An English girl attended school in Russia. Here's what she had to say!

Winter days in a Russian school.

Personal arhive8:45 am on September 1, 2010. I stand timidly in a stifling school hall perfumed with the fragrance of dozens of elaborate flower bouquets and mothers’ eau de toilette. All around me stand my beaming, immaculately dressed peers and their parents; the mothers and daughters in extravagant dresses, hair adorned with white ribbons. For the boys and their fathers - suits, ties and shiny shoes (some even sporting tinted aviators and top hats…). Loud chatter, music and the sheer volume of plant life in the tiny hall makes for all-round confusion – that unapologetic, yet strangely appealing, semi-anarchy so typical of Russia.

Day of Knowledge in a Russian school.

Personal arhiveThis is back to school “Russian style”, something I was lucky enough to experience twice in the two years I spent living in Moscow with my family from 2010-12. The move from a quaint market in the South-East of England to the vast and overwhelming metropolis of Moscow opened my eyes to many stark cultural differences, one being the Russian attitude towards schooling and specifically how they marked the beginning of the school year.

In the UK, this is something we dread: the summer holidays come to an end, the September rain creeps in, the weeks leading up to the return to school are spent with parents panic buying P.E. socks and having arguing with their children about why they do not need a full set of rainbow-colored berry-scented erasers every year.

The extent of the Russian celebration of the first day of school - День Знаний (“Day of Knowledge”) - outdoes any attempt we in the UK make to see in the new academic season.

Day of Knowledge, September 1.

Personal archiveFor me, the Russians do something really beautiful and pick up on something which we blindly fail to notice back home – this day does not have to be a reluctant return to the mundanity of lessons and homework. It can, instead, be a celebration of knowledge, an observance, an appreciation for education and all it gives us. This day is one to honor tradition, to come together, to ground oneself and prepare one’s mind for the imminent year of learning.

I shuffle in my scratchy tights and boots, clutch my drooping bouquet, abashed.

At exactly 9:00 am, the school bell is rung to huge cheers and applause in a tradition known in Russian as Первый Звонок (“first bell”). Alumni and benefactors give speeches, the school anthem is sung and flowers are festooned upon teachers; and so, with an atmosphere of such festivity, the school year begins…

Забота – Typically Russian care

I attended school in Moscow from age 10 to 12 - the equivalent of years six and seven. In the UK, this is a time where a child is granted their first independence, whether this takes the form of walking to and from school on their own, taking responsibility for their own belongings or attempting their homework without assistance. Being the eldest of three and having already had the reins considerably loosened back home, it was quite shocking to experience the treatment of children my age in Russia.

The age-old national concept of забота (“care”) refers to the rigorous care and protection of children by older generations, to the point where it practically becomes their full-time job. In my time at school, забота came in many forms: stuffing us with food, wrapping us up tightly in winter clothing and reminding us that most things could in some way cause us to fall ill. Some behaviours I found just extraordinary - on a school summer camp in Greece, we were allowed in the sun for exactly ten minutes and the sea for exactly five, both of which were timed with a stopwatch. In the classroom, only boys were permitted to pick up and move any furniture around, as the girls were thought to be too weak and delicate. Girls and female teachers were also not permitted to sit on the floor for risk of infertility, or cross one leg over another when seated for risk of blood clots.

I now understand that these baffling behaviours, which I found, at times, to be frustrating, ludicrous and restrictive, are truly just evidence of the huge impact of Russia’s turbulent past on its social customs. Concerns around health, sickness and sufficient warmth and food stem from a time when millions died in the freezing Russian winters, famine was rife across the country and poor living conditions and lives of hard labor meant many fell sick or died young.

I arrived at my Russian school knowing very little of the language, which I now know to be full of beautiful complexity and nuance. Despite the disorientation and miscommunications that came from not understanding what was going on around me a lot of the time, I think I was more baffled by the behaviours of my peers and teachers, which I found so unfamiliar and intriguing.

Food, clothing and curriculum

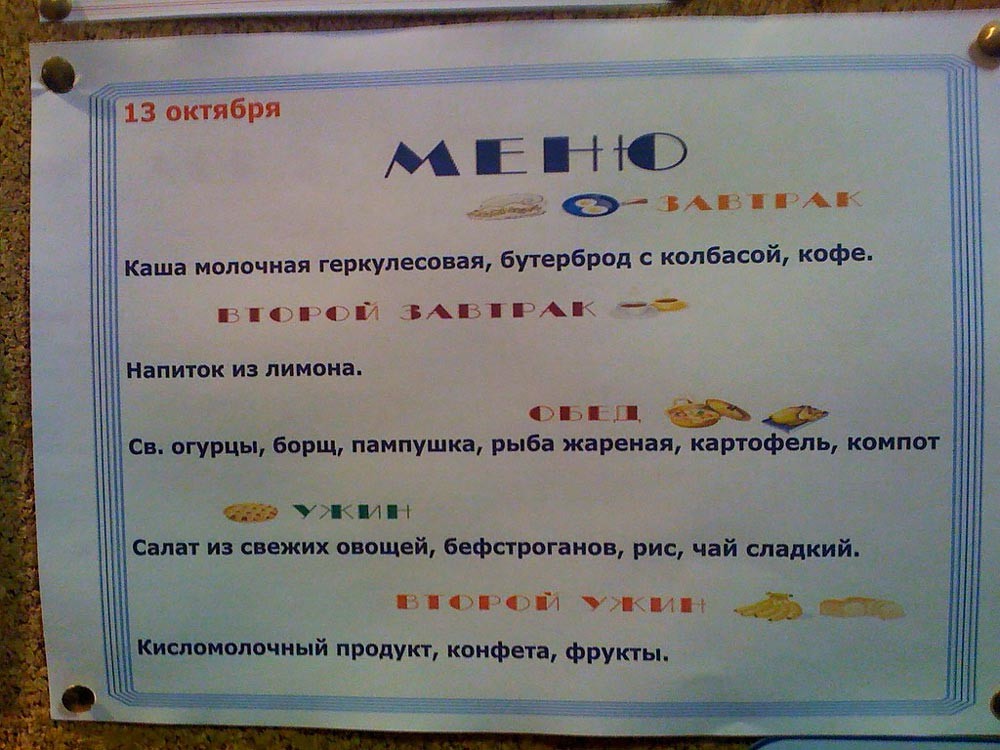

The menu at a school canteen.

Personal archiveNotable moments included food: my school, which was private, took it upon itself to feed us constantly – on arrival at 8 am we were given завтрак (“breakfast”) consisting of cheese, or salami on bread, каша (“porridge”) and mugs of very sweet, black tea. After the first lesson came the второй завтрак (“second breakfast”), which was much the same, although sometimes inexplicably included cheesy pasta. Lunch was three hours later and consisted of Russian classics – the obligatory супчик (“little soup”), котлеты (“meat cutlets”), пельмени (“meat-filled dumplings”) and сырники (“quark pancakes”) and more sweet tea. After lunch, we would гулять на улице (“walk outside”’, essentially recess), which was followed by a полдник (“half-day”; ie. a snack); typically, fruit, some kind of sweet cake and yet more sweet tea – it was no surprise we were all constantly hyperactive! Then came dinner at 5 pm, before two hours of after-school clubs.

Clothing was something to which I also had to adapt. We would spend at least 30 minutes of every day undressing on entry into the building and then redressing for our time spent outside, particularly in the winter months. All students had a pair of “indoor shoes”, which were kept at school – woe betide anybody who was found to be dirtying the indoors with their snowy “outdoor shoes”!

Russian values were also upheld, as far as the curriculum was concerned. Great emphasis was placed on learning things by heart, be it Pushkin’s poetry or a piano piece; the ability to recite or play from memory confirmed absolute knowledge and appreciation. I have vivid memories of receiving indignant slaps to the hand from piano teacher Elena, as I butchered the theme from Titanic. More successful was my by-heart rendition of Pushkin’s На лукоморье дуб зеленый (“Green Oak on the Seashore”), which won me a ‘4’ grade (the equivalent of a ‘B’). Whilst the immortalisation of great artists and their art was fundamental at school and, indeed, is in all Russia, creativity of the individual was hugely encouraged - I was involved in multiple personal and group projects in the spheres of film-making, photography and theater.

I became accustomed to a level of informality in our interactions with teachers; they would often scold us or attempt to reason or compromise with us, as though we were their own children and they were our carers rather than employed passers of knowledge. For me, this was one of the biggest differences between school in Moscow and school in the UK. Perhaps it was because we spent almost 11 hours a day at school, but I grew to love my teachers, as well as sometimes feeling deep frustration and anger towards them, when I thought there had been some injustice. I know my peers felt the same: as we shared a deep trust in our teachers and acted upon a mutual reliance on their consistent presence, to which they responded with near-maternal behaviours.

On returning to the UK and school there, I marvelled at the ease of everything, the simplicity of communication, the independence, the freedoms we had as a given. In some strange way, despite spending the past two years being treated as a child far younger than my age, I had grown up and matured far more than anyone else.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox