The most successful Soviet intelligence operation during World War II

One cold winter night in 1941, German positions under Mozhaysk, in the Moscow region, were approached by a man - a traitor, claiming to represent an anti-bolshevik church and monarchy-sympathizing group called ‘Престол’ (“Prestol”; Eng. “throne”). He was willing to assist the Germans in bringing down Soviet rule.

In reality, the man was a Soviet intelligence agent named Aleksandr Demyanov. One of the most successful intelligence operations in the history of the USSR had now entered its active phase. The operation’s name was ‘Монастырь’ (“Monastyr”; Eng. “monastery”).

An ideal candidate

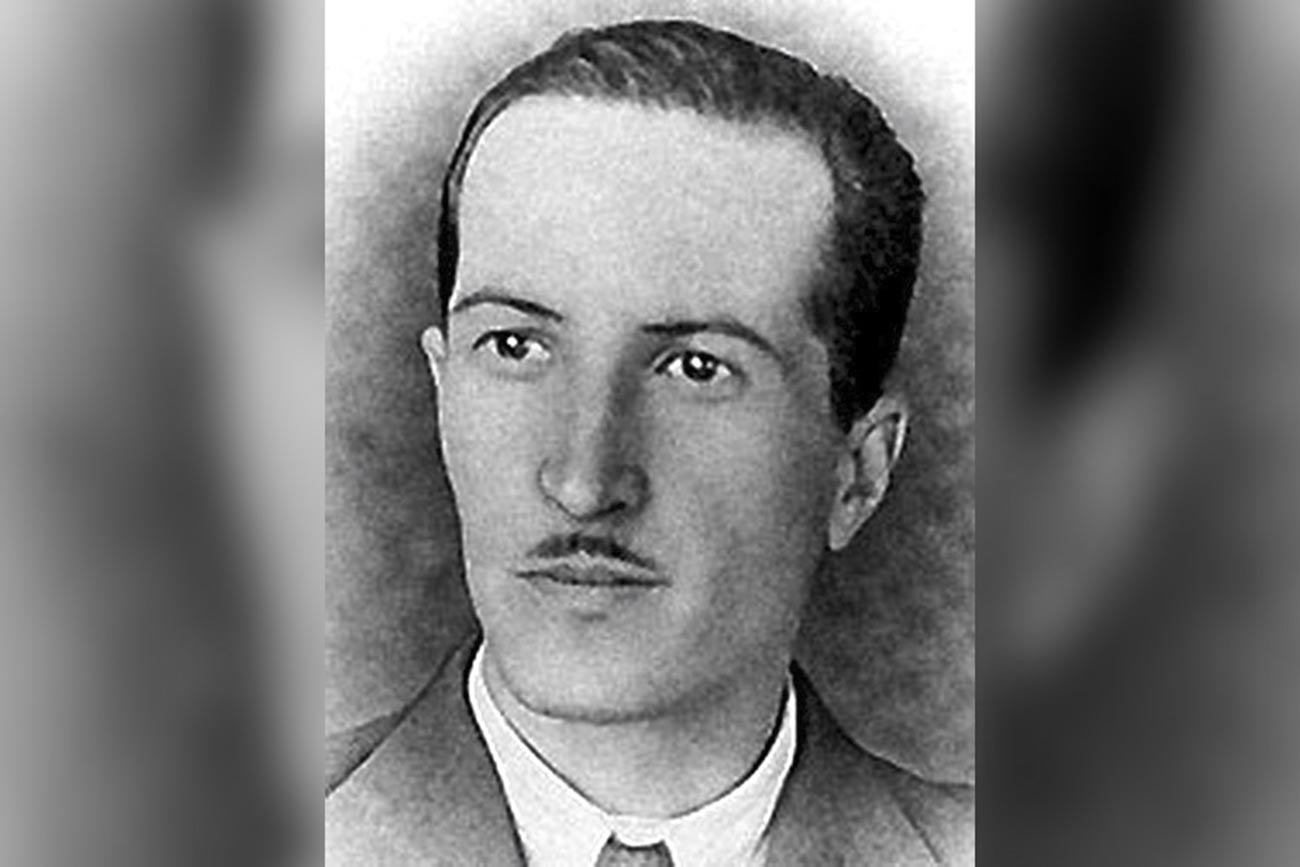

Sporting oodles of charm, intelligence and good education, with an excellent command of German, Aleksandr was a perfect fit for deployment behind enemy lines. Not many in Moscow had a clue that the man who came from noble beginnings had already been turned by Soviet intelligence some time at the beginning of the 1930s.

Alexander Demyanov

Ministry of Denfese of the Russian FederationThe spy had a good story. His mother and grandfather were local celebrities in White-affiliated immigrant circles in Germany, while other relatives had been living in Third Reich-friendly Italy. Besides that, Demyanov - alias ‘Heine’ - was a regular face at embassy functions in Moscow, often in the sight of foreign intelligence.

In July 1941, the Soviet intelligence service created the fictitious Prestol, supposedly a ragtag band of underground monarchy sympathizers, awaiting the arrival of German troops in the Soviet capital.

Back in the USSR

According to the initial gameplan for Monastyr, Demyanov was to be sent to Berlin, where he would infiltrate the circle of White Russian immigrants working with Germany, as well as establish his own solid contacts inside the German intelligence apparatus.

However, things don’t always go as planned. Following lengthy and thorough checks (Demyanov was even put in front of a firing squad for added effect), the Germans decided, after all, to use the Russian as their mole in the USSR.

After several months of training at Abwehr, the Third Reich’s military intelligence school, and given a brand new alias - ‘Flamingo’, Aleksandr Demyanov was sent back into the USSR.

The game begins

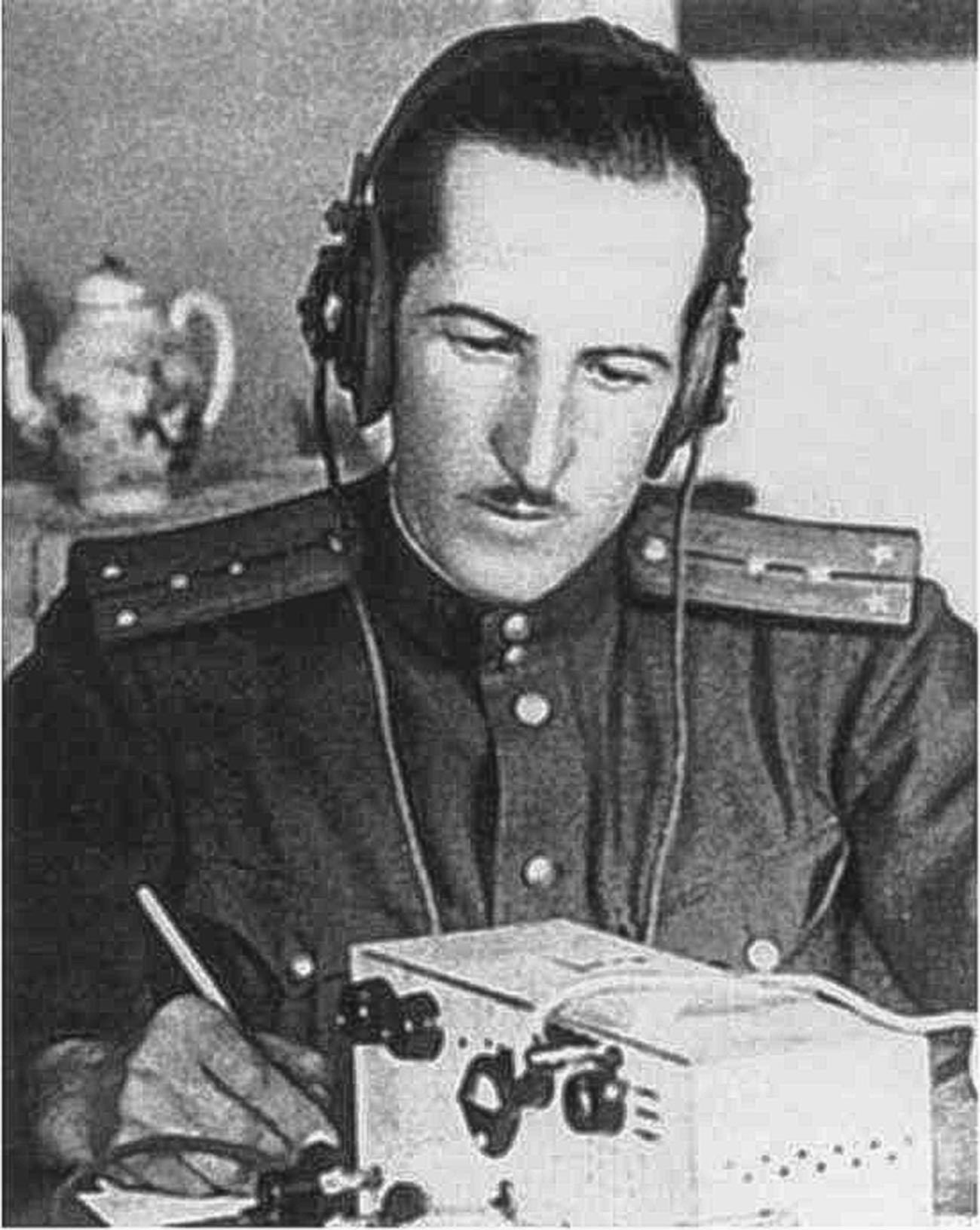

Heine had by then been considered dead by Moscow. When the man suddenly resurfaced, operation Monastyr was terminated, and a “radio game” with Germans began.

The first order of business was to earn German trust by putting the anti-bolshevik underground through its paces. Flamingo reported of Prestol’s plans to mount a diversion behind Soviet lines. Pretty soon, Soviet newspapers started to publish news of bombings of industrial sites in the Urals and Siberia, carried out by “fascist affiliates”. None of this was true, of course, but faith in Flamingo’s loyalty really took off from there.

Irreplaceable agent

On June 22, 1942, the anniversary of operation Barbarossa, the Luftwaffe was busy preparing a real gift for the Fuhrer - an all-out attack on Moscow. Demyanov was tasked with doing a survey of the capital’s anti-air defenses. Soon thereafter, the Nazis received the following telegram: “The city contains a large number of new fighter aircraft and zenit artillery. New technologies will be applied in the coming days, affording a wider capacity for intercepting enemy aircraft at higher altitudes.” The Germans promptly cancelled the attack.

Gradually, Flamingo became one of the most useful agents of the Abwehr on the Eastern front. He ended up “serving” in the People’s Commissariat for Communication, and later even managed to become an officer at the General Headquarters.

The Third Reich was being fed a stream of disinformation, diluted with some truth from the General HQ to make it all look genuine. Flamingo managed to find out about moles and spies inside the USSR. The Soviets would then catch them, while including others in their “radio game” with their former masters.

Using this approach, more than 20 enemy agents were deactivated, as well as millions of rubles confiscated.

Major operations

Operation Monastyr played a key role in deciding the outcome of major battles along the Eastern front. On November 4, 1942, Heine told Germany that the Red Army would retaliate in the North Caucasus and under Rzhev - instead of Stalingrad. As a result, the Germans sent their troops to those areas.

Operation Mars, or the attack on Rzhev, was a failure. But it was Stalingrad - where the 6th Army became surrounded by Soviet forces - that caught the enemy by complete surprise.

“[Marshal] Zhukov, who had been unaware of the radio game, paid a heavy price - he ended up losing thousands and thousands of our soldiers under his command at Rzhev,” Pavel Sudoplatov, Demyanov’s direct superior, remembered. “In his memoirs, he confesses that the outcome of the attack had been unsatisfactory. However, he would forever remain none the wiser to the fact that the Germans were warned of our attack near Rzhev, thus moving such a great number of their troops accordingly.”

Heine’s disinformation campaign also played a major role in forcing the Germans to postpone the attack under Kursk, which gave the Red Army a much needed head start to prepare.

By 1944, the Soviet side was on a decisive march forward, and operation Monastyr was wrapped up, having lost all meaning. Legend has it that Flamingo was demoted to an insignificant post without access to sensitive information, and left the radio game for good.

Interestingly, Aleksandr Demyanov was awarded not only the Soviet Order of the Red Star, but even received, in absentia, the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross from the Nazis. The Germans would continue to believe, until the end of the war, that Flamingo’s heart and soul belonged to the Reich.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox