How little Russian tsars were raised

Messengers are being sent to all Russian towns from the Moscow Kremlin, alms are being given out in the name of the tsar to churches and monasteries, and petty crimes are being pardoned. Meanwhile, officials from every town are getting their horses ready to ride to Moscow and bring presents.

If all this is happening, it means a child has been born in the family of the Moscow tsar. But what’s next? What are the steps to raise an autocratic sovereign?

Home is where the Kremlin is

The tsarina's main chamber in the women's quarters of the tsar's palace (contemporary reconstruction in Kolomenskoe, Moscow)

Legion MediaUntil they were 5, both daughters and sons of the tsar and tsarina would live in the women’s’ quarter of the palace, supervised by a little army of wet nurses, nannies, and housemaids. The tsarina, the mother, could play with her child as much as she wanted, but raising the baby, replacing its diapers, feeding it and putting it to sleep – was the servants’ responsibility.

So, why keep the toddler in private rooms until he/she was 5? Because the Russian tsars were highly superstitious and afraid of black magic. As historian Vera Bokova writes in her book, ‘Childhood in the home of the Tsar’, the midwife who accepted the baby was one of the foremost servants who would care for the baby: she knew everything related to the baby’s health, and, in the absence of professional doctors, was the main authority in medicinal matters – and magical ones, too. The midwife saw to it that the moonlight wouldn’t fall onto the baby’s cradle (for a good night’s sleep), and protected it from the evil eye: she made sure that nobody would look at the baby while it was asleep, would smear soot behind his/her ear and would sprinkle some salt near the baby’s head every day.

Peter the Great as a child

Archive photoUntil 5 years of age, only close relatives and servants could see the tsar’s children. If they went to church, servants would carry woolen curtains on either side of the children. The children traveled in carriages with windows curtained shut, and the yard they played in was closed. However, the tsar’s children had their own playmates: children from wealthy families who were allowed to play with little tsars.

Little tsars: majestically fat & slow

Alexey Alexeevich of Russia (1654-1670)

Archive photoRussian tsars never ate cabbage. It was considered ‘peasant food’, and indeed, was the most frequent dish on a Russian peasant’s table. Meanwhile, pickled cabbage contained a lot of vitamin C, essential for health. It’s no wonder the first Romanovs suffered from scurvy (a disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin C, characterized by swollen bleeding gums and the opening of previously healed wounds). But tsar babies were fed abundantly. If a baby started crying, it immediately received a handful of cakes, sweets, nuts, etc. Tsar children were fed 5 times a day, and in between always had unlimited access to snacks.

So this is why all Russian tsars and tsarinas were so plump. Russians were also sure that austere and strict talks were harmful to a child’s development, so tsar nannies talked to their little superiors only in a sweet, ingratiating tone, using a lot of diminutives. And, of course, little tsars and tsarinas were never punished, only lightly reprimanded.

But kids are kids, and they all love toys. Even grown-ups would envy the abundance of toys Russian tsars had as kids. Toy houses, spinning tops, chess, checkers, European mechanical toys: music boxes, wind-up birds and soldiers; musical instruments: from simple bugles to royally decorated clavichords. A special place in the boys’ rooms was reserved for military toys: bows and arrows, miniature military colors, axes, knives, pistols, carbines, hand bombards, sabres and swords.

Miniature from Pyotr Krekshin's book "Life of Peter the Great." Peter the Great in his youth, commanding his regiments.

SputnikThe ultimate toy was the toy horse that every boy in the tsar’s family had. But Peter the Great had even more – as a kid, he was given a full miniature carriage pulled by four ponies. And instead of toy soldiers, he had midget servants dressed up as royal guards – a little army, indeed!

Peter’s father, Alexis of Russia, was also entertained a lot as a kid: men would fight bears for his pleasure and he would watch performances of court jesters and jokers. At the age of 7, he learned chess, and by 8, he learned to shoot a bow. But military exercises were already a part of another life that only began after the children moved from the women’s quarter to their own rooms.

‘Fearsome punishment awaits those children’

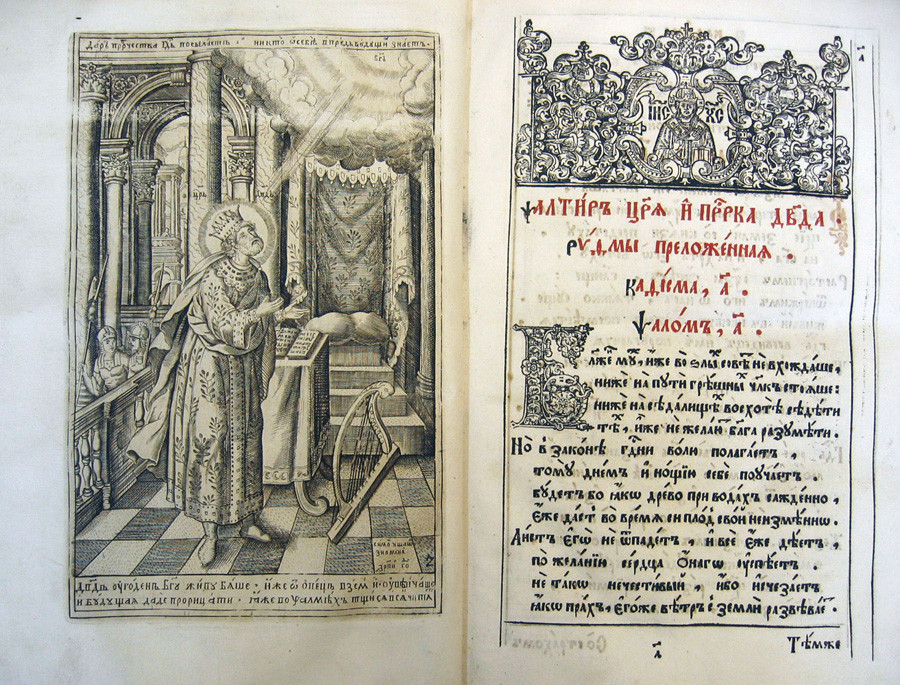

Book of Psalms, 17th century

Archive photoFor the tsar’s daughters, their whole life was to be spent in seclusion – after the age of 5, they would stay in the women’s quarters of the palace, which they rarely left. But the boys started a completely different life. All nannies and nurses ceased their care, and boys started living in the men’s quarter under the supervision of a tutor – usually a respected boyar.

The tutor’s mission was to teach the boy how to read, write, ride a horse and behave aristocratically. Russian tsars were to behave in a way that ruled out any possibility of mocking them. So little tsars were taught to walk and move slowly, majestically, without any kind of hurry.

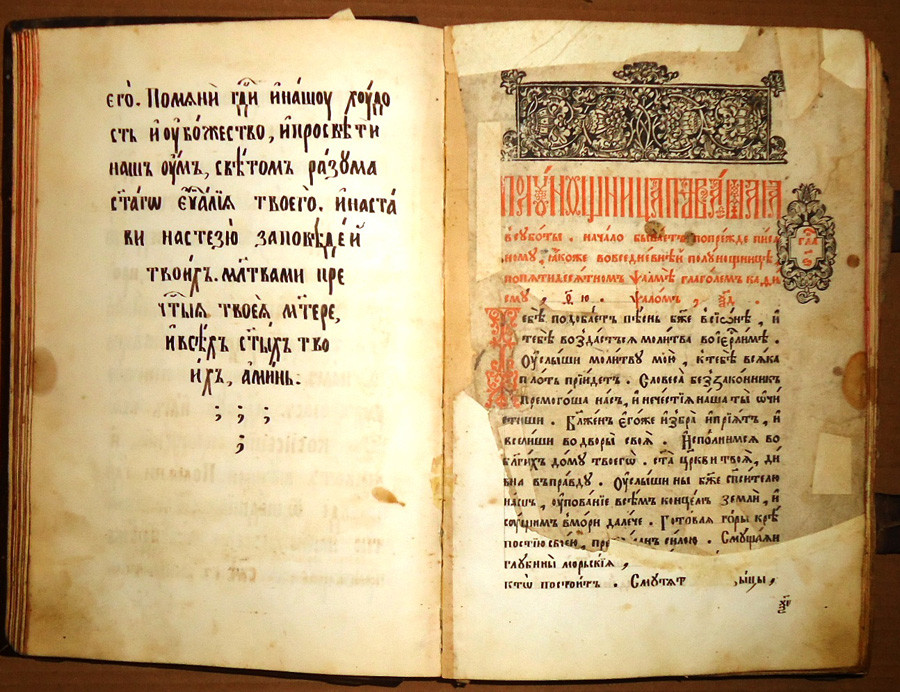

Book of Hours, 17th century

Archive photoThe tutor would become the only person that could punish the royal children. The upbringing in those times was based on Christian literature, for example, St. John Chrysostom, who wrote: “Fearsome punishment awaits those children who do not submit to the authority of their parents.” Birch rods, used for corporal punishment, awaited the royal child for bad studying, laziness, and disobedience. A harsh change from recent sweet talks of nannies and nurses.

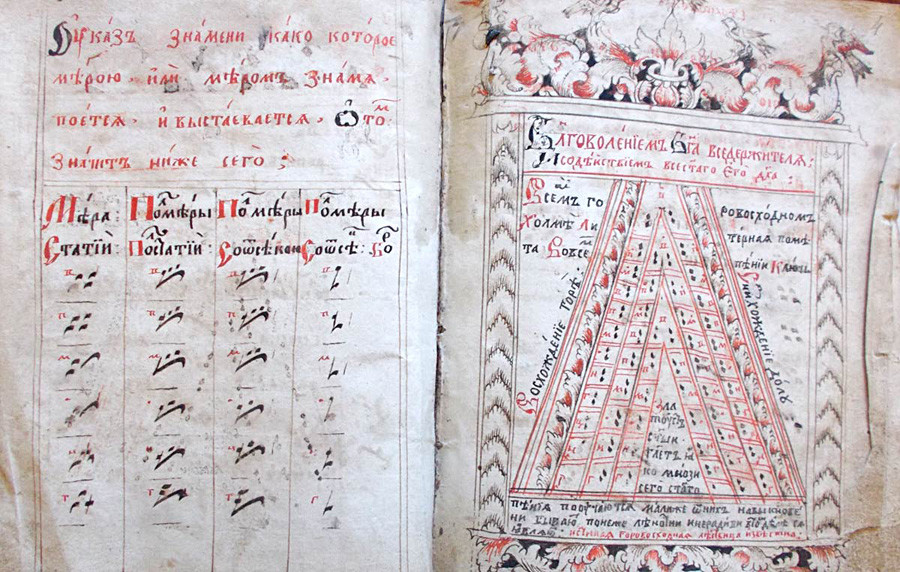

17th-century book of melodic notation for liturgical singing

Tomsk Local MuseumSo what did they study? Only a few of contemporary schoolchildren could ever master the little tsar’s program. The main method was studying by heart. When the kid could already read, he started learning excerpts from religious literature. The Book of Psalms (150 religious hymns). The Book of Hours (prayers and church service for every day). The Book of Acts. The New Testament. Also, different compilations of religious hymns. So, the reading circle of young tsars was really impressive. Writing started at about 8, and at the same time, boys were taught to read notes and sing religious hymns, which continued for another 2 or 3 years. When the boy turned 16, he was considered to have come of age and the search for a bride would begin.

Was this royal education useful?

'Nikita Zotov teaches Peter the Great fortification and military affairs' from Pyotr Krekshin's book "Life of Peter the Great."

SputnikSo, they were brought up as little theologians and little warriors at the same time. They could be military commanders and take part in religious discussions. But was it exactly what the sovereigns needed?

Obviously, no. Little tsars weren’t taught economics, foreign languages, military strategy and many other things necessary in a changing world. And the end of this “traditional” upbringing came about in the middle of the 17th century. Alexis of Russia, Peter the Great’s father, was the first tsar who started to include some elements of European education into the upbringing of his children. His first son, Alexei Alexeyevich (1654-1670), was taught Latin, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and even learned poetry.

However, Peter went even further. He also learned hymns and the New Testament – but he always did what he wanted. So, when he was 12, he ordered different instruments and machines to be brought to his palace. Physical labor was considered “unbecoming” for the tsar – but Peter learned how to chisel stone, how to print and bind books, he learned to carve wood and sail ships. A new epoch was coming, one where even the tsar needed some form of professionalism. Under Peter’s reign, the old order of palace life remained only in the women’s quarters of palaces in Moscow, and waned away by the middle of the 18th century.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox