Stalin’s lifehacks: How to ruthlessly take power and get away with it

If Joseph Stalin somehow ended up in the Game of Thrones world, we know, who would have taken the Iron Throne.

Getty Images; Global Look PressStalin’s archenemy, Leon Trotsky, used to call him “the most outstanding mediocrity of the [Soviet communist] party”. The joke was on Trotsky: “the mediocrity” defeated him in the political struggle, squeezed him out of the party - and the country - and finished him in 1940, sending an assassin.

Trotsky and other senior communist hierarchs, such as Grigory Zinoviev or Nikolai Bukharin, might have had no idea how a modest man who used to take an utterly bureaucratic position in the party’s apparatus outplayed them in the Soviet power struggle. But today, almost a hundred years later, we can analyze Stalin’s success and identify what had helped him become basically the Darth Vader of Russian history.

(Disclaimer: Russia Beyond does not approve of Stalin or his methods.)

Lifehack 1: Take any job you can

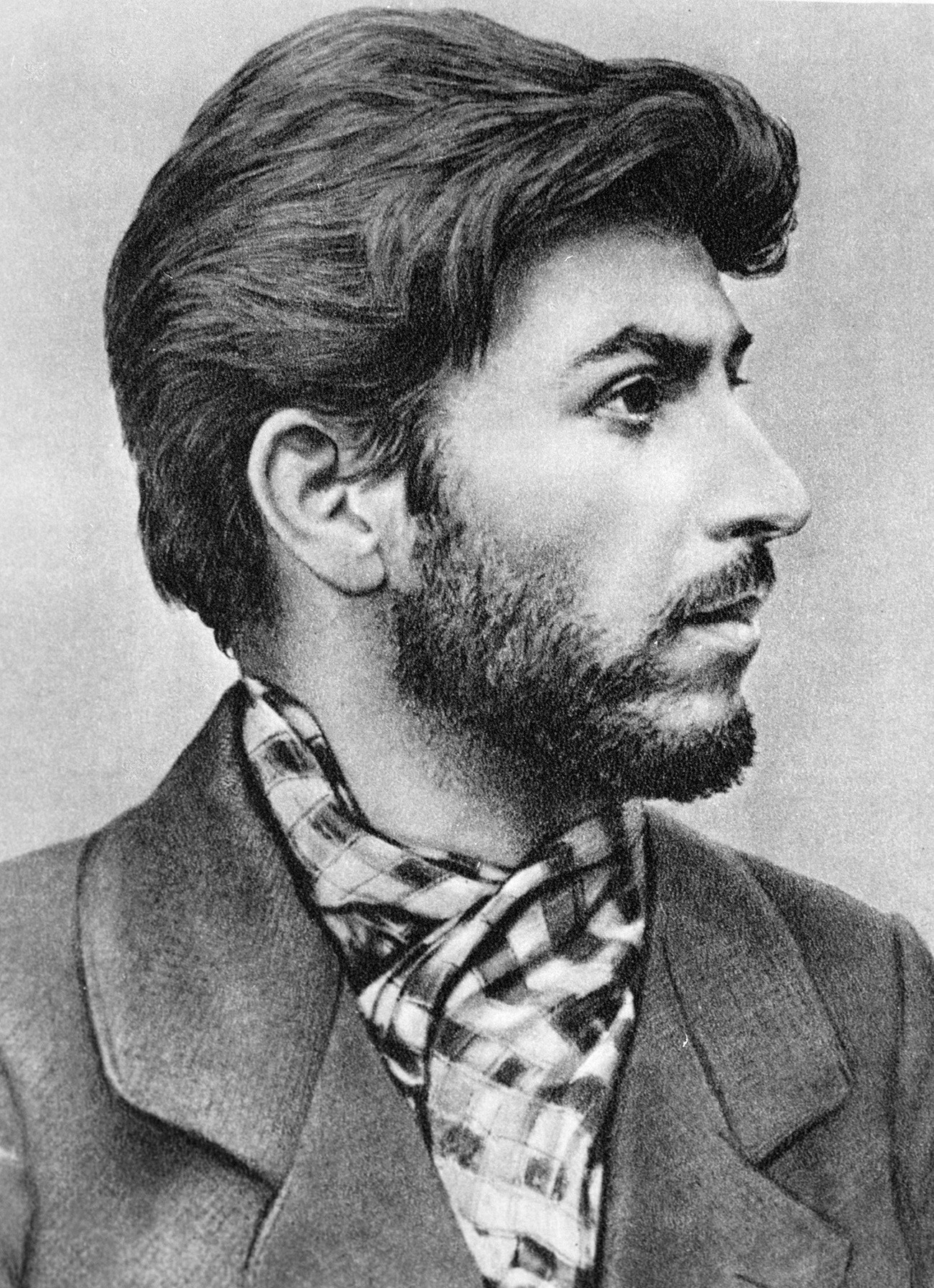

Stalin in his younger years.

SputnikThis probably won’t surprise you, but Joseph Stalin wasn’t squeamish, even if we’re not talking about signing execution orders. He joined the Bolshevik circles in 1901, in his early 20s, and was doing everything the party asked of him: established printing presses to publish Bolshevik newspapers, wrote articles, contacted deputies in the State Duma, even did illegal work.

The proactive approach worked: in 1912, Stalin was appointed to the Central Committee of the Bolshevik party, the socialist elite and future leaders of the USSR. Back then, though, it meant living a thug’s life: after being captured by the Tsar’s police, Stalin spent four years in Siberian exile. No wonder he was angry when he came back to Petrograd (by then St. Petersburg) after the Revolution prevailed in 1917.

Lifehack 2: Be loyal to your boss (insofar as he’s tougher than you)

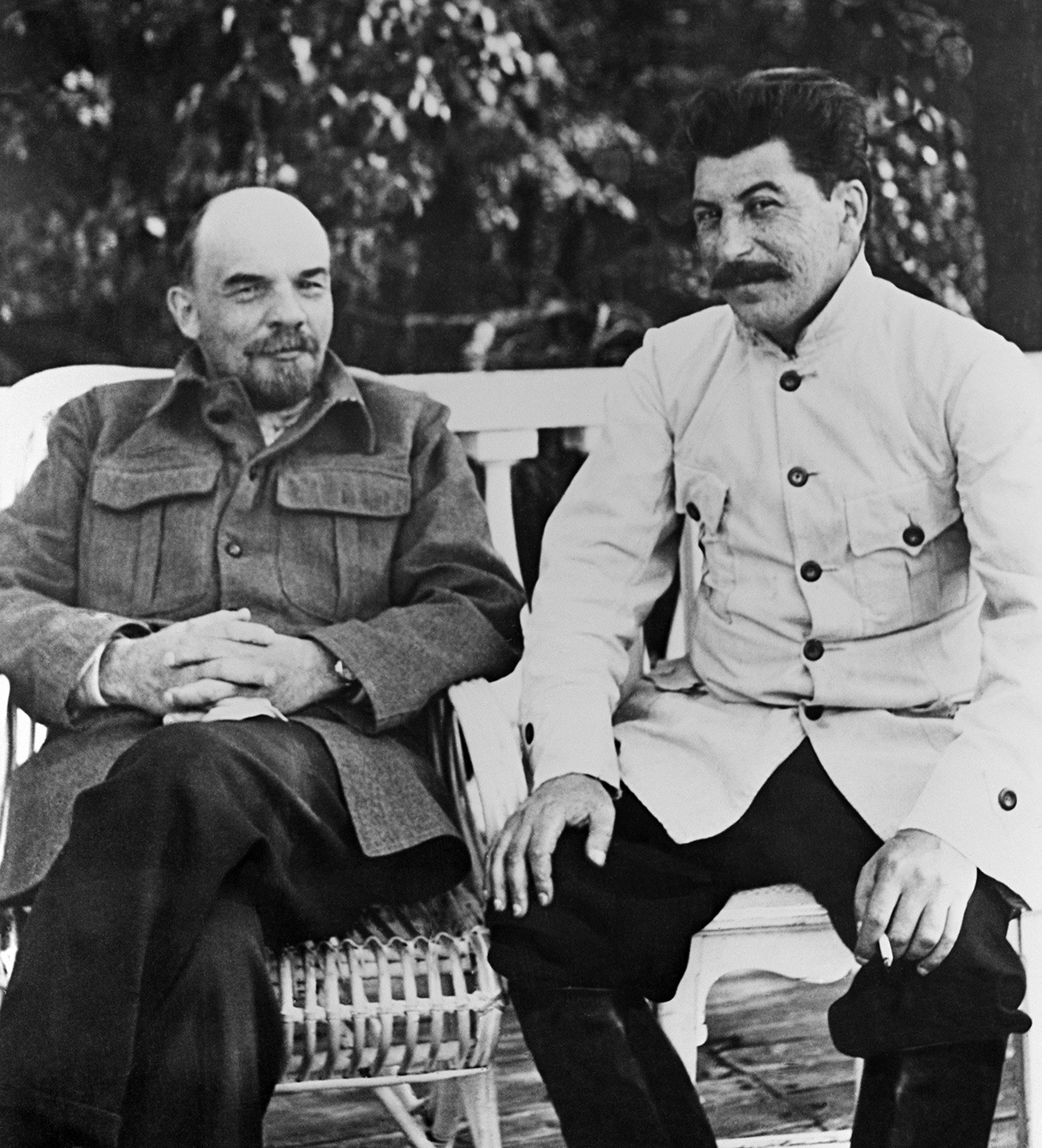

Joseph Stalin and Vladimir Lenin in the countryside.

SputnikIn the early 1910s, Vladimir Lenin shone brightly as a leader of the Bolshevik party, the most influential ideologist and enemy of capitalism. Stalin never questioned his authority, though he might have been intimidated with Lenin’s lack of attention towards him during Stalin’s early years.

Once Lenin even forgot Stalin’s real name while he was in exile. “There were Lenin’s requests sent to different Bolsheviks in 1915: “Do you remember Koba’s [Stalin’s pseudonym] surname? Please, remind us Koba’s surname… Joseph something? We forgot,” wrote Oleg Khlevniuk in Stalin’s biography.

After the revolution of 1917, though, Lenin remembered Stalin very well: he was among the first Bolsheviks to arrive to Petrograd and start organizing workers to rebel, even before Lenin himself had come back from Switzerland.

At first, Stalin took a moderate position, coalitioning with other socialist parties, but quickly changed his mind after Lenin expressed his far-left views, proclaiming the seizure of power and world revolution. “Stalin, as always, followed Lenin’s lead in policy; he was a devoted and loyal ally of Lenin’s. Of course, Lenin appreciated that” Oleg Khlevniuk writes. Until 1922, when Lenin, being extremely ill, bashed Stalin for his “crudeness”, the two had enjoyed an amicable relationship, which helped Stalin a lot. As for the later conflict, Lenin had no time to deal with Stalin, eventually dying in 1924.

Lifehack 3: Talk less and never underestimate bureaucracy

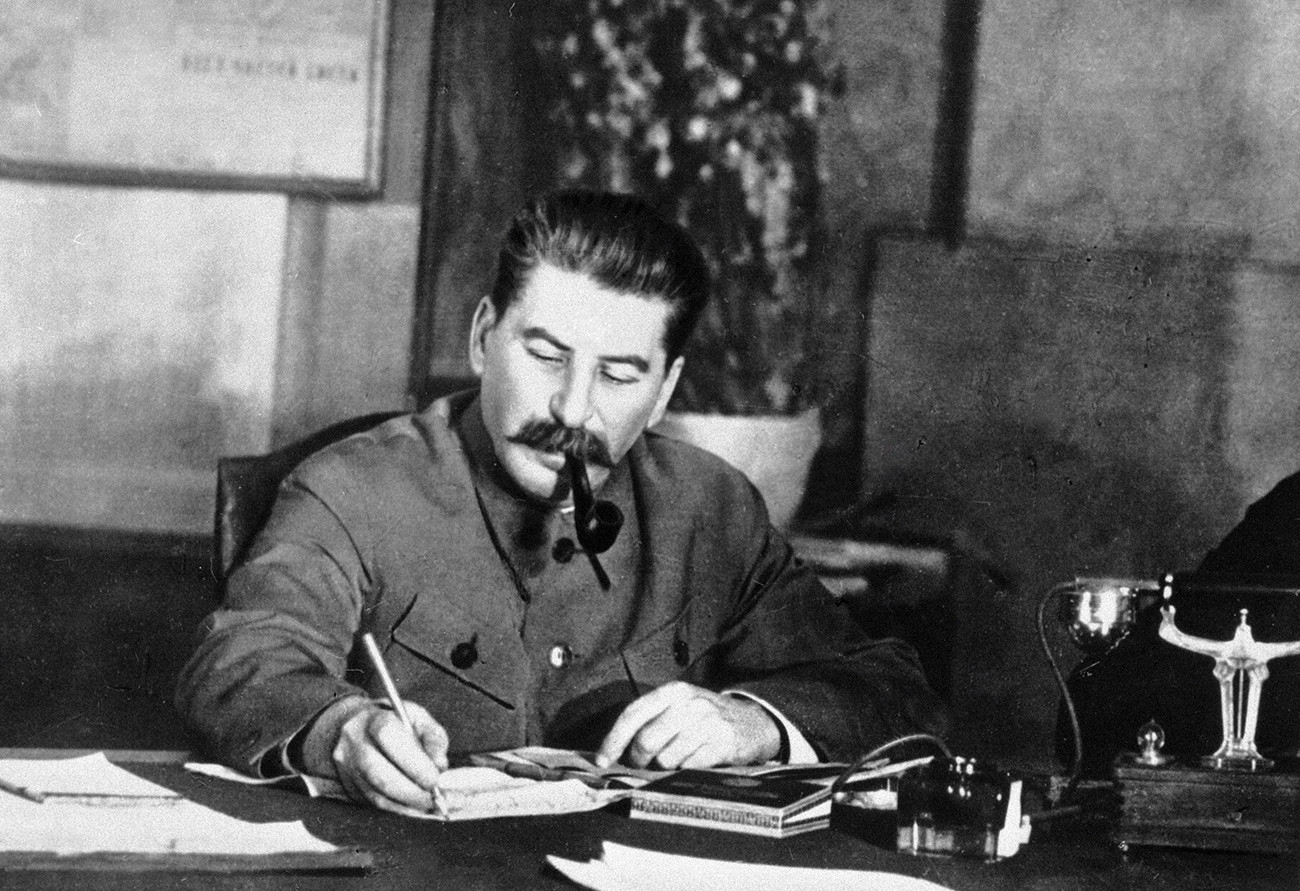

Stalin at work, maybe masterminding some dreadful plans.

SputnikUnlike Leon Trotsky or Grigory Zinoviev, famous for their eloquence, Stalin never was a good orator – but he was good at working hard in mundane positions. After the Bolsheviks won the Civil War of 1917-1921, and proclaimed a new, red Russia, Stalin had led a minor People’s Commissariat of Nationalities – he himself mentioned that “the committee is all about campaigning, not administrative rights.”

However, since 1922, Stalin became the General Secretary of the All-Union Communist Party, heading its rapidly growing bureaucratic apparatus. That position was also considered to be mostly technical, but Stalin had had an impact on mid-level party functionaries and managed to “recruit” many Bolsheviks to his camp.

At the same time, for a while he remained modest and low-key… and underestimated by his rivals. “Concentrating himself on routine jobs, Stalin appeared to most Bolsheviks as a thoughtful, balanced leader; moreover, a real workaholic, doing real work, not a loud rhetorician,” explains historian Alexei Volynets. That’s why during the 1920s clashes among the Bolsheviks’ elite, Stalin usually had the majority of low- and mid-level Bolsheviks on his side.

Lifehack 4: Make alliances, break alliances

Communists at the Congress of Soviets of 1927. Stalin is in the center. The man to his right is Nikolai Bukharin, his ally whom he would send to the executioners later.

TASSWhat’s the best way to defeat multiple rivals and become a real king of the hill? To pit every one of your enemies against each other, carefully changing sides. That’s what Stalin did in the 1920s.

First, in 1923, along with Grigory Zinoviev and Zinoviev’s ally Lev Kamenev, Stalin attacked Trotsky in a predictable move. “Before the revolution Trotsky opposed the Bolsheviks, joining Lenin’s ranks only in summer 1917,” Volynets writes. So “the big 3” – Stalin, Zinoviev and Kamenev – using their collective influence, expelled Trotsky out of the Red Army that he had earlier helped to create and led for several years.

Second, Stalin turned his guns against Zinoviev and Kamenev, who had had to side with Trotsky in 1925, creating “the united opposition”. But it was too late. Along with more moderate leaders, such as Nikolai Bukharin, Stalin labeled Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev left-wing radicals, and in 1926-1927 strong-armed them into leaving the party’s Central Committee.

Then, it was Bukharin’s turn: in 1928 Stalin, supported by the party’s majority, smashed him as a right-wing opportunist, also depriving him of any leadership posts. The field was almost clear: by the 1930s, all of the old-guard Bolshevik leaders from the first echelon were either exiled (Trotsky) or disgraced (Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin).

“The Russian revolution started to eat its own children, as it had already happened to the French revolution,” summarized Oleg Khlevniuk. But for Stalin – unlike for the hundreds of thousands of Soviet people killed during the Great Purges of the 1930s – the future was brighter than ever. His absolute power could have easily been the envy of 19th-century emperors.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox