Where did Russia’s symbols of monarchy come from?

Holding the

Staffs and scepters of the Rurikids and the Romanovs

Ivan the Terrible Showing Treasures to the English Ambassador Jerome Horsey, by Alexander Litovchenko, 1875

The Russian Museum

Coins of Prince Svyatopolk and Vladimir the Great

Grigoriy Tyukanov (CC BY-SA 3.0), Hermitage MuseumSuch a staff can be seen on ancient Russian coins of Vladimir the Great and Prince Svyatopolk. On them, the prince is holding a staff adorned with a cross – such pictures are also found on Byzantine coins of the same era.

A rod, or a scepter, is slightly different – it’s shorter. A rod was used in the military of the Roman Empire as a commander’s attribute, and later, in the Middle Ages, rods were adopted by European monarchs as their attribute of military and secular power.

Ivan the Terrible by Viktor Vasnetsov

Tretyakov GalleryThe first rod in Russia was probably depicted in the illustrations to the Radziwiłł Chronicle (13th century), where Sviatoslav II of Kyiv holds a

In 1553, English envoys Robert Chancellor and Clement Adams recorded that Ivan the Terrible met them seated on a “gilded seat, with a crown on his head and with a scepter made of crystal and gold in his right hand”. Since then, the tsar always held a scepter during ceremonies.

But, Ivan the Terrible always carried a staff with him as a symbol of his power. Jerome Horsey, another English diplomat in Russia, recorded that Ivan believed his staff, made out of “unicorn’s horn”, had healing abilities! During a conversation with Horsey, Ivan announced: “I am poisoned with

Feodor (Fyodor) I Ivanovich (1584 - 1598)

Viktor Kornushin/Global Look PressDuring the coronation of Feodor I of Russia in 1584, Feodor used both the staff, that he held, and the scepter and orb, that both were carried on a pillow before him. Unfortunately, Feodor’s scepter didn’t survive to our days.

Orb and scepter, part of the Grand Attire of Czar Mikhail Romanov. Moscow Kremlin Armory Chamber.

Balabanov/SputnikThe oldest known scepter of the Russian tsars was the one used by the first Romanov, Mikhail I of Russia, at his coronation and beyond. This scepter was most likely received as a gift from Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. Another one, used by Alexis of Russia, came from Istanbul in 1662, together with an orb.

The Russian Imperial scepter. The RF Diamond Fund.

Yuriy Somov/SputnikDuring Peter the Great’s coronation, Peter used an old-styled scepter made in Moscow – this one looked much like the scepters of the Rurikids. But in 1762, Leopold Pfisterer, an Austrian jeweler under Russian service, made an Imperial Scepter for Catherine II, which has been used in coronations ever since.

In 1774, the Orlov Diamond was mounted onto the scepter. It’s 59.6 cm in length and weighs 604 grams. 395 grams of gold, 60 grams of silver and 193 diamonds were also used to make the scepter. Since 1967, it’s on display in the Diamond Fund in the Kremlin Armoury.

The cross upon the world

The orb of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich (1629-1676). Istanbul, 1662.

Sergey Subbotin/Sputnik

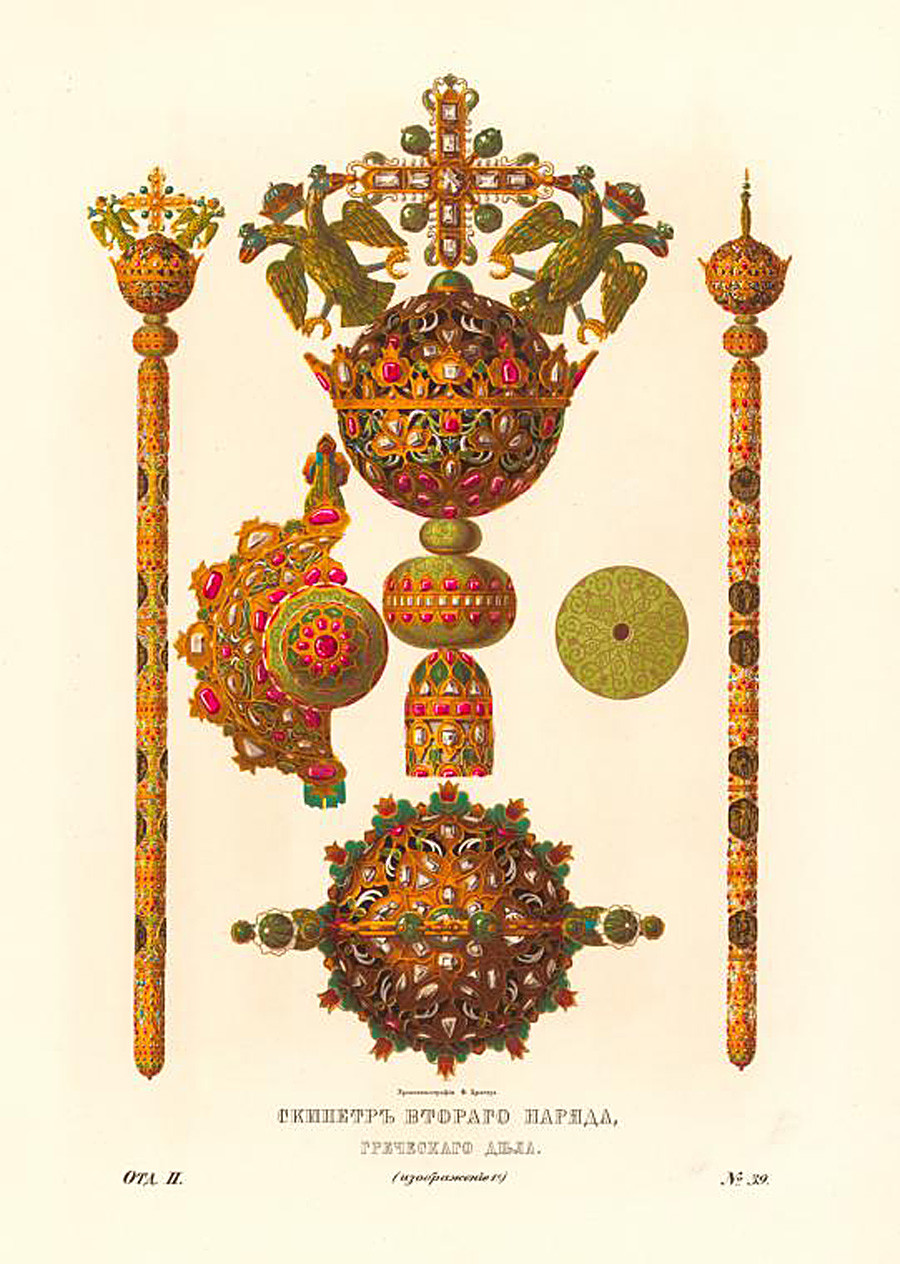

Orb and scepter from Istanbul (1662)

Fyodor Solntsev/Antiquities of Russian country, 1846—1853With the development of Christianity, the orb was topped with a cross. The Emperor held the orb (the world) in his hand, to show he ruled it on God's behalf. Just like the scepter, the use of the orb was adopted from Constantinople by the Russian tsars

The orb of Peter II

Shakko/Wikipedia

The Russian Imperial orb.

Yuriy Somov/Sputnik

Finally, the Imperial Orb, which is 24 cm high and 48 cm in diameter, was made for Catherine II by the court jeweler Georg Friedrich Eckart. It is a smoothly polished golden globe, surrounded by diamond belts

The Imperial Orb and the Imperial scepter (copies)

Boris Kavashkin/TASSIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox