Who were ‘thieves-in-law’, Russia’s violent mafia bosses?

On a winter day in January 2013, the head of the Moscow police arrived at a crime scene. A man had been killed in broad daylight in the center of Moscow. A bullet had entered the victim’s head, resulting in his death. And there was no need to reach for deceased’s wallet for an ID: the stout face of Ded Khasan [Old Man Khasan], one of the most influential “thieves-in-law” in the country, was well known.

The Russian streets in the 1990s were packed with criminals. But how did bandits become the feared and influential vory – thieves – and why were they dubbed as “in-law?”

Thieves of Stalin’s Gulag

Vory existed in Tsarist Russia, but it was Stalin’s repressions that shaped them into a distinctive class. In the Gulag camps, bitter inmates rejected the legitimate world and created their own violent subculture that had a strict hierarchy, its own language, and an unwritten “honor code”.

Thieves disdained the law, but swore to live by the code, the new “law” of their own making. Breaking it would often result in a death sentence.

The often fatal journey into the Russian criminal underworld always began with petty crimes.

Infamous criminal boss Aslan Usoyan, known as Ded Khasan, served his first sentence at only 19 years of age. He was found guilty of resisting the police officers and, later, served a few sentences for illegally dealing in foreign currency and robbery.

Infamous criminal boss Aslan Usoyan served his first sentence at only 19 years of age.

Archive photoWith time, Ded Khasan would arguably grow to become the most influential criminal boss – “thief-in-law” – not only in Russia, but also across the CIS.

Although much of the influence Ded Khasan and other mafia bosses exerted over the Russian criminal underworld of the 1990s was thanks to their violent nature, ruthlessness, and willingness to take bold risks, there also was a mysterious ceremony that officially bestowed the title of thief upon him.

‘Coronation’

A criminal “coronation” would entail an elaborate ceremony of establishing someone into the ranks of professional criminals – i.e. “thieves-in-law” – a title acknowledged and respected throughout the criminal world in Russia. Before the Soviet Union collapsed, it was the only way for a person to be recognized as part of the top mafia echelon.

For most of the “thieves”, it began with a prison sentence. Although the era of wild capitalism and big money had loosened the unwritten rules compared to the Soviet period, serving a sentence was still considered to be the ‘right’ way to go about it. Nonetheless, there were rumors that ceremonies and titles were sometimes put up for sale for huge sums of money.

Under usual circumstances, however, officially joining the Russian mafia required time and effort. A convicted criminal who aspired to become a “thief-in-law” had to live an “honorable” life in confinement: i.e. not to cooperate with the prison officials and to undermine their authority by all means. He had to have powerful patrons among the current thieves who would vouch for him, too.

He would then position himself as stremyaschiysya, the term literally meaning “an aspiring [thief]”. News about the person’s “aspirations” would be spread throughout the country’s nationwide prison network, reaching the most distant places of confinement in Russia.

This was done for a reason: anybody who has ever witnessed an “aspiring” thief doing anything “inappropriate” (like cooperating with the police or receiving suspicious parole in the past) must immediately report it to the prison’s senior criminals, who would then pass the information further.

If nobody reported any damning information about the stremyaschiysya, he would then be summoned to a congregation of the most respected and influential thieves. The thieves would interview the aspiring thief about his past deeds: had he led any prison riot? Had he demonstratively disobeyed the prison guards? How much money had he collected for the obschak, the principal stash of illegal money of criminal syndicates?

The more despicable the informal ‘résumé’ of the candidate, the better. Such biography facts as service in the army, cooperation with the police, and drug use were considered to be serious offenses of the criminal code.

After everyone was satisfied by the candidate’s answers, the thieves would declare him to be their fellow thief in a ceremony called coronation. The ceremony was not nearly as graceful as the name suggests and there was no physical crown present. The congregation simply announced that the man was now “one of them”, and the crowd would disperse. At this moment, a new member of the mafia – a new “thief-in-law” – would be “born”.

Rules of the game

After the coronation, the newly made thief would swear to renounce any legitimate lifestyle once and for all: he must not work for anyone, he must not earn money by legitimate means, he must not serve in the army and he must not cooperate with legitimate authorities.

In return, vory would receive privileges not available to common criminals. “They thought of each other as brothers and peers. They would support each other, they were honest with each other, and they would watch each other’s backs,” writes a police colonel turned writer Sergey Dyshev.

The fall of the Soviet Union altered the game, however. Long after the Gulag, it was the wild lawless capitalism of the 1990s that changed thieves, once again.

‘Wild 90s’

Former peers turned on each other as they began dividing spheres of influence. Even their outlook changed.

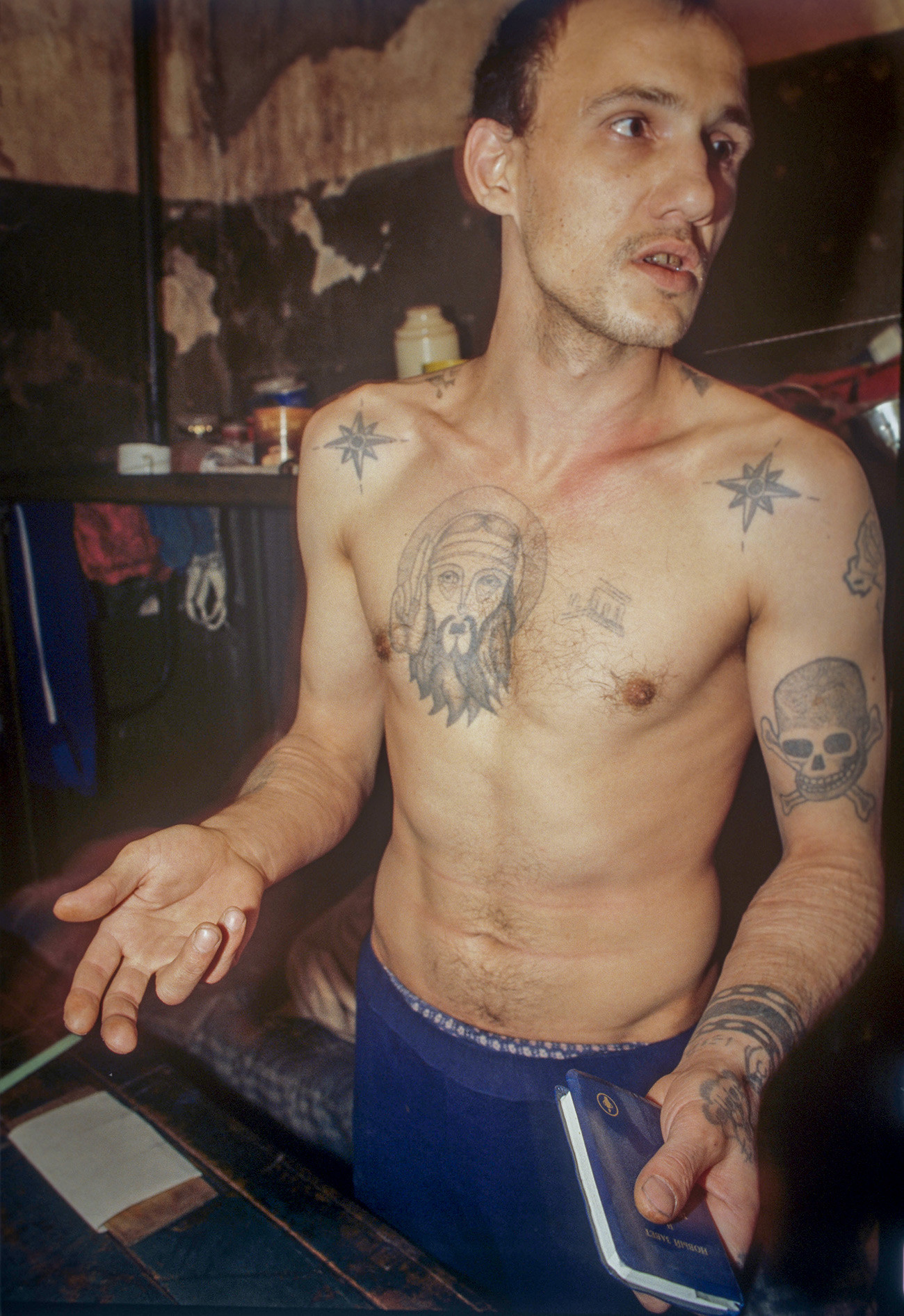

“[Today], they no longer separate themselves from the mainstream, they eschew the tattoos that openly branded them as members of the vorovskoy mir [thieves’ world],” wrote Mark Galeotti, a scholar who studied the Russian mafia.

Their solemn oath to refrain from earning their living by legitimate means all but disappeared, too. Those who had enough power and influence set out to build criminal empires that would flourish in the 1990s and penetrate all spheres of the country’s economy.

One thief-in-law, Shurik Zakhar, known for his fierce wars with the Chechen and Georgian mafia bosses in the Russian capital, invested in alcohol retail and car dealing businesses.

Another thief, Pavel Zakharov, who shipped cocaine from Columbia to Russia, reportedly defended the new way of doing business: “The obschak [stash of illegal money] is great, but thieves need a solid financial base to be relevant these days and such a base can be built by criminal bosses who invest in legitimate business.”

Especially powerful and resourceful thieves constituted a substantial part of the national economy at some point. Ded Khasan’s criminal empire reportedly had shares in banks, casinos, hotels, markets, restaurants, and other major businesses throughout Russia, the CIS, and even Europe.

The end of thieves

Yet the most radical change that eventually put many thieves out of business, came down to erosion of reverence the vory once had for their peers. Before the 1990s, lynching a “crowned” thief without a prior approval of the rest of the thief community would result in a death of the culprit. The 1990s turned everything upside down. The former untouchables were blown up in their cars and hit by bullets so often that the incidents no longer surprised anyone.

“Conflicts among these people happen for two reasons: struggle for power and money. There is no other reason,” said Alexander Gurov, general-lieutenant of the police and a professor, in one interview.

On a winter day in January 2013, one of the most influential thieves in law at the time, Ded Khasan, was walking to his clandestine office, located in a restaurant, in the center of Moscow. He didn’t hear the shots, as the killer fired with a ‘Val’, a Russian-made silent rifle. A bullet hit Khasan in the head and he died, leaving his criminal empire, and his mortal coil, behind.

Click here to see 10 favorite cars of the Russian mafia.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox