49 days at sea: When the U.S. Navy saved Soviet soldiers in distress

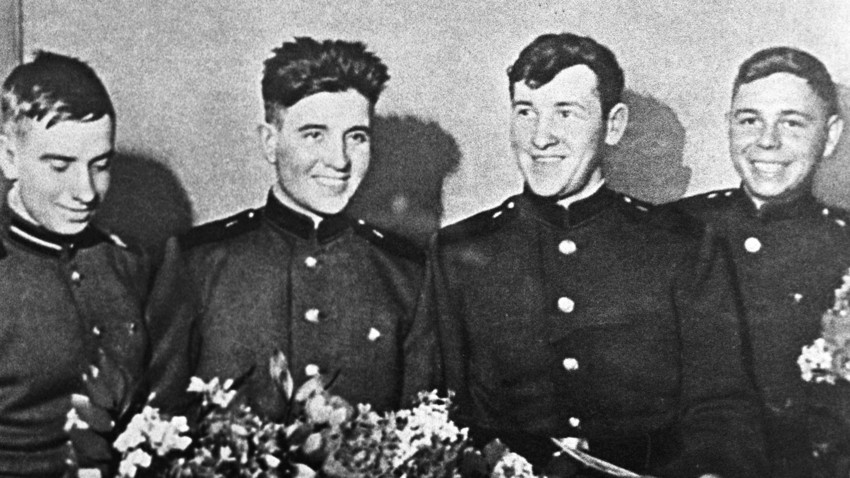

Soviet servicemen from the barge T-36 (left to right) - Askhat Ziganshin, Filipp Poplavsky, Anatoly Kryuchkovsky, Ivan Fedotov

Rudolf Kucherov/Sputnik “About 9 a.m. the storm became stronger, the wire rope broke and the barge headed towards the rocks… The ship was drawn into the open sea. I was told that we had three

Reproduction of the drawing "In a Stormy Ocean" by artists Gorpenko and Denisov from the album of autolithographs devoted to the heroic feat of four Soviet soldiers

SputnikNo food

Four servicemen from Construction Corps - Ziganshin, Fillipp Poplavsky, Anatoly

Reproduction of the drawing "Askhat Ziganshin Cooking Dinner" by artists Gorpenko and Denisov

SputnikNo quarrels

By Feb. 23, however, the food was gone. They tried to catch some fish, but no fish were to be seen. Sharks, however, were circling. So, the four boiled and ate their leather boots and belts, as well as the leather parts of an accordion. In the end, their bodies weakened and hallucinations set in.

The most remarkable thing, however, was the fact that in those terrible conditions they managed to keep

“There was no panic or depression until the very end. Later, a mechanic on the Queen Mary that brought us from the U.S. to Europe told me that he had been in a similar situation: after a strong

Nothing like this took place on barge T-36. They divided their supplies equally and didn’t try to get any advantages at the expense of the others.

Afraid to become deserters

By March 7 they only had half a kettle of fresh water, one leather boot and three matches left … Fortunately, they were found by the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, Kearsarge. At first, the Soviet servicemen did not want to leave the barge,

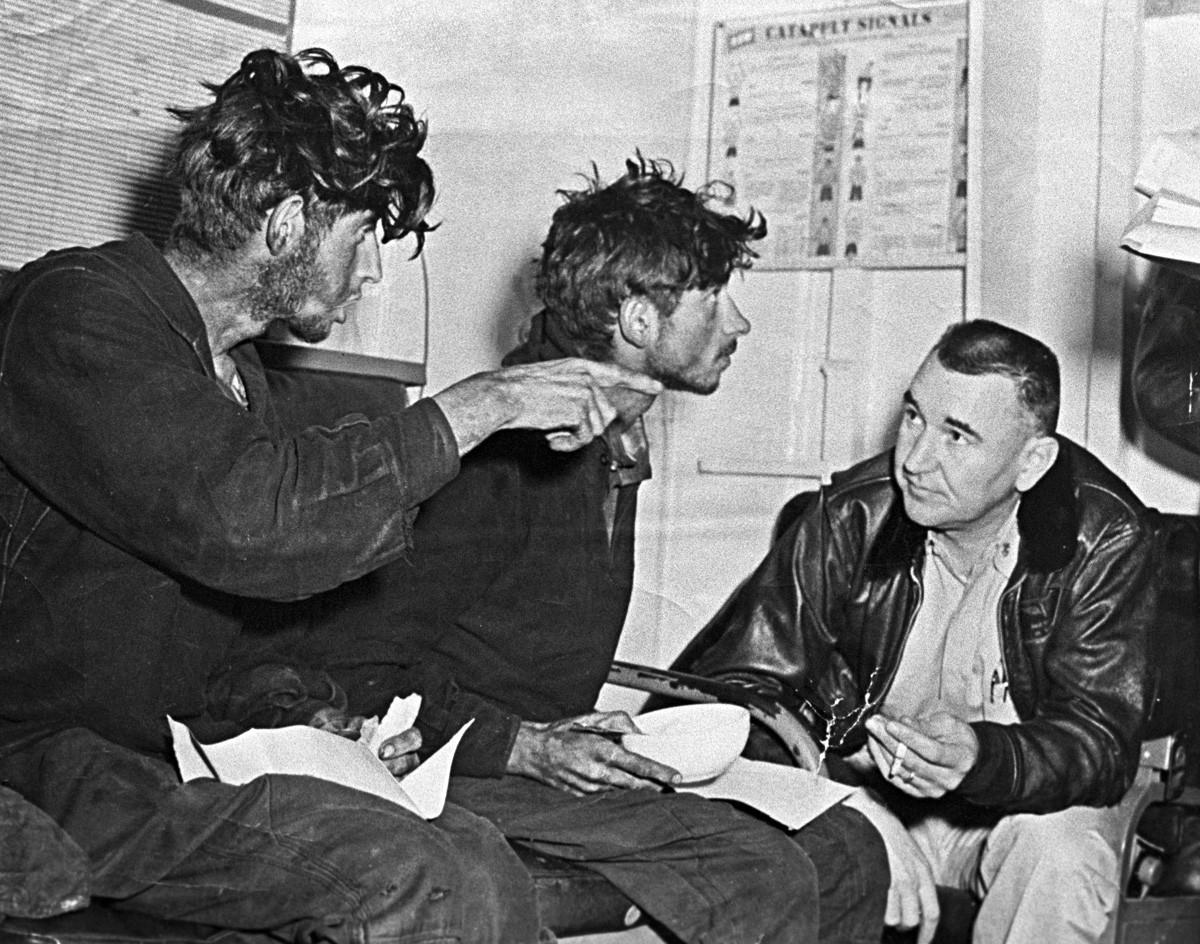

The emaciated Filipp Poplavsky, left, and Askhat Ziganshin, center, retell their plight to an American sailor after rescue on board the U.S. "Kearsarge" aircraft carrier

SputnikThey changed their minds, however, and went

Greeted like heroes

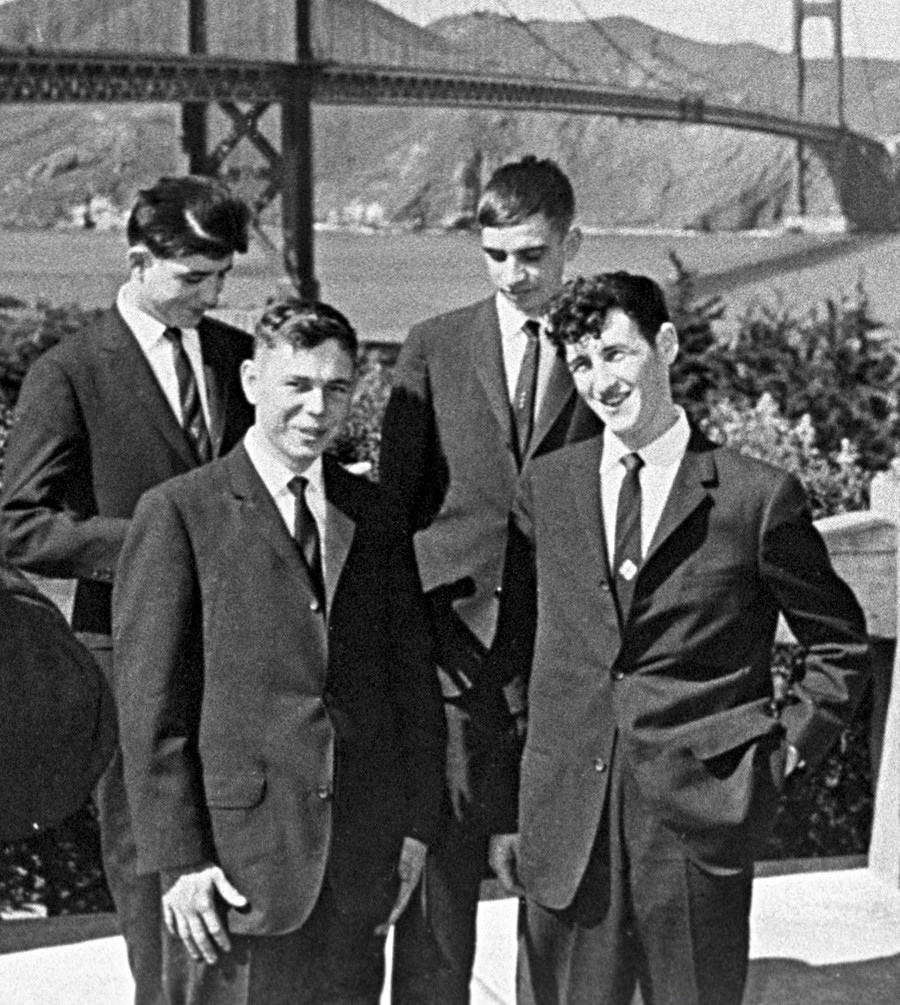

Their worries, however, proved to be in vain. Soon, one of the main Soviet newspapers published an article about them, “Stronger than Death.” They were heroes both in the USSR and in the U.S. They received a heroes’ welcome in San Francisco (the mayor gave them a symbolic key from the city), as well as in New York

The four Soviet servicemen being photographed on an excursion in San Francisco

Rudolf Kucherov/Sputnik

A meeting in Vnukovo airport on the arrival of the four servicemen in Moscow

Udovichenko/Sputnik

Read here how the USSR and U.S. battled each other with radio waves during the Cold War

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox