How the USSR created the world's best sanitary-epidemiological service

The Soviet regime inherited a sorry legacy from the Russian Empire in terms of infectious diseases. In 1912, for instance, around 13 million people were identified as carrying one — as much as 7% of the total population.

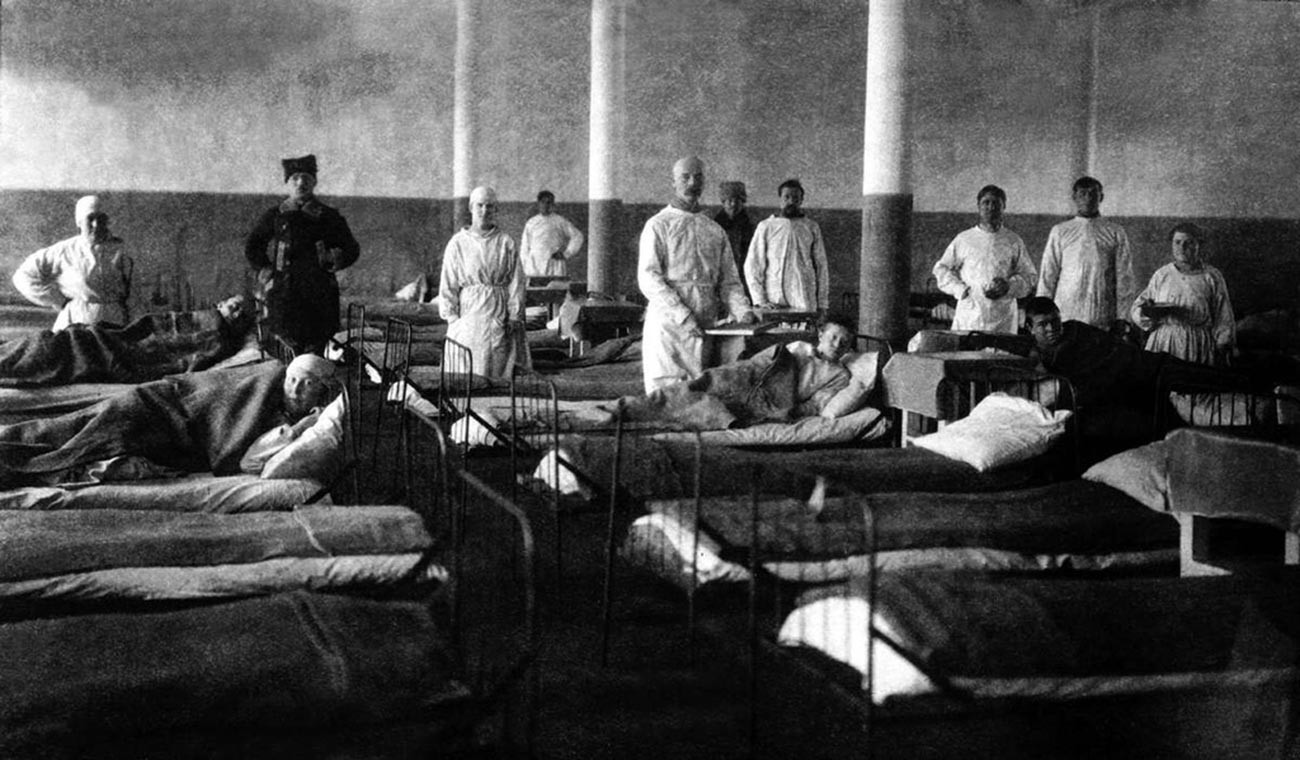

Despite the fact that public health organizations had been set up in dozens of pre-revolutionary Russian cities, there was no single nationwide sanitary-epidemiological (SANEPID) service. The situation was significantly worsened by World War I and the Russian Civil War.

On coming to power, the Bolsheviks became acutely aware of the problem: the Spanish flu was raging throughout the country, not to mention the traditional cholera and typhoid. Despite serious economic difficulties, the authorities nonetheless allocated large amounts of money to improve health conditions in settled areas and encourage the population to take previously unheard-of health precautions.

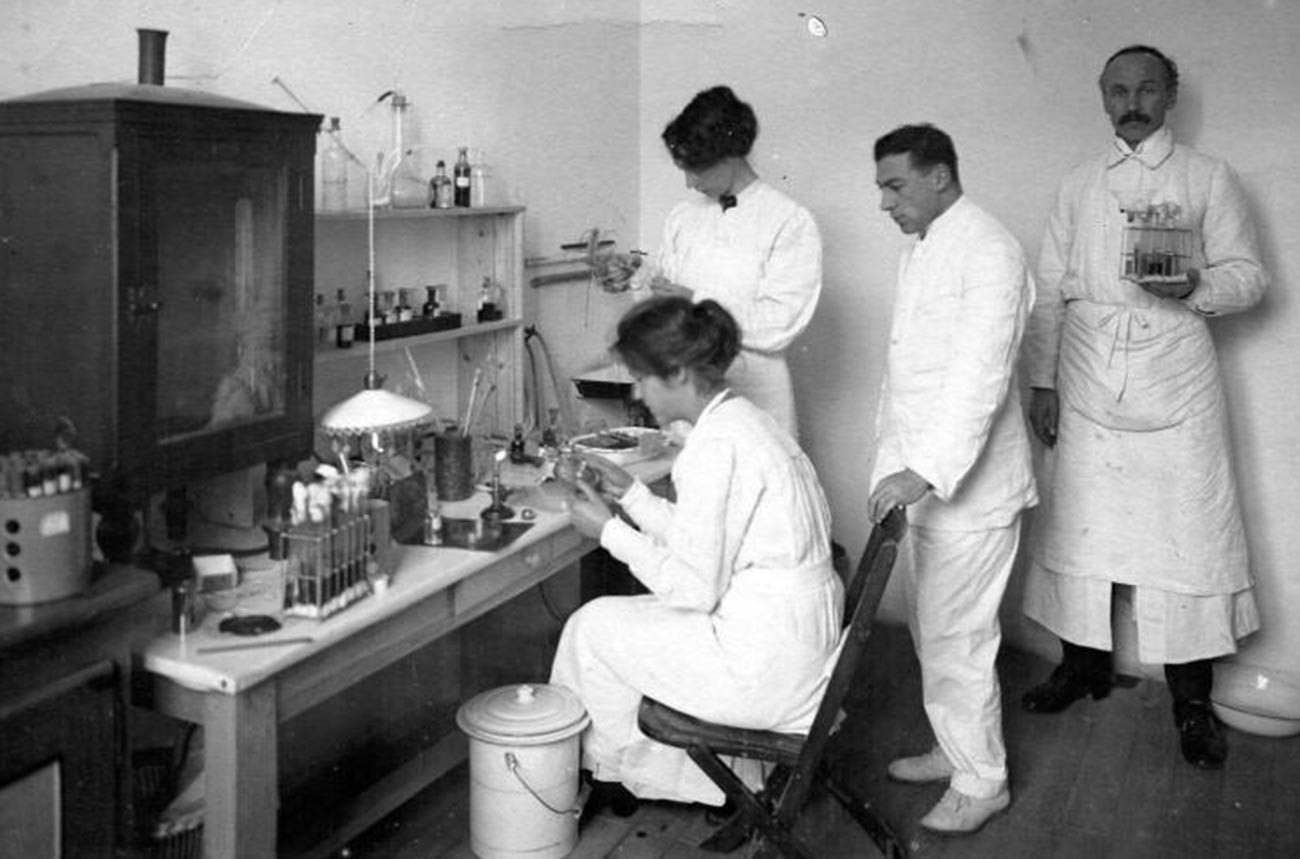

The adoption of a public health decree on Sept. 15, 1922, introduced a single public health organization, and SANEPID stations began to crop up offering everything needed to fight infectious diseases, including laboratories. This date is considered the birthday of Russia’s SANEPID service.

Realizing that prevention was better than a cure, the authorities introduced far-reaching preventive sanitary measures, including for the food industry and public catering. Already by the late 1920s, mortality rates, including among children, and the incidence of infectious diseases had declined significantly.

At the same time, the Soviet Union paid a great deal of attention to the training of future epidemiologists, microbiologists, and infectious disease specialists. The early 1930s saw the opening of the first sanitary-hygienic departments at medical institutes.

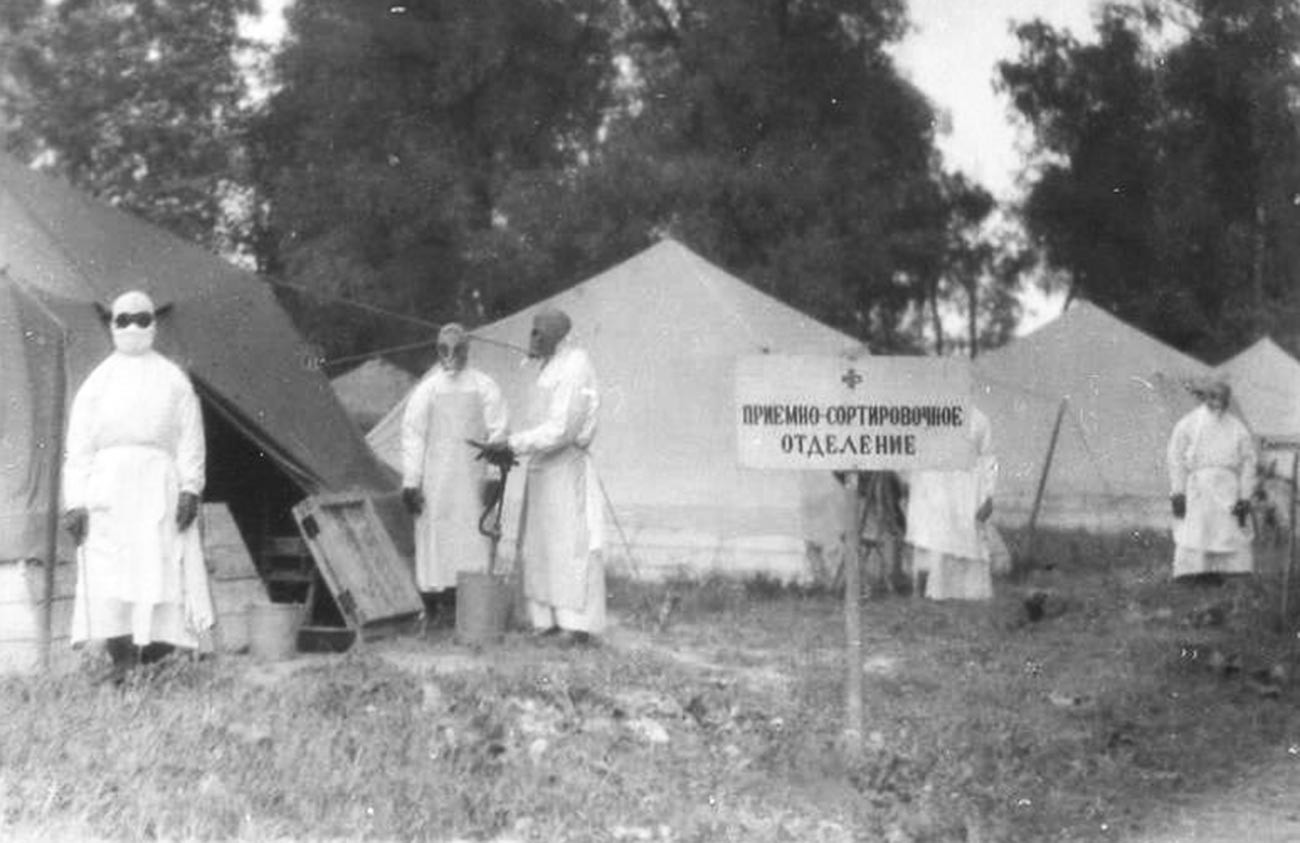

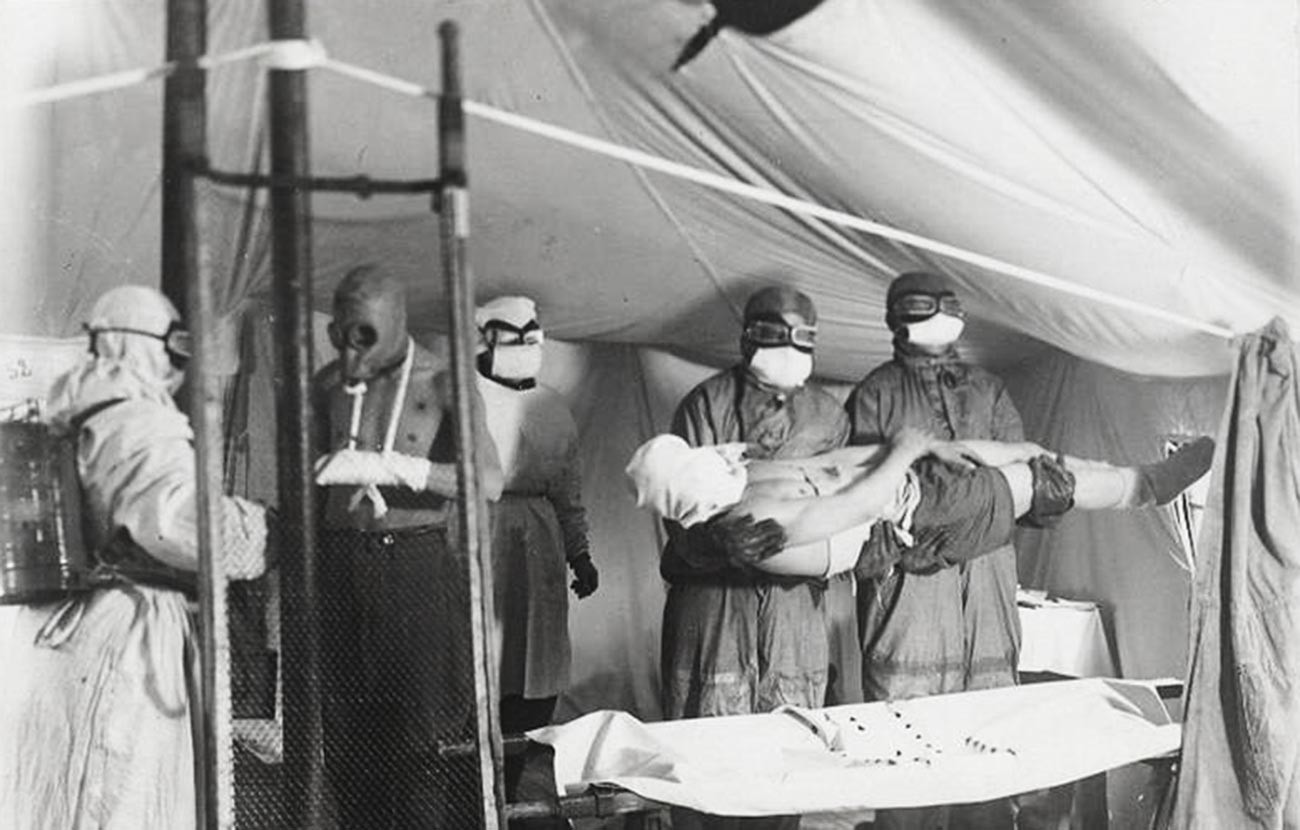

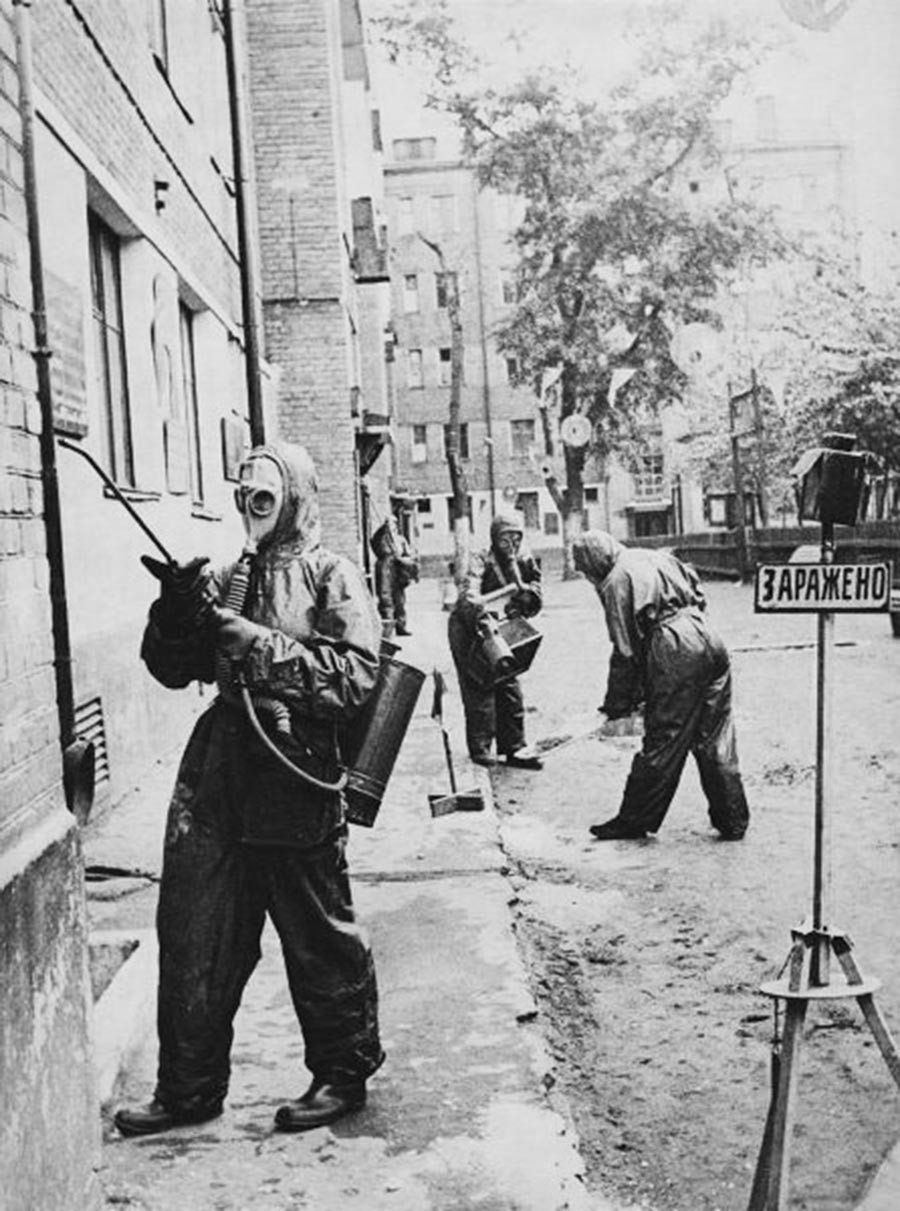

World War II caused the migration of huge swathes of the population and the devastation of vast territories, which led to a serious deterioration of the epidemic situation in the USSR. Dysentery, malaria, typhus, and viral hepatitis proliferated throughout the country. To remedy the situation, SANEPID squads, isolation hospitals, and disinfection units were established as a matter of extreme priority. Training soldiers in the rules of personal hygiene played a key role in tackling the problem.

In the post-war period, the SANEPID service developed alongside industry in general. This resulted in the appearance of a new branch known as “radiation hygiene” — aimed at controlling and reducing workers’ exposure to ionizing radiation at factories and enterprises.

In the early 1970s, the SANEPID service of the USSR was granted broad powers to combat environmental pollution and infectious diseases. No industrial enterprise could be put into operation without one-site treatment facilities, and no settlement could be built without observing the sanitary rules. Sanitary inspectors’ instructions had to be implemented unquestioningly by all state and public institutions, as well as ordinary citizens.

In addition, enterprises, organizations, departments, and even ministries were ordered to comply with all sanitary and hygiene regulations, or else face disciplinary, administrative, and sometimes even criminal liability.

Over the two decades from the 1950s to 1970, the incidence of typhoid fever in the USSR decreased almost fourfold, whooping cough eightfold, and diphtheria more than 70-fold. Vaccines against measles, mumps, polio, and flu were developed and introduced into public health practice. An effective vaccination system was set up nationwide.

It is to the Soviet Union’s immeasurable credit that one of the most terrible diseases known to humankind, smallpox, has been extinct in the wild since 1980. Back in 1958, it handed over 25 million doses of a specially developed vaccine to the WHO for use worldwide, including in India, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and Burma. The Soviet Union donated more anti-smallpox vaccines to the WHO than all other countries combined.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox