The PAIN of ancient Russian dentistry

“Against weak gums and bleeding teeth, wobbly teeth, bad breath, and against all other dental grievances, mix the powdered horn of a deer with wine, then lather it around the loose tooth, and it will stop wobbling”.

Such were the recipes against toothache supposedly created by Eupraxia (?-1131), the granddaughter of Vladimir Monomakh (1053-1125), Prince of Kiev. If there was such a woman as Eupraxia (also known as Zoe and Irene) she was probably the first Russian-born woman medic. Her nickname was “Добродея” (Dobrodeya, ‘Do-Gooder’). After she married Alexios Komnenos, the eldest son and co-emperor of Byzantine emperor John II Komnenos , there in Byzantium, she created a treatise, entitled "Ointments" that is regarded as the first treatise on medicine written by a woman. The recipe above is taken from her book. Although we have to admit, historians are not yet sure if this person actually existed. For years to come, Russian people didn’t have proper dentists and used such recipes, or medicine prepared by witch doctors.

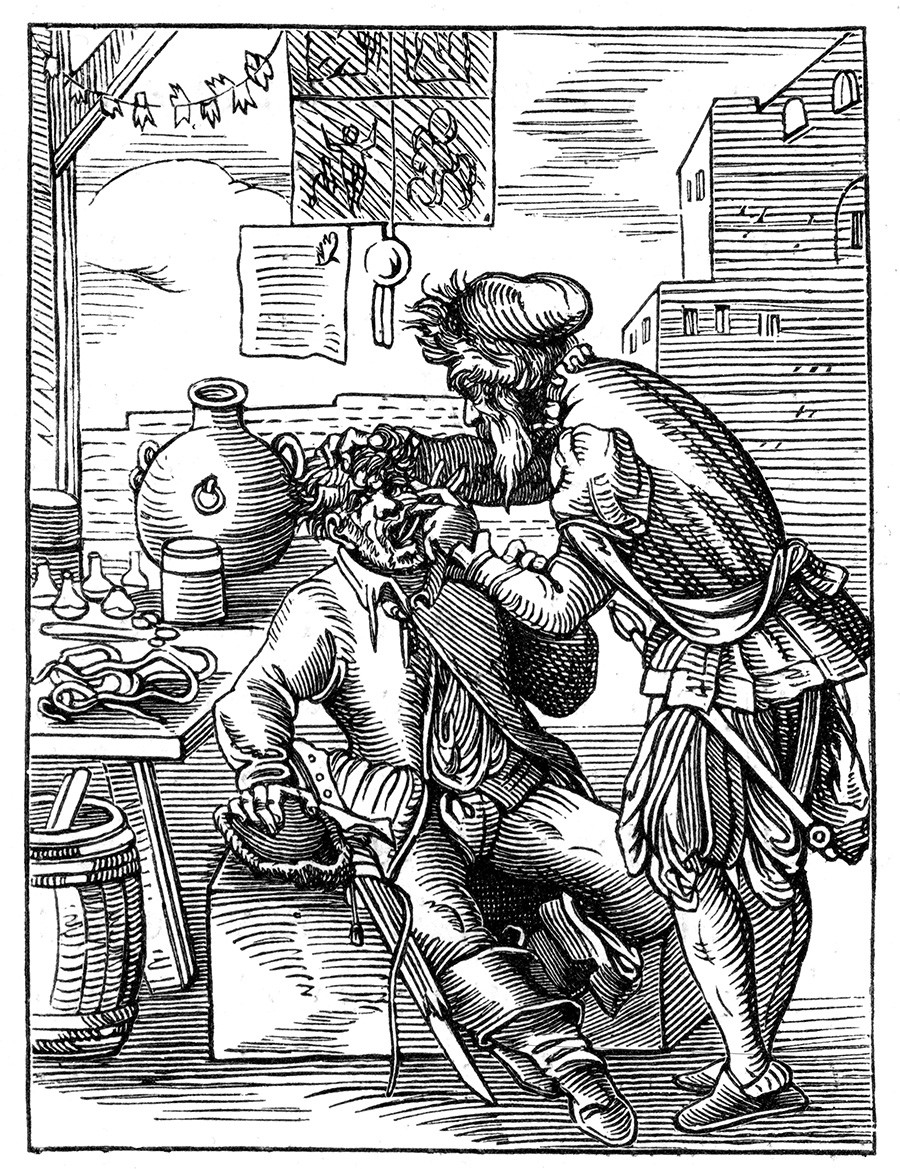

Dentist, 16th century

Getty ImagesThe first official government permission to practice as a dentist in Russia was given out in 1710 to François Dubrel. It’s no coincidence that this happened under Peter the Great – the tsar loved to pull teeth himself, and it’s also typical that Dubrel wasn’t Russian. The first dentists in the country were foreign. Slowly during the 18th century, some Russians also started doing dental surgery, but there weren’t many of them: about 24 in 1811, and 26 in 1844. The first private dental school opened only in 1881. Let’s see how the Russians treated their teeth in ancient times.

Honey, oak, horseradish

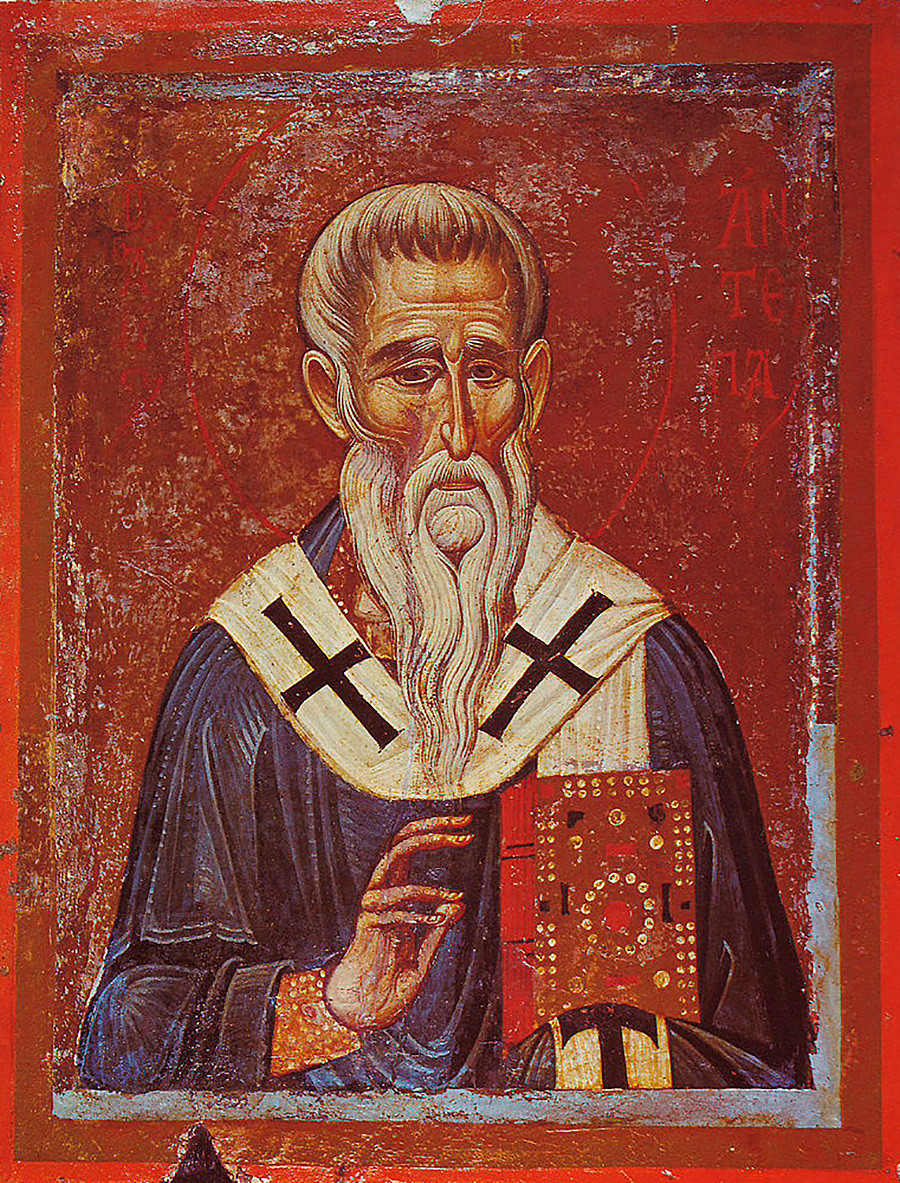

St Antipas Icon, 13th century

Public domainMedieval Russians had a few options if they had a toothache: go to a foreign medicine man (probably a Greek one), visit a witch doctor, or go to church.

Saint Antipas of Pergamum was the Christian saint ‘assigned’ to toothache. He is revered as the patron saint of dentists, and Russian people prayed to Antipas when they had toothache. Even tsars Ivan the Terrible and Alexis of Russia made rich contributions to the church of Saint Antipas, built in the 16th century near the Moscow Kremlin.

Foreign medics weren’t available to anyone but the tsars and boyars (the only ones who could afford them). So, for simple folk, church or witch healers were the only available choices. The most popular way of treating toothache was spells; here are some of them.

St. Antipas' church in Moscow

Public domain“How this strawberry withers and dries, may the teeth of God’s servant dry out and become insensitive,” or “Come down, moon, and take away my toothache, take it as far away as the clouds,” and so on.

Surely, potions and self-made medicine were also used, oak being the most frequently used remedy. Witch doctors advised peasants suffering from toothache to gnaw on oak bark or drink oak bark tinctures. This was quite useful, actually: oak bark contains tannin that has antiseptic qualities.

Ancient medical texts also contained various recipes to heal toothaches and various diseases of the mouth. Honey and horseradish were used against stomatitis (inflammation of the lips), alums (sulfate salts) and saltpeter used for antiseptic purposes.

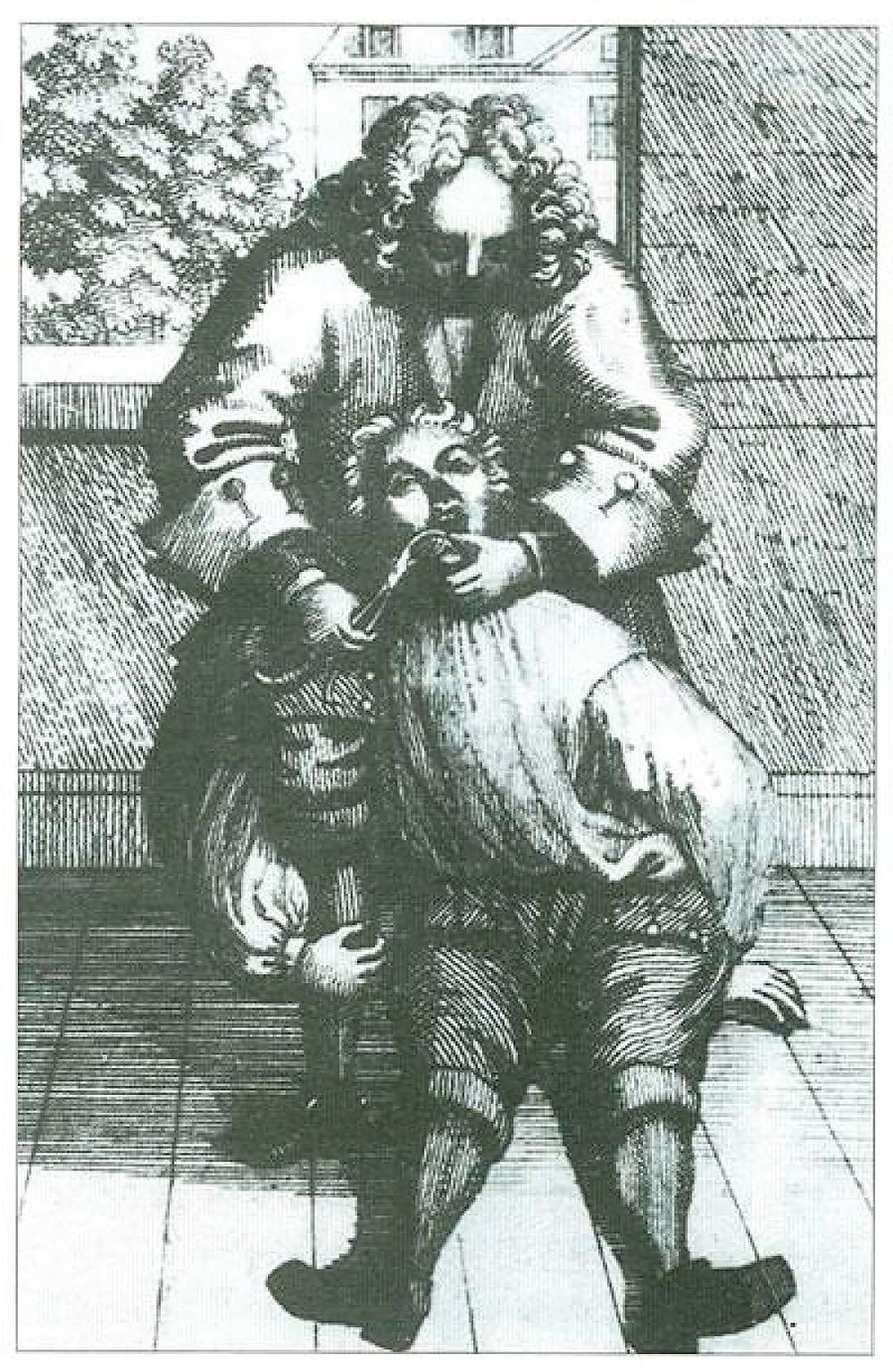

Before the dentist's chairs appeared, dental operations were usually performed on patients seated on the floor

Public domainAll these potions were necessary, because an ancient Russian would do literally anything to evade being operated on. Obviously, there were no painkillers, so any operation became excruciatingly painful, and more to it, there were no doctors that could successfully perform such operations. Only tsars and grand princes had access to professional dental help.

Dentists of the tsar

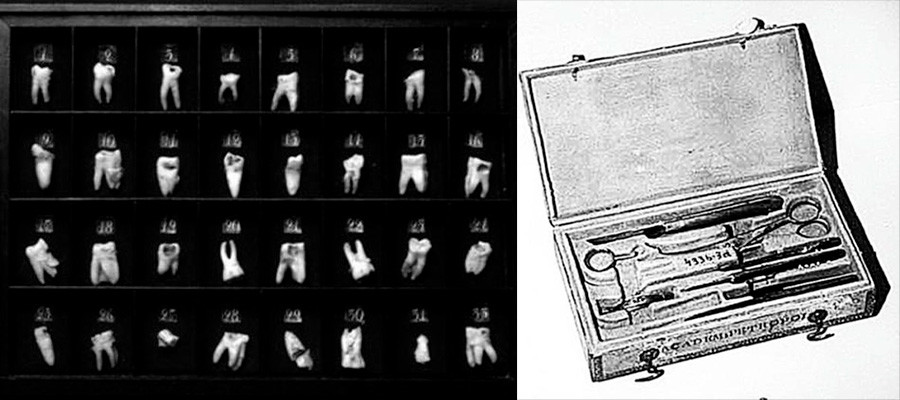

The collection of teeth pulled by Peter the Great, and a dentist's toolbox of the 18th century.

KunstkameraAfter Byzantine princess, Zoe Paleolog (named Sophia in Russia) became the wife of Ivan the Great, Grand Prince of All Rus’, the Moscow court has elevated to new heights, including medical ones. A German doctor named Anton lived by Ivan’s court in the 1480s, a Jewish doctor named Leon, from Venice, was known in Moscow in the 1490s. By the 16th century, a foreign doctor (most often, an English one) was usually to be found in the Moscow court. Studying Sophia Paleolog’s remains, anthropologists note that in 1503, when Sophia died, she was about 50-60 years old and had all but six of her own teeth, with only one dental cavity. Incredible!

Recipes against toothache appeared in the 16th century “Domostroy,” a set of household rules and instructions. It recommended pickled cabbage against weak gums (effective!), celery tincture for cleaning the mouth (useful!), and other quite rational recipes. It is widely believed that “Domostroy” was written by Sylvester, Ivan the Terrible’s spiritual mentor.

The remains of Ivan the Terrible, photo taken in 1963. Notice the teeth still intact.

Moscow KremlinAnd Ivan himself had very good teeth, which can be clearly seen in a photo of the tsar’s remains. At 53, his health suffered a major blow due to long-term mercury poisoning (most likely, Ivan was secretly fed mercury by his foes, which caused his death), but his teeth were mostly intact. That said, let’s remember that mercury was widely used in 16th and 17th century Moscow for making the teeth white – and it had devastating consequences.

Black teeth beauty

An ancient dentist's instrument.

“Sugar-white teeth” were very often featured in the descriptions of Russian beauties of the 17th century left by foreigners. But for such teeth, noblewomen paid a high price. Teeth could be whitened with mercury. This was usually done while the woman was looking for a husband, to smother the poor guy with divine beauty; but mercury-whitened teeth slowly lost their enamel and became disgusting and grey.

To hide the ugly stumps of teeth, women blackened them with soot, so if you saw a beauty with shiny white teeth, she most likely was newlywed or looking for a husband; married women had black teeth. Ugh!

This ‘fashion’ didn’t last long, because the health drawbacks quickly became obvious; however, in the Russian countryside, merchants’ wives blackened their teeth in the 18th century as well. Professional dental help in the Russian countryside was (almost) non-existent until the late 19th century.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox