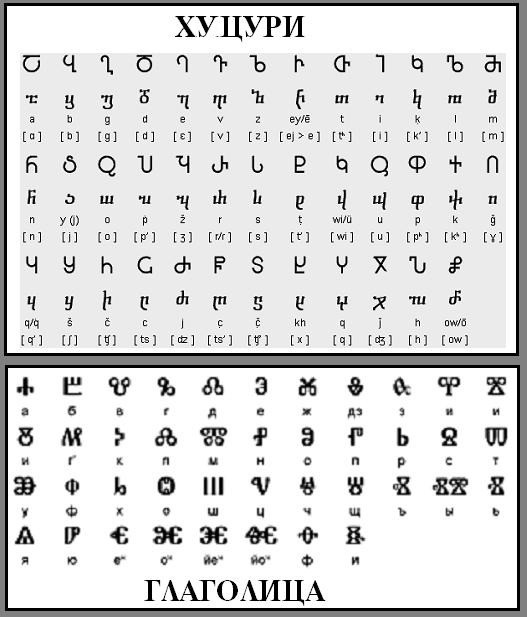

The first alphabet was Glagolitic

The first Slavic alphabet was Glagolitic (глаголица, from глаголить - “to speak”). While creating it, Cyril knew that the letters of the Latin and Greek alphabets could not accurately convey the sounds of Slavic speech. There are different theories as to its origin: some researchers argue that the Glagolitic script was based on a revised Greek script, others that the form of its symbols resembles the Georgian church script known as Khutsuri, which - hypothetically - Cyril could have been familiar with. There is also a theory, which has not been reliably confirmed, that the Glagolitic script was based on a certain runic script that Slavs had used in the pre-Christian era.

The Glagolitic and the Khutsuri scripts

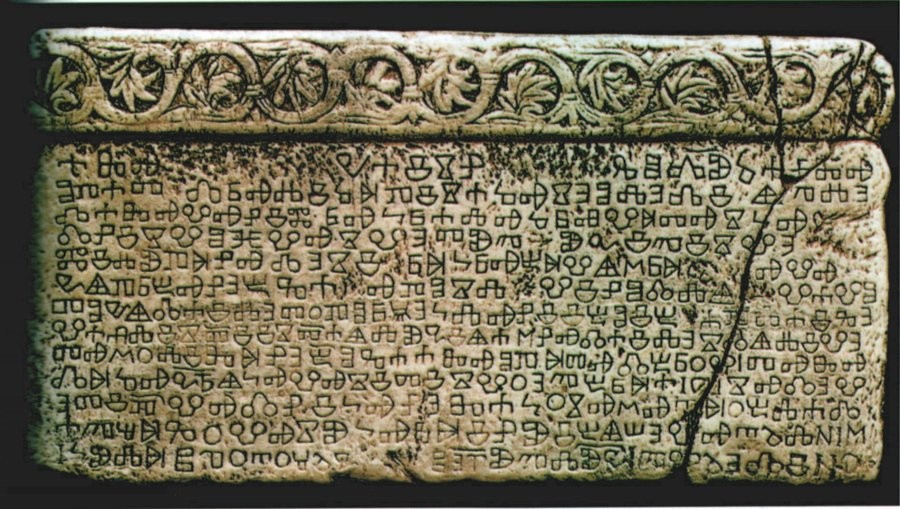

Public domainThe spread of the Glagolitic alphabet was uneven, both in terms of geography and duration of its use. It ended up being only widespread and long use on the territory of present-day Croatia: in the regions of Istria, Dalmatia, Kvarner and Međimurje. The best known Glagolitic manuscript is the Baska tablet, which was found in the town of Baška on the island of Krk and dates back to the 12th century.

Baška tablet

Public domainInterestingly, on some of the numerous Croatian islands, the Glagolitic script was in use until the beginning of the 20th century, while the city of Senj used it until the start of World War II! They say that, on some parts of the Adriatic coast, you can still come across very old people who know it still.

It should be noted that Croatia is proud of this historical fact and has elevated the ancient Slavic script to the rank of a national treasure. In 1976, a Glagolitic Alley was built in the Istrian region: it is a 6 km road lined with sculptures celebrating milestones in the development of the Glagolitic script.

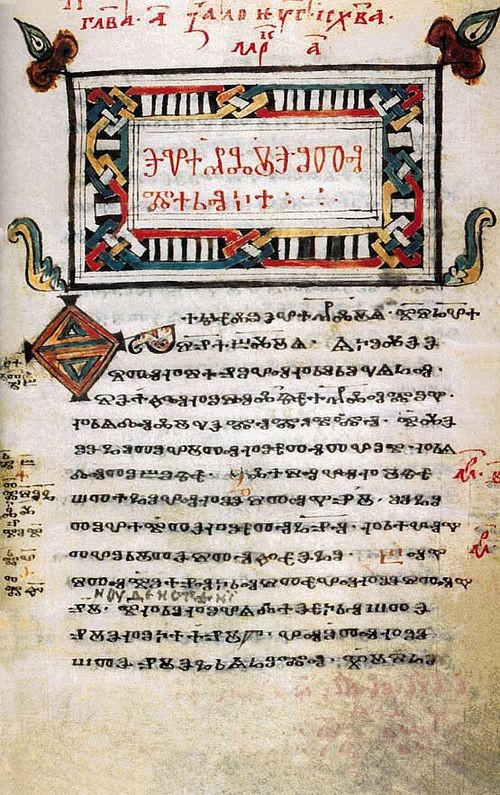

The Glagolitic script

Public domainWhereas in Russia, the Glagolitic script was never in widespread use (academics have discovered only a handful of inscriptions in it). That said, the Russian-speaking segment of the internet has several converters from Cyrillic into Glagolitic. For example, the phrase: “Glagolitic was Slavs’ first alphabet” will look like this:

Ⰳⰾⰰⰳⱁⰾⰻⱌⰰ - ⱂⰵⱃⰲⰰⱔ ⰰⰸⰱⱆⰽⰰ ⱄⰾⰰⰲⱔⱀ

Was Cyrillic the second script?

Despite the obvious origin of the name ‘Cyrillic’, Cyril was not the author of the alphabet we use to this day.

Most scholars are inclined to believe that the Cyrillic alphabet was developed after Cyril’s death by his pupils, in particular, Clement of Ohrid.

It has still not been established for certain why Cyrillic supplanted the Glagolitic alphabet. Some believe it happened because Glagolitic letters were too elaborate to write, while others are convinced that the choice in favor of the Cyrillic alphabet was made for political reasons. The fact is that, at the end of the 9th century, the major centers of Slavic writing moved to Bulgaria, where the disciples of Cyril and Methodius, expelled by the German clergy from Moravia, had settled. Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria, during whose reign the Cyrillic alphabet was created, was of the opinion that the Slavic script should be as close as possible to Greek.

‘The Bulgarian Tsar Simeon: The Morning Star of Slavonic Literature’, А. Mucha, 1923

Prague City GalleryMyth 2: Old Slavonic is a forerunner to Russian

The Old Slavonic language that Cyril and Methodius created and recorded in translations of books of the residents of Thessaloniki was based on South Slavic dialects, which was absolutely logical. At the time, the Russian language already existed, albeit, of course, not in its current form, but as the language of the Old Rus’ community (the eastern branch of Slavs, the ancestors of Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians), in fact, representing an assembly of Old Russian dialects. At the same time, it was not a literary language, but rather a natural living language, which, unlike Old Slavonic, served as a means for everyday communication.

Subsequently, when Old Slavonic began to be used in church services and books, inhabitants of Old Rus’ began to put down their spoken language in Cyrillic, thus starting the history of the Old Russian language (see, for example, the collection of Novgorod birch bark manuscripts, which Academician Andrei Zaliznyak spend decades studying). Thus, an educated person who lived in ancient Novgorod, Pskov, Kiev or Polotsk could read and write in Cyrillic in two closely related languages, South Old Slavonic and its native East Slavic dialect.

Myth 3: Present-day church services are conducted in Old Slavonic

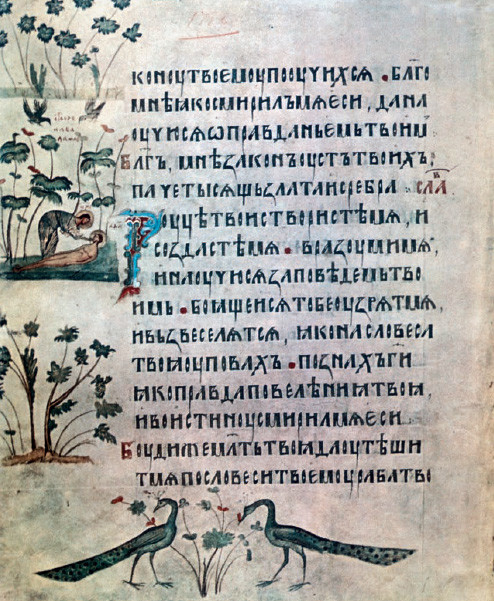

The Old Church Slavonic script

Public domainOf course, in olden days, that was the case. After all, Old Slavonic was created so that Slavs had the opportunity to listen to the liturgy in a language they could understand. However, over time, the language of church books underwent modification, gradually adopting the phonetic, spelling and morphological features of local spoken dialects under the influence of the human factor, i.e. translators and scribes. As a result, there emerged so-called versions (local variants) of that literary language, which, in fact, was a direct descendant of Old Slavonic. Slavicists believe that the classic Old Slavonic language ceased to exist in the late 10th - early 11th century and, starting from the 11th century, services in Orthodox churches have been conducted in local versions of Old Church Slavonic.

Currently, the most common of those local variants is the so-called ‘Synodal’ (“New Moscow”) version of Old Church Slavonic. It formed after the church reform of Patriarch Nikon in the mid-17th century and continues to be the official language of the Russian Orthodox Church and is also used by the Bulgarian and Serbian Orthodox churches.

What do modern Russian and Old Slavonic have in common?

The Old Slavonic language (and its “descendant”, Old Church Slavonic), having been the language of religious books and worship for more than a millennium, undoubtedly had a powerful South Slavic influence on the Russian language.

Many words of Old Slavic origin have become an integral part of modern Russian vocabulary, so much so that to an ordinary Russian speaker, there is no doubt that they are of Russian origin. Without delving into linguistic intricacies, suffice to say that even such simple words as сладкий (sweet), одежда (clothes), среда (Wednesday), праздник (holiday), страна (country), помощь (help), единый (single), to name a few, are, in fact, of Old Slavonic origin.

In addition, Old Slavonic has also influenced word formation in Russian: For example, all words with the prefix пре- or participles with the suffixes -ущ/-ющ, -ащ/-ящ have an element of Old Slavonic in them.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox