Party like the last emperor: how Nicholas II squandered the nation’s wealth on celebrations

V. Polyakov, Emperor Nicholas II on the occasion of the opening of the First State Duma of the Russian Empire, 27 April, 1906, St. Petersburg

Getty Images1. Celebrate like a Tsar

Tsar Nicholas II leaves Uspensky Cathedral following his coronation

T. LizovskyNicholas II and his family made their events unforgettable. The coronation of the Tsar and his spouse was the most expensive of all Russian coronations, and the numbers speak for themselves. The military personnel in attendance numbered over 85,000, and they had separate headquarters.

In the Kremlin, a special telephone junction was built to coordinate the ceremonies. Over 24 tons of silver and gold tableware were brought from St. Petersburg. One evening before the coronation, Empress Alexandra was serenaded by a choir of 1,200. This was also the only coronation of a Russian emperor that was filmed.

Nicholas II of Russia and Alexandra Fyodorovna (Alix of Hesse) in Russian dresses. 1913, celebration of 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty.

CGACPPDIn 1913, an even more lavish event took place – the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty, which was organized as a major state and ideological event. Not surprisingly, tremendous sums were also spent. At the Tsar’s order, all civil debts (taxes, fees) were pardoned, and over 1.5 million gold, silver and bronze commemorative medals were made. For the first time in Russian history, portraits of the Tsar and his family were mass-produced on postal stamps, souvenir mugs, handkerchiefs, and more. Perhaps this was done just in case anyone had doubts whose party it was.

2. Dine like a Tsar

Interior of the palace of the Romanov dynasty, built in 1894 on the order of Tsar Alexander III of Russia, 1897

Getty ImagesThe Tsar’s kitchen was manned by 55 people, and three “levels” of cuisine were offered – “simple;” “holiday;” and “parade.” But even “simple” meant a “4-course breakfast; a lunch of 5 courses; and a dinner of 4 courses.”

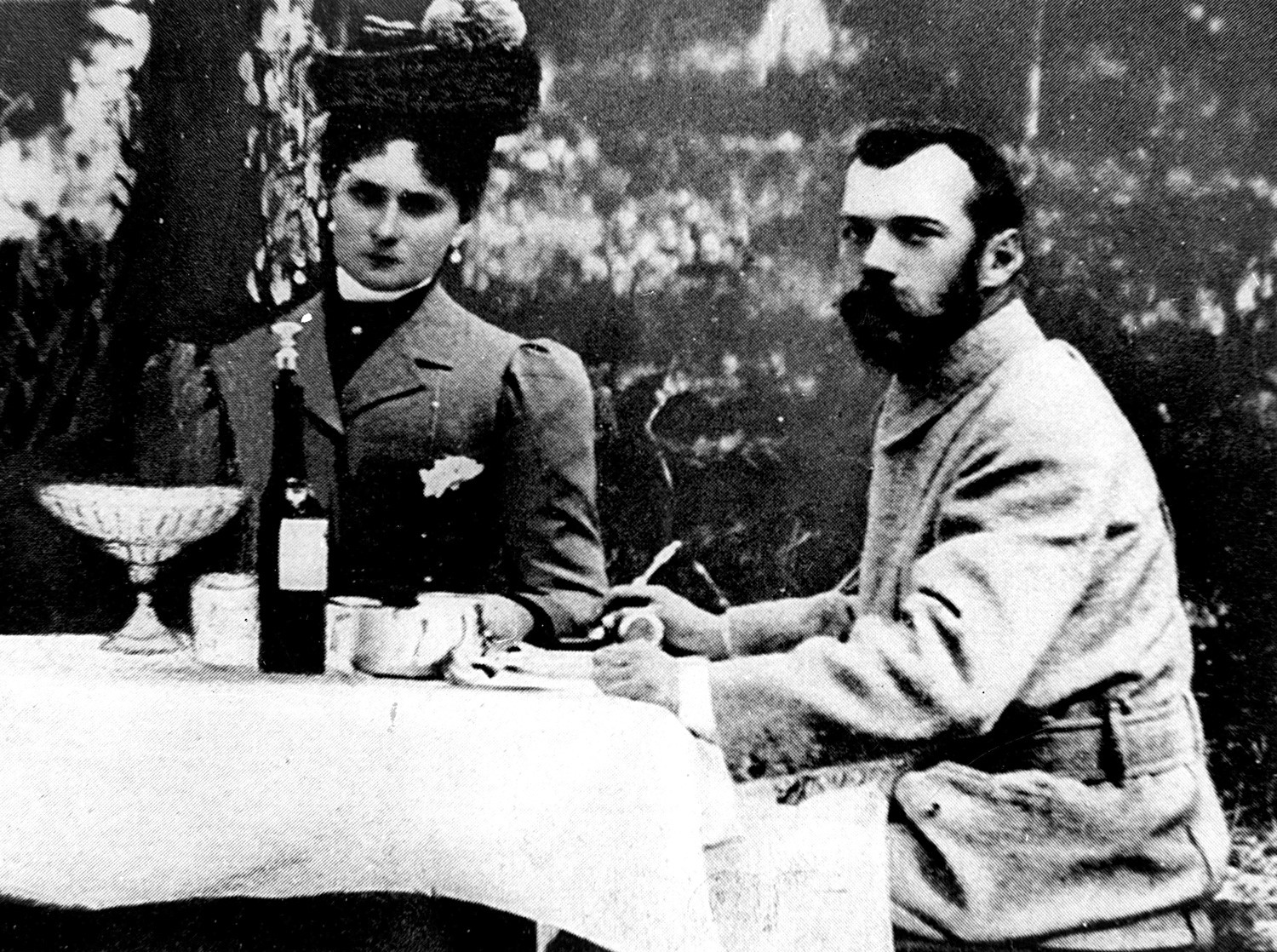

Nicholas II and his wife Alexandra Fedorovna at the table

Getty ImagesSetting the royal table was very expensive, although there was a decline in the cost over the years. In 1901, it cost 71,631 rubles; in 1903 – 67,112 rubles; in 1904 – 47,711 rubles; (an army colonel’s yearly pay was about 4,000 rubles; a horse cost around 100 rubles; and a good piano 200 rubles).

Still, Russia’s royals ate off golden plates, and imported exquisite food from Europe. Even the leftovers from the Tsar’s table were later served as delicacies in St. Petersburg restaurants.

3. Drink like a Tsar

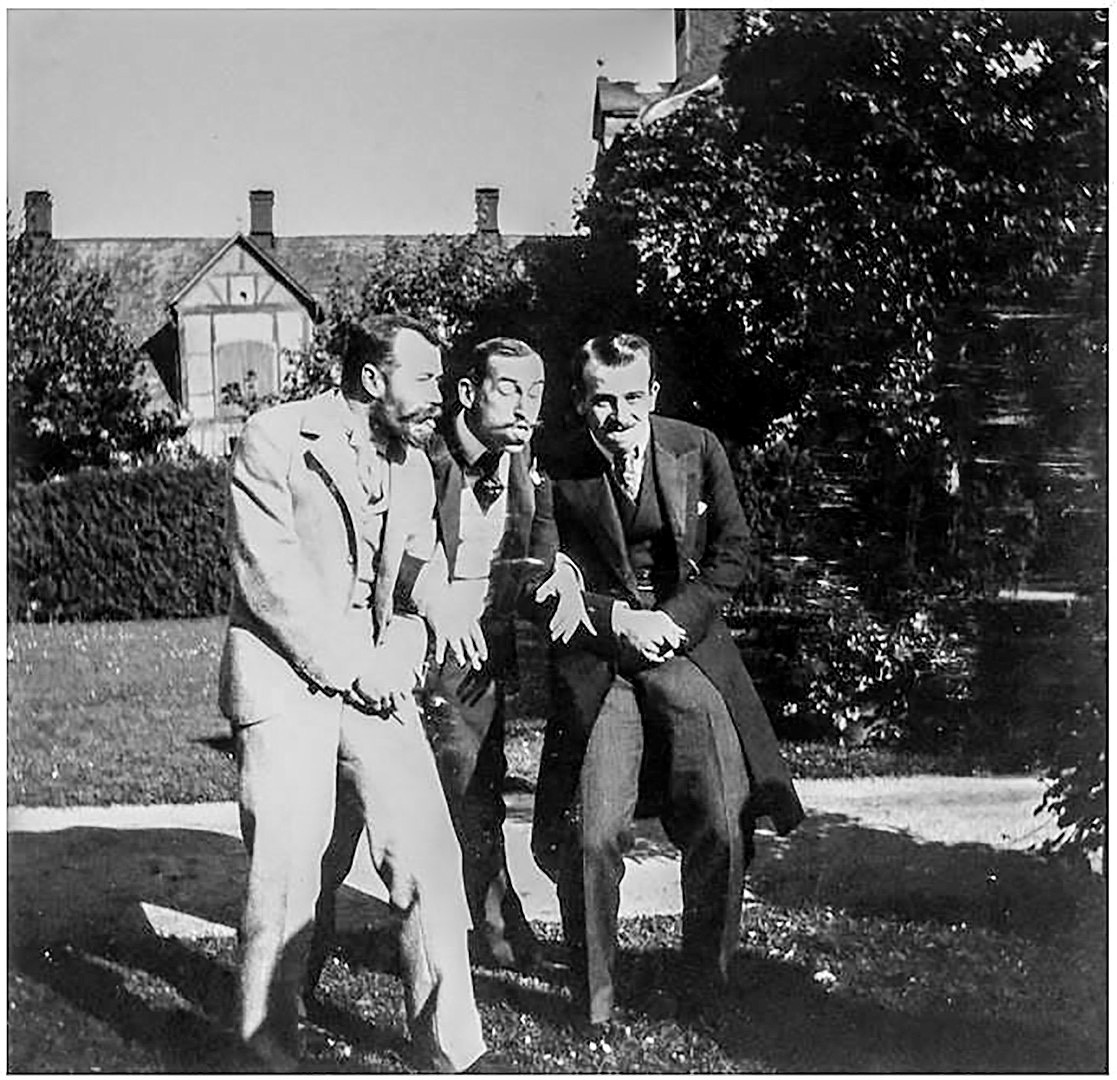

Nicholas II (L) fooling around with his friends, including Prince Nicholas of Greece (R)

State Archive of the Russian FederationNicholas wasn’t a teetotaler, and his favorite drinks were port and plum brandy. In his diary, he left entries like in August 1904, “After visiting the soldiers’ canteens, considerably loaded with vodka, I finally reached the officers’ assembly.” Or during military exercises: “Nicholasha treated us to a great dinner in his tent. I tasted 6 types of port and got a little juiced, which helped me sleep well.”

Even during the harshest of times, in 1916, the Tsar didn’t stop with his drinking habit. As historian Igor Zimin observed, in May and June of that year the Tsar and his family drank 1,107 bottles of wine, 391 bottles of madeira, 174 bottles of sherry, 19 bottles of port (almost exclusively for the Emperor), 14 bottles of champagne (consumed on festive occasions), 3 bottles of cognac and 158 bottles of vodka.

4. Spend like a Tsar

Nicholas II (note his sharp outfit) and Alexandra Fedorovna visit Queen Victoria (Alexandra's grandmother). From left to right: Alexandra Fedorovna; the infant Grand Duchess Olga; Nicholas II of Russia; Queen Victoria of England; Albert Edward, Prince of Wales.

Getty ImagesFrom the day Nicholas was born, he was assigned an annual salary of 100,000 rubles, paid from state funds. After he became emperor, this amount doubled. His 200,000 rubles went straight to his bank account, and for daily spending he was given 20,000 rubles annually. He always exceeded this amount, sometimes spending up to 150,000 rubles a year; (a general or a minister annually earned 6,000-7,000 rubles, and a factory worker up to 500 rubles).

His main expense was charity (building churches, for example) and the posh clothes he needed to visit European courts, especially in the early part of his reign. His wife, Empress Alexandra, spent 40,000 rubles yearly on clothes, and also liked to wear expensive jewelry; for example, in 1914 she bought 25,000 rubles worth of jewelry. Large amounts were also spent on photographing and filming the Tsar and his family. What’s now done with the click of button was once an expensive means of entertainment.

5. Hunt like a Tsar

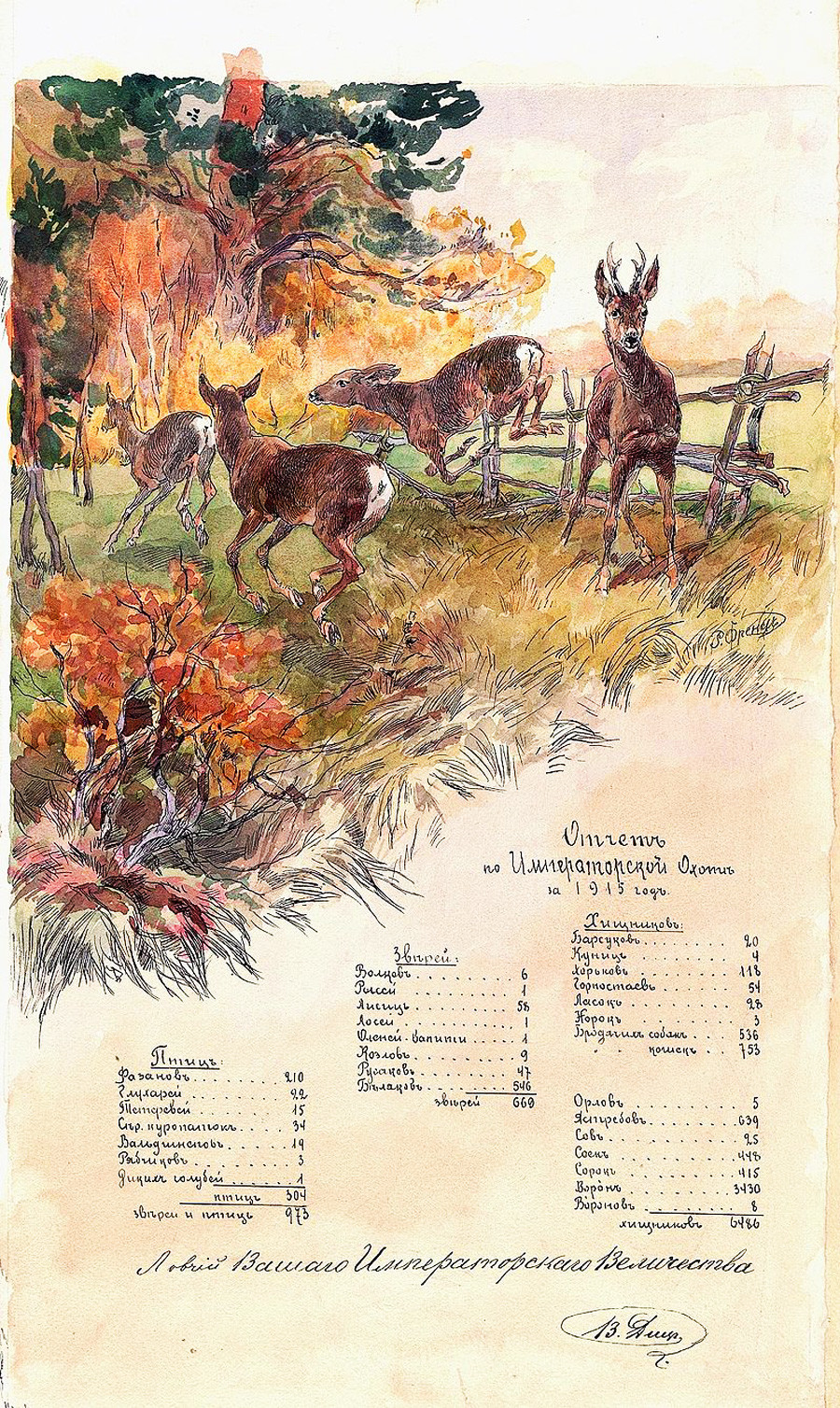

Tsar Nicholas II Romanov of Russia during a hunting expedition in the Bialowieza Forest. Russian Empire, 1897.

Getty ImagesRoyal hunting has long been a favorite pastime of Russian rulers since Ivan the Terrible, and Nicholas II had a passion for hunting as well. A special department in the Ministry of the Imperial Court supervised every hunting season, and there were over 70 men on staff, including a painter, who created amazing watercolors of the hunt (pictured).

A watercolor showing the results of a royal hunt, 1915

Rudolf FrentzStatistics say that in 1884–1909, Nicholas and his brothers and friends killed over 680,000 animals and birds. During one hunt, Nicholas personally killed 1,400 pheasants. The hunts lasted for weeks, and were expensive, with annual budgets of over 30,000 rubles – the equivalent of a year’s pay for 100 elementary school teachers.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox