‘Children’s friend’: The dark story behind Stalin’s popular photo with a Soviet girl

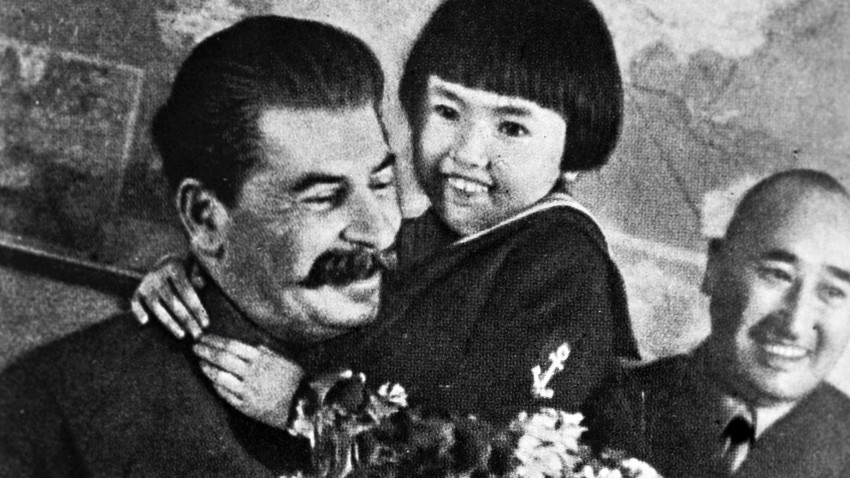

Joseph Stalin is holding in his arms Gelya Markizova (1936). In the two years that followed, her parents were killed in Stalin's purges.

Mikhail Kalashnikov/Sputnik"In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes," Andy Warhol said this in 1968. In 1936, Engelsina Markizova, a seven-year-old Soviet girl from Buryatia, could not have know the phrase – but she did have her 15 minutes of fame after appearing in a photo with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. It did not lead to a favorable outcome, however.

Girl meets leader

Ardan

Ardan Markizov.

Archive photoIt was a great honor for Markizov to have traveled to Moscow with an official Buryat-Mongol delegation to meet Stalin, but it was his daughter who stole the show.

“I also wanted to go see Stalin, and begged my dad to take me with him, but he opposed," Engelsina recalled decades later: "‘You’re not a member of the delegation, who’s going to let you in?’", her father would say. The mother, however, had been supportive.

Surprisingly, it turned out that children were allowed to visit the Kremlin without a special permit, so Markizov took Gelya with him. At some point, after getting extremely bored with the officials’ endless speeches on the progress in their collective agricultural holdings, the child decided to hug the Soviet leader.

“I took two bouquets of flowers and went to the presidium, thinking: ‘I’m going to give him these flowers,’” Markizova said. Although surprised, Stalin looked joyful, held Gulya and put her up on the presidium table, "just like I was – in felt boots.” She handed him the flowers and, when she hugged him, journalists started taking pictures.

Going iconic

Joseph Stalin receiving a bouquet of flowers from Engelsina (Gelya) Markizova.

Getty Images“Do you like watches?” Gelya remembered Stalin asking. The brave girl answered “Yes” (though she had never owned one), and the leader presented her with a gold watch and her family with a gramophone. But those had not been the only presents she would receive.

Anatoly Alay, the director of the unfinished movie 'Stalin and Gelya', quoted the editor-in-chief of the Pravda newspaper Lev Mekhlis as cheerfully saying: “God himself sent us this little Buryat girl. We’ll make her an icon of a happy childhood.” And so it happened: after the photo of Stalin and Gelya (nicknamed 'Children’s friend') was published in all the newspapers, it - as we would say in the 21st century - went viral.

“When I went into the hotel lobby the next day, it was filled with toys and other presents… and when my parents and I went back to Ulan-Ude, people were greeting me like they would greet astronauts later…” Markizova remembered. Georgy Lavrov, a famous sculptor, created a monument to Stalin and Gelya, which became extremely popular. Gelya was everywhere, but not for long.

The fall

A year and a half later, in 1937, everything ended: Ardan

The faraway leader remained silent as Gelya’s life was falling apart. The authorities arrested her mother Dominika as well, and exiled her to Kazakhstan, where she was mysteriously found dead in 1938.

Markizova believed that her mother had been killed as well: the head of the local secret service sent a letter to Lavrenty Beria, Stalin’s chief of secret police, expressing concern that Dominika might try to get herself out using her daughter’s “connection” to Stalin. “On this request, Beria wrote with a blue pencil: ELIMINATE,” she said.

As for Gelya herself, she was wiped out of the official narrative. A tricky issue – Stalin could not be posing for a picture with “the daughter of the people’s enemy”; at the same time, it was impossible to destroy all the newspapers and sculptures. So, with Orwellian cunningness, the officials changed the name of the girl without changing the portrait. From then on, it was Mamlakat Nakhangova, a famous Young Pioneer. Gelya Markizova was erased.

Another life

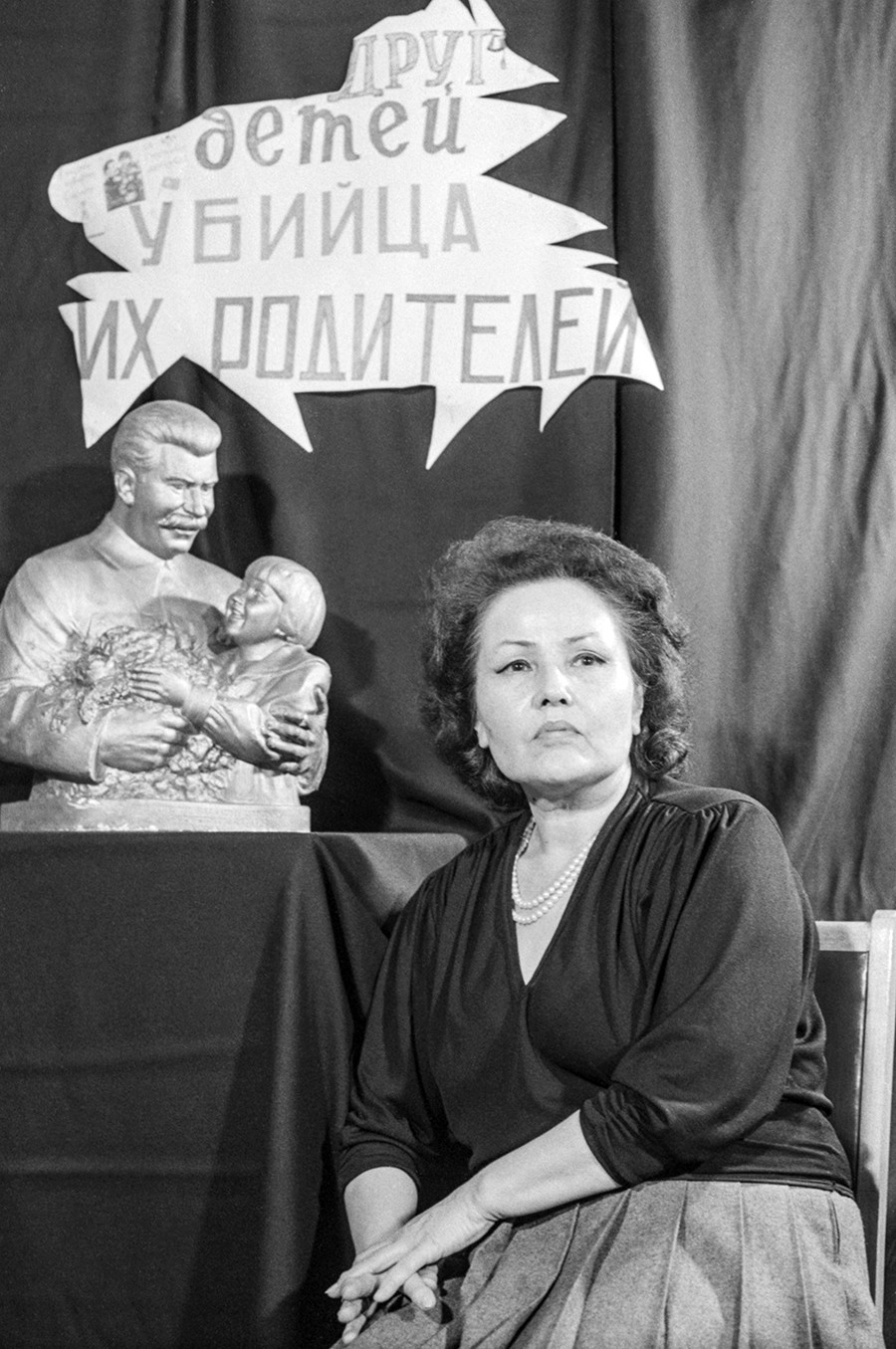

Engelsina Markizova in 1989. The poster behind her says sarcastically: "(Stalin- ) children's friend and killer of their parents!"

TASSThe nine-year-old orphan had made it to Moscow where she had lived with her aunt under her surname – Dorbeyeva. Fortunately enough, the authorities decided against eliminating her as well. “I lived a life of an ordinary Soviet citizen…” she would recall. She was married twice and worked as an Orientalist specializing in Cambodia. In 2004, just weeks after Anatoly Alay started directing a film about her, Engelsina passed away. She was 75.

“Only after people start coming back from the labor camps, and the truth was revealed about Stalin’s era, I understood what he was,” she said, even while recalling how she cried when the authoritarian leader had died, just like many other Soviets would: so charismatic was the “children’s best friend.”

Stalin's purges were harsh: for instance, after WWII he turned his ideological weaponry against Soviet Jews - and it didn't turn out well for them. Read our article on it.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox