How Russians flooded the U.S.

Russian immigrants were a feature of the U.S. since its earliest days. According to the first American Census of 1790, their number exceeded 10,000.

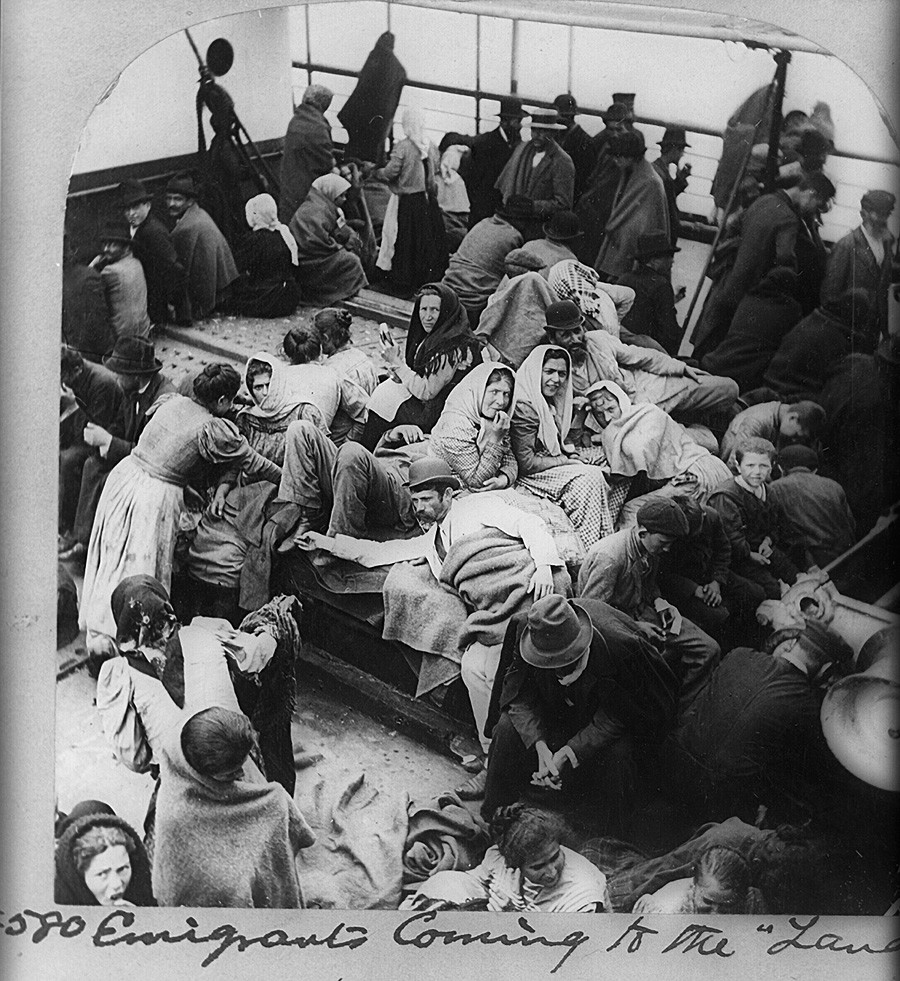

Every social or political shock in the Russian Empire caused mass emigration abroad. People went to the U.S. in search for freedom or a better life: Poles after the suppressed Polish uprisings, Jews, Armenians, and, of course, Russians: peasants, intelligentsia and numerous persecuted religious sects followers.

Although only some 7,550 Russians came to the country during the half century from 1820 to 1870, their numbers sharply increased in the years to follow. The 1920 U.S. Census identified 392,049 United States citizens born in Russia.

When in the second half of the 19th century, Russia descended into a period of political struggle and terrorism, the number of political émigrés to the U.S. significantly increased. Full of revolutionary ideas, Russian political immigrants, along with their like-minded brothers from Germany and Italy, played a huge role in spreading radical, anarchistic and left-winged ideas in the U.S. One of the main American anarchist ideologists of those times, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, originated from Lithuania, part of the Russian Empire.

Defeat in the 1905 Russian Revolution gave an added impetus to the flow of revolutionary types to the U.S. In 1908 in New York one of the largest and most influential political associations of Russian immigrants - the Union of Russian Workers, which actively promoted anarchist ideas, was established.

By the late 1910s, the radical movement in the USA, in which Russians played a significant role, was so strong that the country was gripped by the so-called Red Scare - fears that an insurrection similar to the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution could be witnessed in America too.

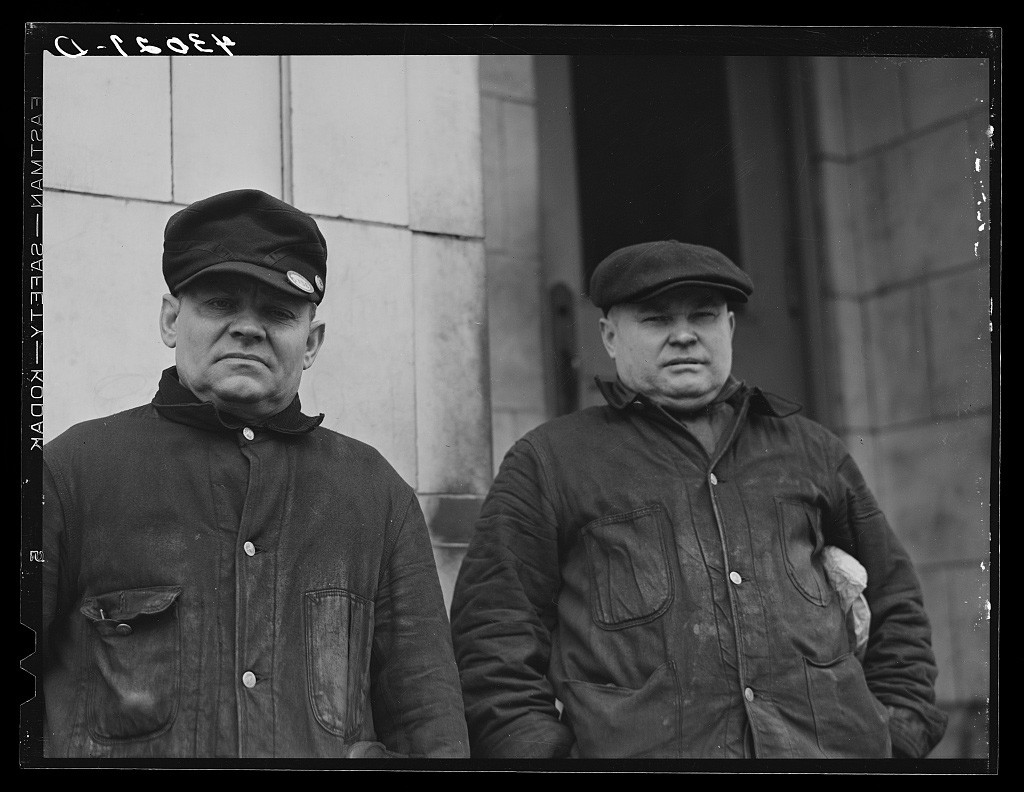

As a result, the government initiated mass arrests of “anarcho-communists” across the country. These so-called Palmer Raids of 1919 and 1920, were led by the Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and his associate, future first FBI director Edgar Hoover. As one Russian immigrants to the U.S., writer Ivan Okuntsov noted in his “Russian Immigrants into North and South America:” “Russians’ life after the Palmer Raids became unbearably hard. They generated suspicions to each Russian, no matter what political views he supported. Without a reason Russians were fired from factories and plants.”

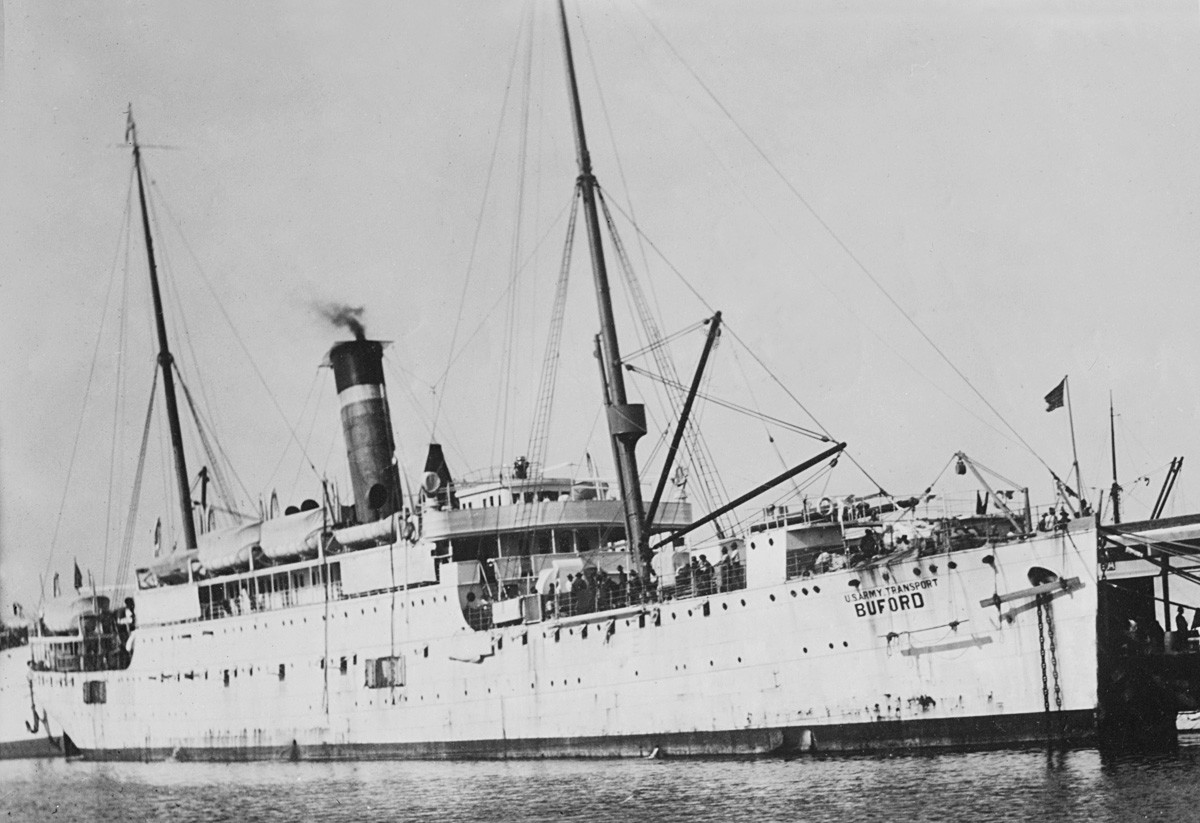

Thousands were deported. On December 21, 1919, the passenger ship, the USAT Buford with 249 seized radicals onboard, left New York harbor and headed to Soviet Russia, as a “Christmas present to Lenin and Trotsky.” Goldman and Berkman were among the passengers of this Soviet Ark, as the press called it.

USAT Buford

Library of CongressHowever, Russian immigration to the U.S. in the first half of the 20th century wasn’t only made up of revolutionaries. Numerous artists, poets, authors and scientists were forced to leave Russia after the 1917 Revolution and settled in North America. These so-called White émigrés drastically changed Americans’ low opinion about Russians.

The 1920s was a highlight for Russian culture in the U.S. Prominent Russian cultural figures, who chose America as their new homeland (such as famous composer Sergey Rachmaninov and painter Nicholas Roerich), organized successful ballet, opera and theatrical performances, art exhibitions.

Sergei Rachmaninov

Getty ImagesBeside culture, Russians made a significant contribution to American scientific life. Such leading scientists as aviation pioneer Igor Sikorsky and developer of television technology Vladimir Zworykin, lived and worked in the country. They also helped American society to forget about the Russophobia of the earlier years, at least until the start of the Cold War.

Vladimir Zworykin

Getty ImagesIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox