Russia paid hundreds of millions of Tsarist-era debts but it’s not enough. Why?

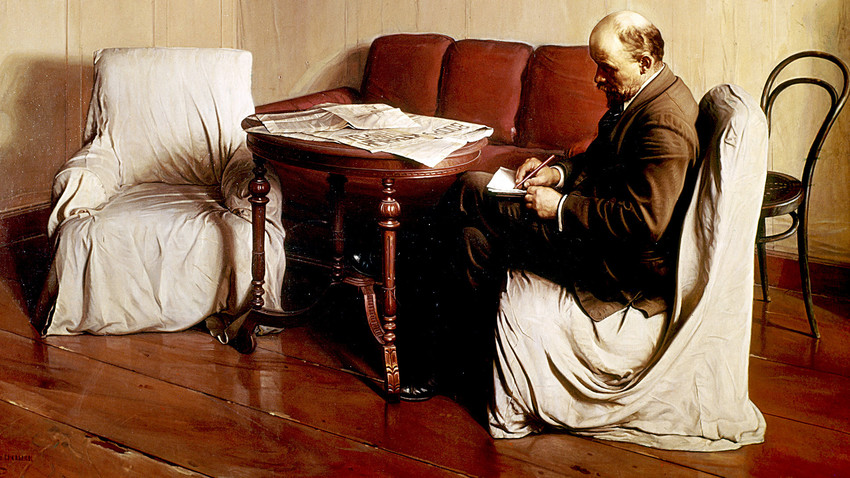

Lenin at Smolny by Isaak Brodsky, 1930

Global Look PressWhen in early February 1918, the Bolsheviks declared that they did not recognize the Romanovs’ debts, it “shocked international finance and sparked off unanimous condemnation by the governments of the great powers.” Overall debts of 60 billion rubles⃰ were repudiated, 16 billion⃰ (the link is in Russian) of which were foreign loans.

Lenin’s decision symbolized a rupture with Imperial Russia, and at a practical level reducing the cost of servicing

The support and intervention stopped, but not because the great powers bent to Lenin’s demands. The Bolsheviks simply got the upper hand in the civil war and the issue of debts owed the main creditors – France and Britain – loomed over the country for decades

France

Between 1880 and 1917, French citizens bought a total of 30 million rubles in Russian bonds and their owners today believe that by now they would be worth around 30 billion euros. It is a belief that is not shared by officials in either Paris or Moscow, and France has never officially raised the issue of Russian imperial debt.

Angry holders of Russian bonds hold their title at the Paris courtroom 26 June 2001

AFPMaybe, as media noted it was due to the fact that in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution Paris confiscated assets that belonged to the imperial government. It also got Russian gold from Berlin amounting to 120 million gold rubles⃰. Berlin received the gold from Lenin’s government in 1918 as part of the Brest-Litovsk peace accord with Germany. It never made it back to Russia. The French took the gold, but never compensated the holders of Russian bonds.

The Russian government stepped in to repay these debts, even though it was not legally obliged to do so. It was a gesture of goodwill in order to secure Russia’s entrance to the Paris Club, the international body for creditor countries to negotiate with debtors when repayment difficulties arise.

In the

Since then, Moscow has repeatedly asserted that the issue is now closed and there are no grounds to discuss any new payments. Still, around 400,000 people in France are seeking billions of euros from Russia with no chance of ever getting the money.

Great Britain

During WWI alone the UK loaned Russia a total of 5.5 billion gold rubles⃰. Overall debts were even bigger. As a repayment

Gorbachev and Thatcher refused reciprocal claims on Tsarist-era debts

APYet, despite this discrepancy, in 1986 Moscow managed to reach an agreement to write-off the debts. Gorbachev and Thatcher refused reciprocal claims. Those Russian funds that had been in British banks since the Revolution were ring-fenced for 10 pence on the pound of the nominal value of Imperial Russian bonds.

Sweden

Stockholm was also one of Russia’s creditors. Shortly before the Revolution Sweden agreed to give a loan

In the early 1930s, Sweden returned roughly

⃰1 gold imperial ruble approximately equals 20 USD.

Read here how Russia freed itself from massive Soviet debts.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox