‘Worthy of the greatest glory’: How the U.S. saved millions of Russians from starvation

Vernon Kellogg, an American scientist and an ARA official, on a Moscow street, while on a humanitarian mission to Russia

Public DomainA disaster not seen since the Middle Ages

The famine that spurred the U.S. to send a huge humanitarian mission to Soviet Russia is considered one of the greatest European tragedies since the Black Death in the mid 15th century. As a result of World War I, the Civil War, and the Bolshevik’s coercive economic policies, many regions of Russia in 1921-1922 faced unprecedented starvation.

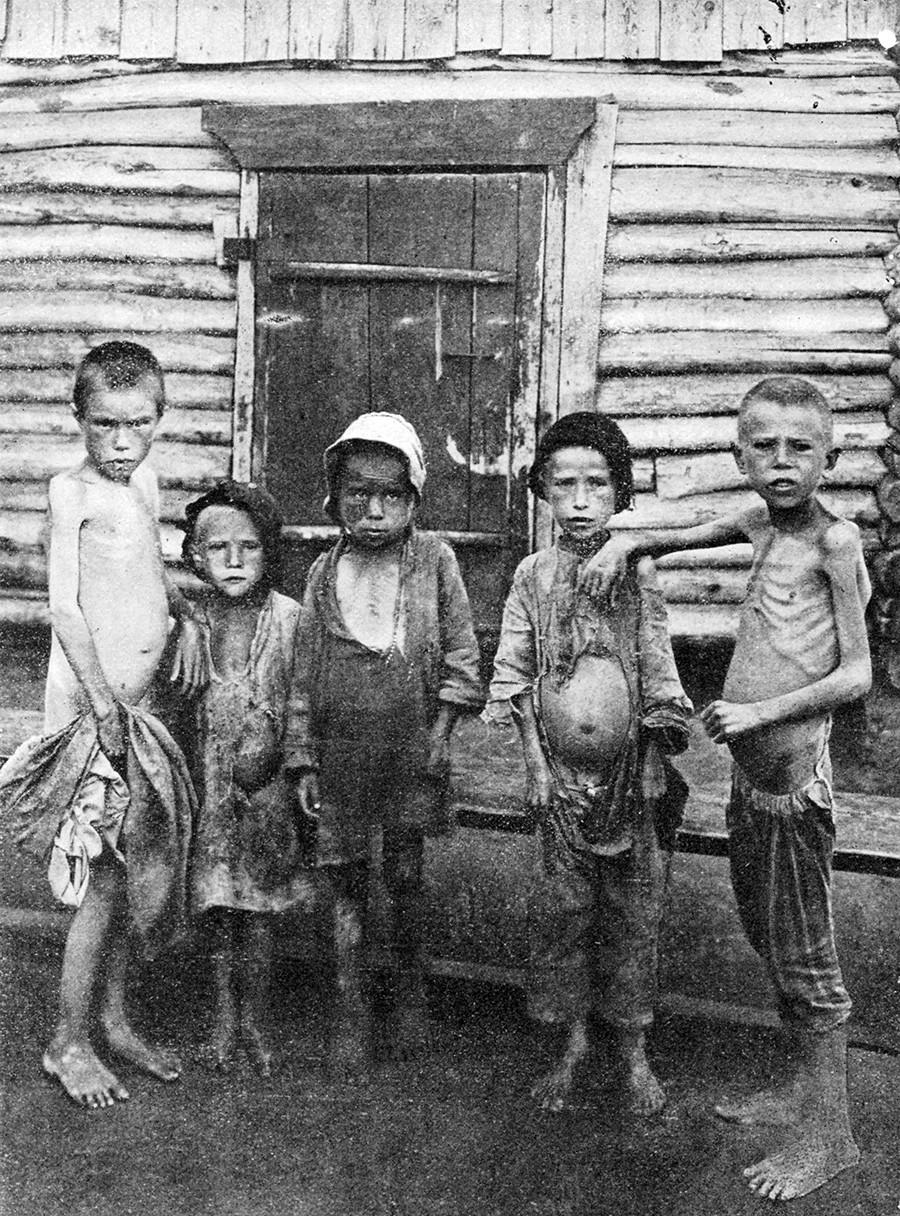

Tens of millions of people were affected, and it’s believed that no less than 5 million people died. This catastrophe forced the Soviet regime to ask for help from the “capitalist world.”

Fighting famine and ‘the disease of Bolshevism’

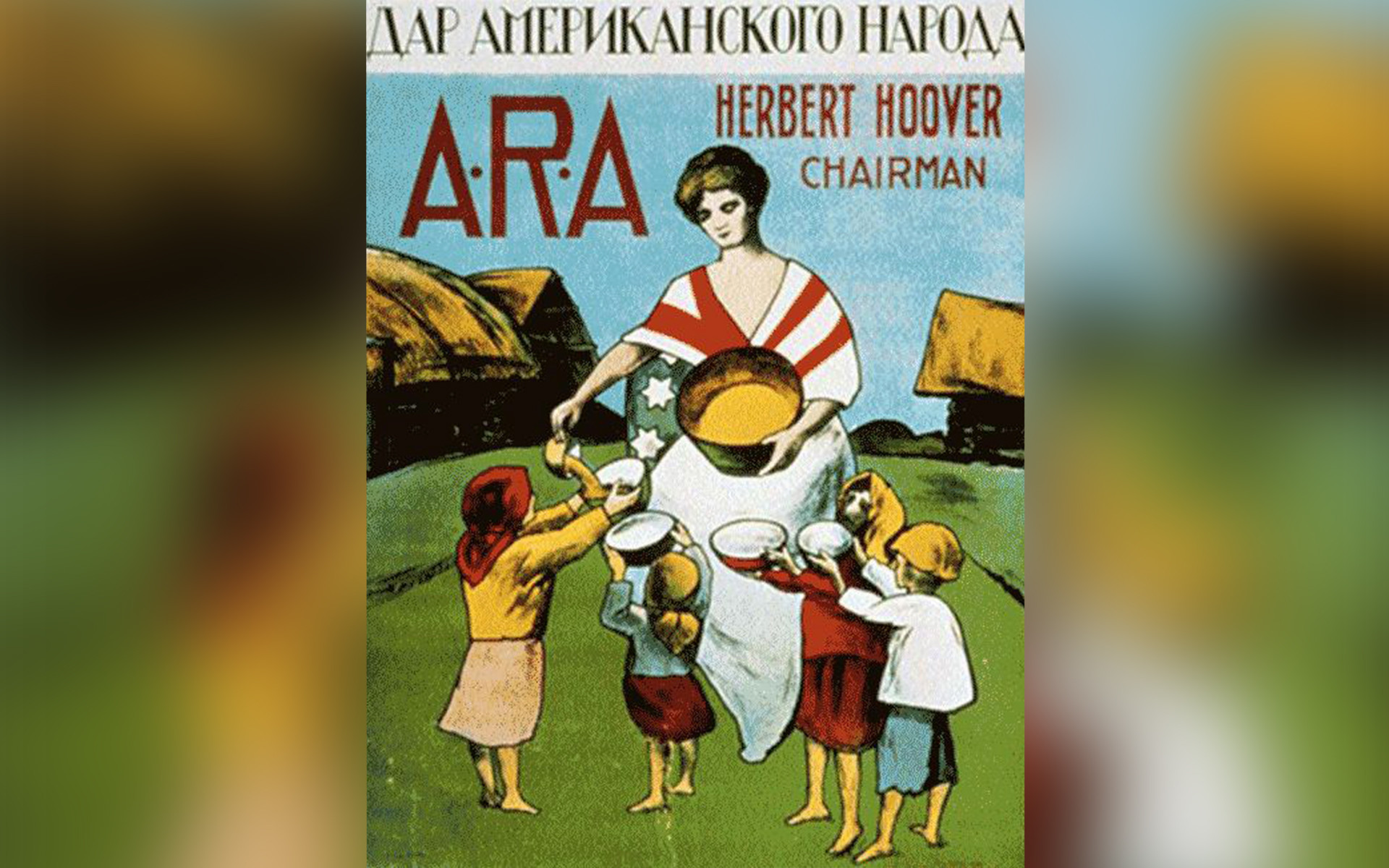

Meanwhile, in the U.S. in April 1919, two years before the devastating famine broke out in Russia, Congress passed the “European Famine Relief Bill,” earmarking $100 million to help European countries experiencing food shortages after World War I. The effort to fight the famine was led by the newly created American Relief Administration (ARA) headed by Herbert Hoover, a future president.

It is estimated that between 5 and 10 million people died because of the famine in Russia, many of them were children

Mary Evans Picture Library/Global Look PressSoviet Russia was not originally included on the list of countries to receive American help. At this time, the U.S. and other Western powers had intervened militarily in the Russian Civil War to support anti-Bolshevik forces in several regions.

In fact, the U.S. food program was aimed against Soviet Russia, as an effort to thwart leftist radicalism from spreading to European countries that faced worsening living standards. As historian Bertrand Patenaude put it, “The economic and political instability of those states, most of them newly created out of the ruins of the old empires, made them vulnerable to the contagion from the East of what was commonly called ‘the disease of Bolshevism.’ It was generally assumed by European and American statesmen that this malady was caused by hunger; Bolshevism was what happened when good people went hungry.”

Russian intellectuals and the Kremlin’s plea for help

The situation changed drastically by

"The gift of the American people," written on this ARA poster

Russian writer Maxim Gorky appealed to the international public, asking for help. Next, Lenin also appealed for help to the international proletariat. In September, the famous Norwegian explorer,

Soon after, a deal was reached between the ARA and the Soviet government. It would be a mistake, however, to think that by helping the Soviets the political agenda pursued by Hoover had been abandoned.

“Hoover believed that if he could only relieve the Russians’ hunger, they [Russians] would return to their senses and recover the physical strength to throw off their Bolshevik oppressors,” Patenaude argues.

Feeding 10 million people per day

In the end, Hoover did not achieve his political goal. To the contrary, by saving millions of lives he helped stabilize the situation in Russia, thus contributing to the Bolshevik’s legitimization in the minds of the Russian people.

A usual menu at ARA kitchens included corn grits, condensed milk, cocoa, white bread and sugar – all of which were imported

SputnikThe situation was indeed drastic. As

She also cited the terrifying recollections of one of the ARA workers in Russia: “I have seen piles of corpses half naked and frozen into the most grotesque positions with signs of having been preyed upon by wandering dogs. I have seen these bodies – and it is a sight that I can never forget.”

"America - to starving Russia", says another ARA poster

Soviet authorities opened 7,000 kitchens to feed those in need, but it was far from enough. But by August 1921, the ARA established as many as 19,000 kitchens, feeding 10 million people every day. A usual menu had corn grits, condensed milk, cocoa, white bread

“Your help will enter history as a unique, gigantic achievement, worthy of the greatest glory, which will long remain in the memory of millions of Russians whom you have saved from death,” Maxim Gorky wrote to Herbert Hoover, praising his help.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox