How did the Russian army fight alcoholism?

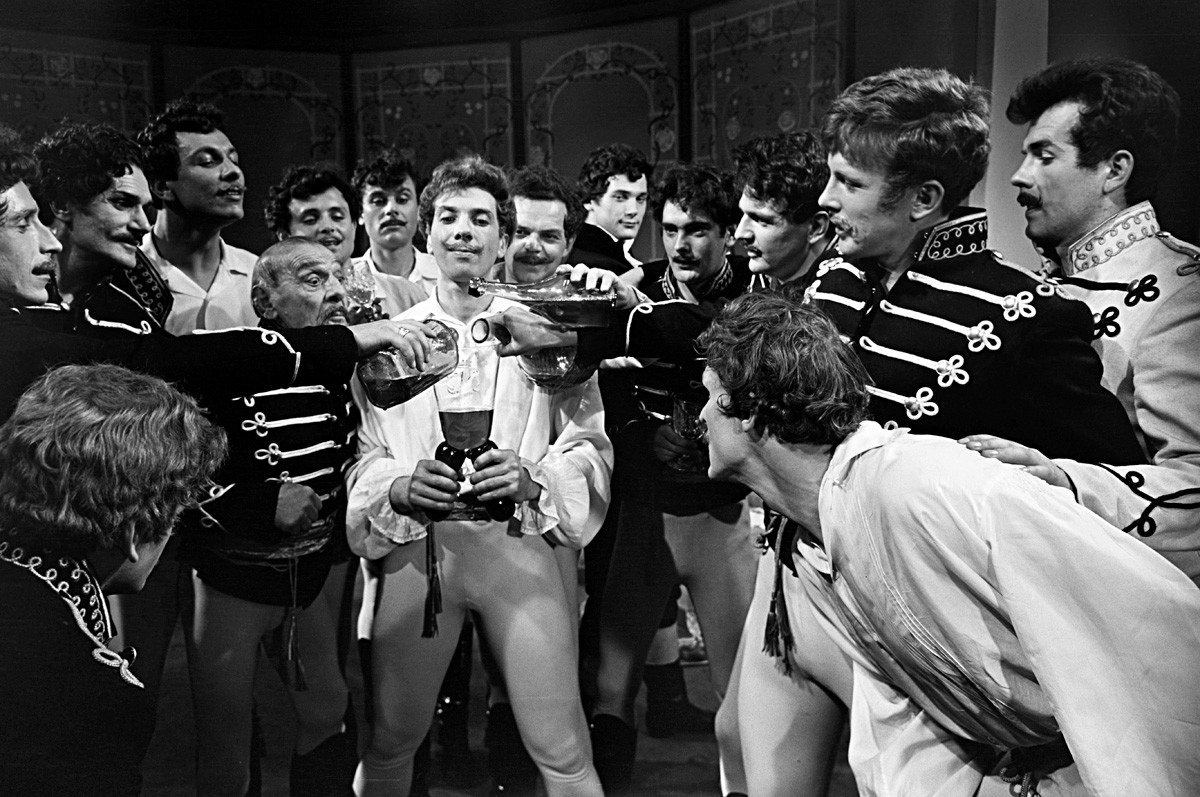

In the recent American-Turkish movie “The Ottoman Lieutenant” (2017) we see how during WWI an Ottoman officer secretly infiltrated a stronghold captured by the Russian army. There he found masses of blind drunk Russian soldiers who even couldn’t stand up straight because of the booze.

Such impression of the Russian army is common for Hollywood, but is very far from reality and simple logic: how could Russian troops fight effectively, capture enemy strongholds and win if they were a horde of undisciplined drunkards

Alcohol versus disease

Alcohol wasn’t forbidden in the Russian army in the 18th century. On the contrary, back then it was considered the most effective means to fight disease and epidemics, as well as hunger and cold.

Each soldier daily got two cups of wine or vodka: one in the morning, another in the evening. And his ration included three liters of beer. For outstanding service, a soldier could earn an additional portion of booze.

However, Russian Emperor Peter the Great never allowed his troops to get trapped in a drunken downward spiral. Drunk soldiers were punished with a whip, and drunk officers could be reduced to the ranks. Besides the stick there was also a carrot: if a soldier refused his portion of booze, he got a raise in salary

In

Struggle against alcoholism

In the early 20th century medicine reached a proper level, and it became absurd to see booze as the main cure. The state began to fight alcohol dependence in the military: soldiers got only three cups of the booze per week, and attempts were made to replace alcohol with traditional Russian drinks such as kvass and

During WWI, alcohol was prohibited in the Russian Empire. This act wasn't warmly welcomed by the Russian soldiers. They searched for enemy wine storages during offensives or tried to use eau de cologne as a replacement, which resulted in mass intoxications

‘100 grams from the People's Commissar’

The uncontrolled alcohol madness faded away with the horrors of the Revolution and Civil War. There was no place for alcoholism in the Red Army.

During the Winter War between the Soviet Union and Finland, the situation changed. The People's Commissar for Defense (Minister of Defense) Kliment Voroshilov ordered daily portions of vodka (100 grams) for the frost-bitten soldiers to raise their combat spirit.

The tradition of “100 grams from the People's Commissar” (as these portions became known) continued during the first critical period of the war against the Nazis

Alcohol was also given to soldiers before attacks, but others had to wait for major state holidays to receive their 100 grams.

Those who overdid the alcohol could face serious punishment. In some cases, drunk servicemen stripped of their rank were sent to penal battalions “to wash out their shame with blood.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox