The WEIRDEST medicine Russian tsars used

Russian tsars were devoted and true Orthodox Christians, so for them, any medicine offered by a Protestant or a Catholic was eyed with caution. Even in case of real danger, tsars would first ask for help from locals. We took a look at the strangest medicines Russian tsars applied to themselves.

Bloodletting – using birds of prey

Venesection, or phlebotomy, was one of the most common medical practices performed by surgeons from antiquity until the late 19th century, a span of over 2,000 years. In the absence of other treatments for hypertension, bloodletting was popular as a method that temporarily calmed patients and made them feel better.

The first recorded bloodletting on a tsar was done for Mikhail Fyodorovich (1596 – 1645), the first Romanov. His son, Alexis of Russia (1629 – 1676), was an avid falcon hunter, so bloodletting for him was performed in the strangest fashion: by a falcon who was placed on the tsar’s arm and “opened the blood” with a hit of his beak.

Alexis demanded his boyars to perform bloodletting with him. German traveler Augustin Meyerberg described that one time, when a nobleman Rodion Streshnev tried to refuse (reasoning that he was old and weak), Alexis slapped him on the face and kicked his behind, screaming: “Worthless slave, are you taking your sovereign for nothing? Could it be that your blood is more worthy than mine is?” Streshnev had to comply.

Gems – Ivan the Terrible’s infatuation

'Ivan the Terrible Showing Treasures to the English Ambassador Jerome Horsey,' 1875, by Alexander Litovchenko

Alexander Litovchenko/The Mikhailovsky PalaceMoscow tsar Ivan the Terrible (1530 – 1584) believed in the healing power of gems. Ivan the Terrible’s panagia (a medallion with an icon, worn around the neck) contained ‘healing’ pieces of pearl and sapphire. Jerome Horsey, an English diplomat on a mission to Moscow, described Ivan the Terrible showing him his gems and telling about their powers.

“He placed a red coral and a turquoise stone on his arm; and the wretched man pointed to their change of colour as the effect of the disease which poisoned his blood, and which accordingly would prove fatal. ‘The diamond restrains fury and luxury,’” Horsey reports Ivan as saying. “‘The ruby is most comfortable to the heart, brain, vigor, and memory of a man. The emerald has the nature of the rainbow; this precious stone is an enemy to uncleanliness. The sapphire I [find a] great delight in; it preserves and increases courage, joys the heart. All these are God’s wonderful gifts, secrets in nature, and yet [God] reveals them to man’s use and contemplation, as friends to grace and virtue and enemies to vice.’”

Alcohol – first vodka in Russia was sold in a drugstore

At first, high alcoholic spirits appeared in Russia as a kind of medicine. Around the 14th-15th centuries, a kind of ‘vodka’ was presented to one of the Moscow princes by European merchants. The very word ‘vodka’ in the Russian language appeared first at the beginning of the 16th century and meant a high-spirit alcohol herb tincture. Possibly during the same epoch, the tsar’s servants began producing small amounts of spirits distilled from European wines. These ‘vodkas’ were sold in a drugstore on Moscow’s Red Square and could be purchased only by the most wealthy Muscovites, because they cost a fortune.

Wines were also used as a remedy: to warm up the body and provoke sweating. When Mikhail Fyodorovich lay dying, his doctor tried to “clean his liver” using warmed-up rheinwein (hock). But the tsar died anyway.

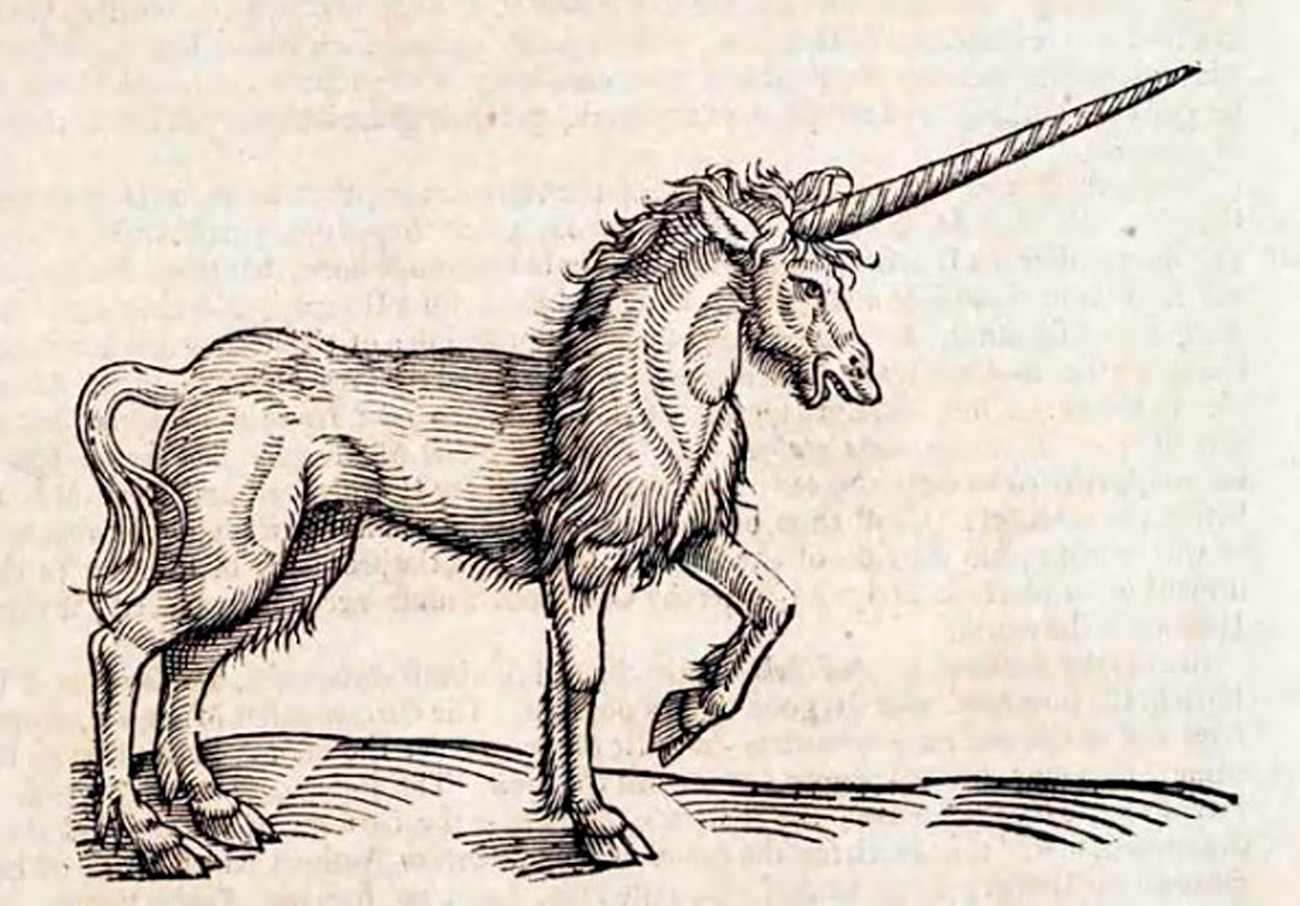

Unicorn’s horn – ‘tested’ with pigeons

In the Middle Ages, a belief existed that unicorns grazed the lands that were never visited by a man. For early Russian tsars, the unicorn was a symbol of sacral, spiritual power. It was used on Ivan the Terrible’s royal seal. Texts about the miraculous power of unicorns and their horns had circulated in Russia even earlier than the 16th century, and Ivan the Terrible had a staff made out of ‘unicorn’s horn’ that, most likely, was just a narwhal whale’s tusk.

The ‘unicorn’s horn’ (and powder after grinding it) was believed to be a universal antidote. In 1654, Alexis of Russia ordered a horn from Lübeck, Germany. Next year, the tsar was offered three horns for 11,000 rubles. The horn was almost 50 times (!) more expensive than gold at the time.

And how was the expertise carried out? Dr. Clare Griffin, a researcher from the University of Cambridge, writes that pigeons were used for poison testing in the Moscow tsar’s chambers. One pigeon was fed arsenic, the second one – arsenic and horn powder, and the third one – horn powder and arsenic after that. The first time, all three pigeons lived; after repeating, only the third one survived – this proved the ‘authenticity’ of the horn. But in 1669, the tsar’s doctors refused to use a horn after doing their own research – they actually found out it belonged to a narwhal whale, the “sea unicorn”. In the 18th century, obsolete medicinal beliefs slowly started to drift away.

Arsenic

Arsenic

Raike (CC BY-SA 3.0)Ivan the Terrible waged a war against the ancient Russian aristocracy – Rurikid princes and boyars who were plotting to depose him from the throne. Ivan actively used poisons. In 1570, he invited German physician Eliseus Bomelius to prepare poisons for killing his enemies. But, afraid of being poisoned himself, Ivan daily took small amounts of arsenic, the most common and easily obtained poison of the time, to develop resistance to it and withstand a possible poisoning.

Moscow tsars in the 16th-17th centuries had a rule that each and every dish they ate had to be first tested by their servants, and if a doctor prepared medicine for the tsar, the doctor always drank several times the amount of the medicine the tsar took – so it would be harder to poison the sovereign. However, a chemical investigation carried out on Ivan’s body in 1965 showed the tsar had died of mercury poisoning.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox