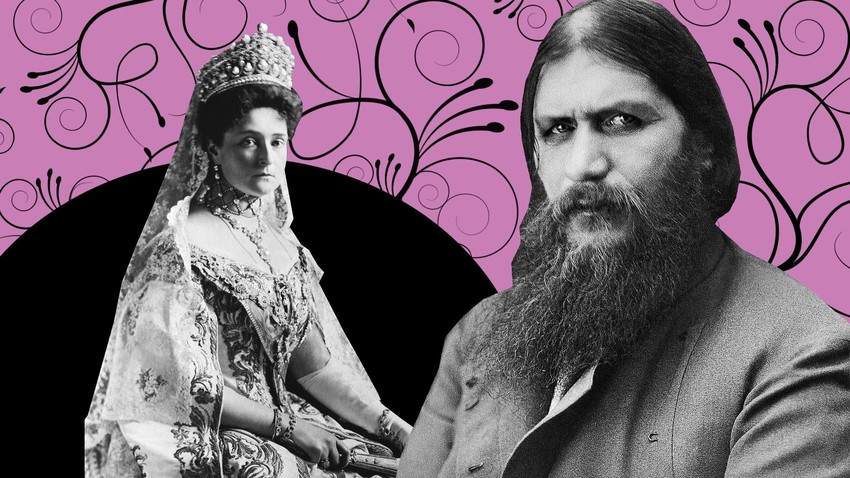

No, Rasputin wasn't the Russian queen's lover

Grigoriy Rasputin (1869-1916) was a controversial figure at the Russian Imperial court of the early 20th century. He surely wasn’t a saint or even a virtuous person – but what made him a friend of the tsar’s family was his ability to stop bleeding in Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich, the tsar’s hemophiliac son.

Could Rasputin really heal Tsarevich Alexei?

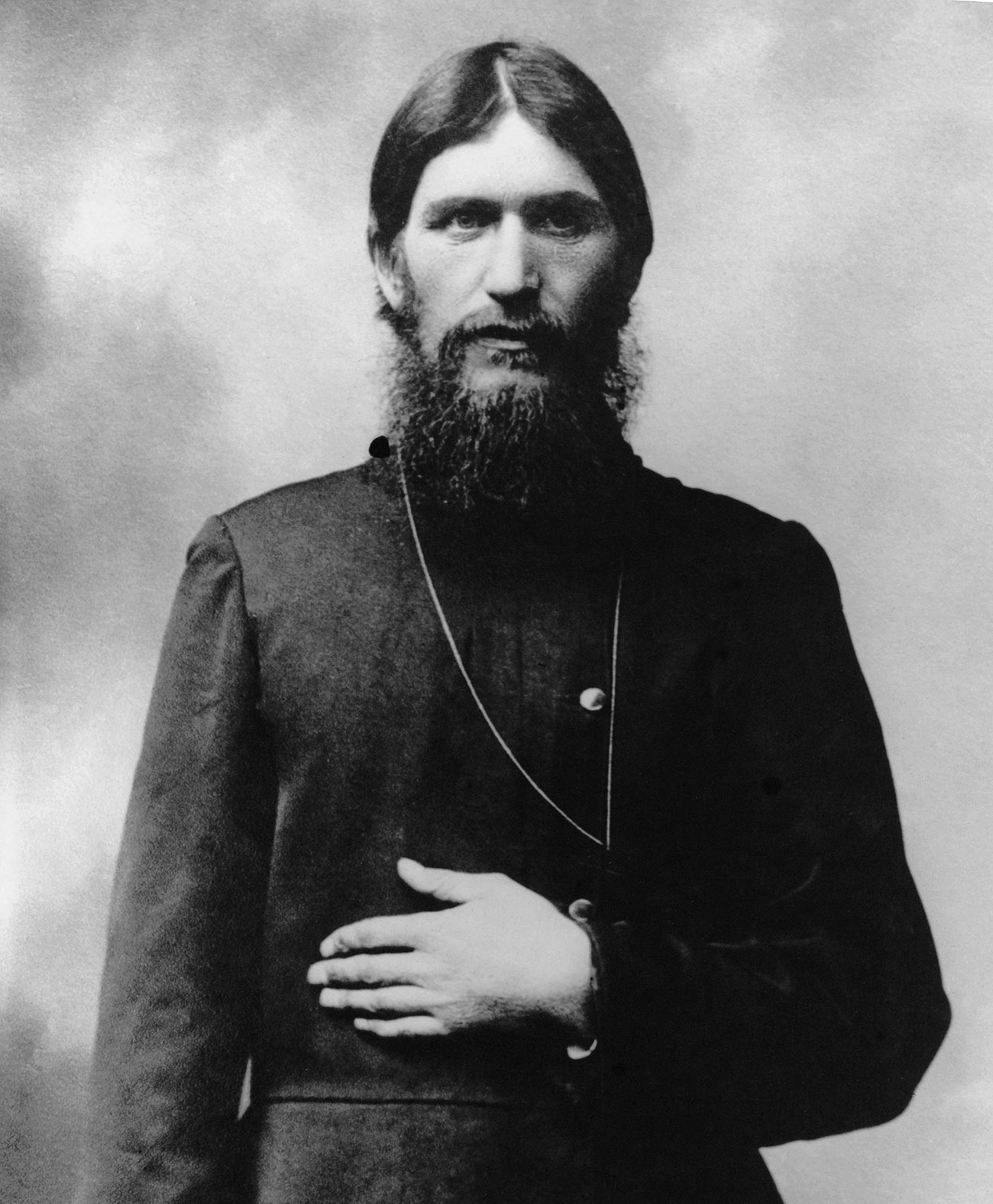

Grigoriy Rasputin in 1904. In this photo, he is 35.

Karl BullaWhen Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna first encountered Rasputin, she already knew that the medical science of her time didn't have a cure for haemophilia, the illness of her son Alexei. So she was ready to try anything that could help the boy, who bled unstoppably from the tiniest cut.

Rasputin’s healing abilities have been confirmed by so many contemporaries it’s hard to doubt them. His healing powers have been described even by people unlikely to believe in miracles, for example, Pavel Kurlov, deputy minister of the interior in 1909-1911, who wrote that “Rasputin had undoubtedly the ability to calm [people] down, and beneficially influenced the underage heir during his illness.” Mikhail Rodzianko, Chairman of the State Duma, also wrote that “Rasputin possessed a great deal of hypnotism. He must have been of great interest to science.”

Alexei Nikolaevich (1904 - 1918), Tsarevich and heir apparent to the throne of the Russian Empire.

Global Look PressIn summer 1907, Rasputin first helped the three year-old heir to overcome internal bleeding. The monk just stood at the feet of the heir’s bed and prayed. After that, Rasputin regularly stopped Alexei’s bleeding. In 1912 in Crimea, he was summoned to stop sudden kidney bleeding.

What was the nature of the relationship between Rasputin and Empress Alexandra?

Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna (1872-1918)

United States Library of CongressEmpress Alexandra Fyodorvna suffered from migraines and heart spasms. Many doctors recommended her to “tend to her nervous system.” Rasputin had the ability to calm her down, just like he did with the heir. But Alexandra Fyodorovna and Emperor Nicholas had a long-lasting, strong relationship. They wrote regularly to each other, they both were very concerned about the fate of their ill son, and they spent little time apart. However, Alexandra was indeed fond of Rasputin, and in a very affectionate way.

“How weary I am without you. I only rest my soul when you, the teacher, are sitting next to me, and I kiss your hands and lean my head on your blissful shoulders. Oh, how easy it is for me then. Then I wish all the same: to sleep, to sleep forever on your shoulders, in your arms.”

These are the genuine words Empress Alexandra wrote to Grigoriy Rasputin, and they became the ground for the legend about their alleged sexual relationship.

Who created the legend?

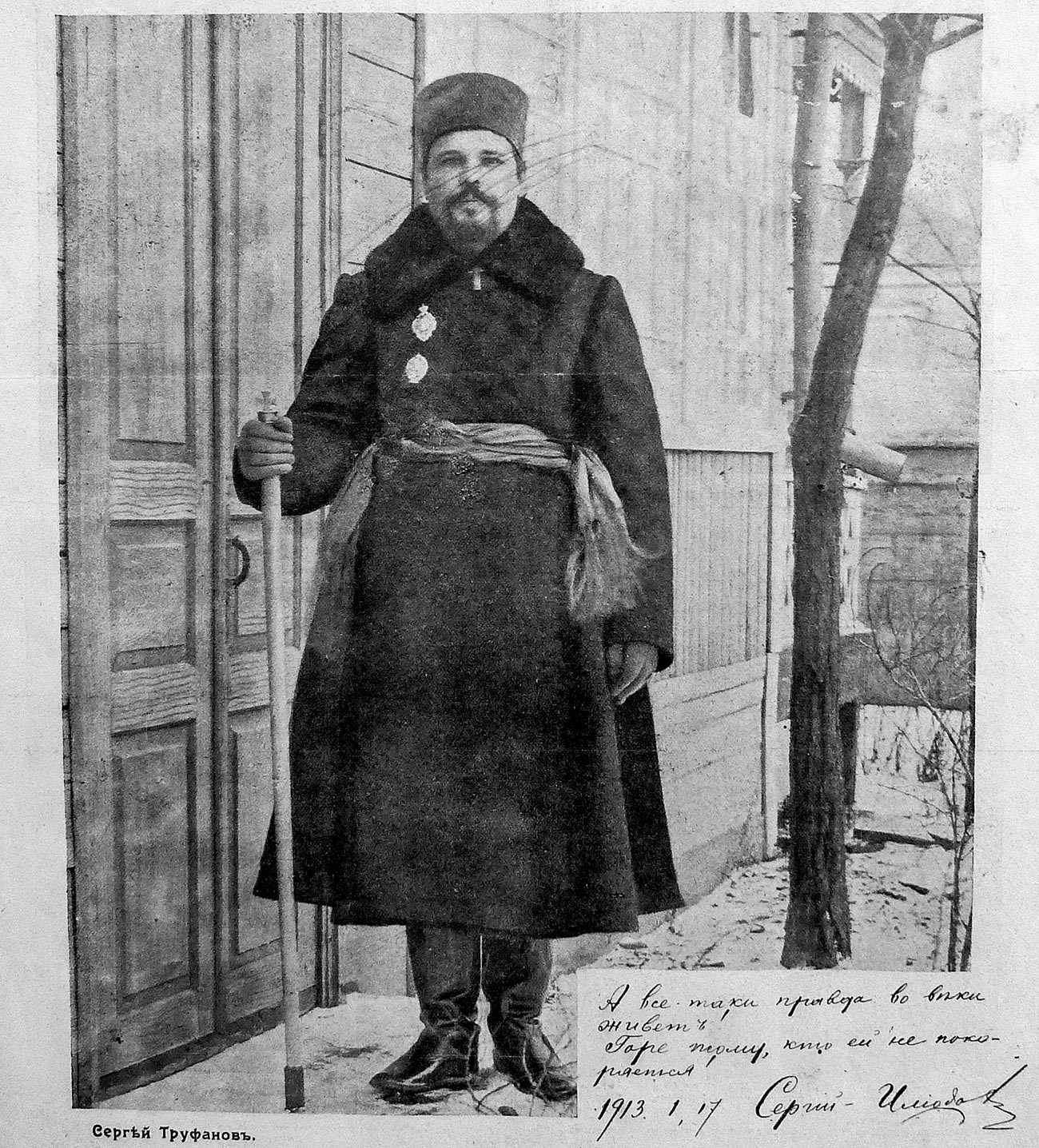

Sergei Trufanov, aka Hieromonk Iliodor (1880-1952)

Public domainWe may say that Rasputin himself contributed to his notoriety – because he shared the letters the Empress sent him, with a friend.

The letters were from 1909-1910, and Rasputin showed them or gave them to a shady person named Sergey Trufanov, or Hieromonk (Orthodox monk) Iliodor. Iliodor met Rasputin in 1904 and became his protegee. Iliodor preached massively and proclaimed himself a miraculous healer. He used Rasputin’s connections to defend himself against the Russian Holy Synod that was against his manic preaching and mass gatherings he organized.

In 1912, Iliodor and Rasputin had a row and even a fight, and Rasputin stopped protecting the hieromonk who was immediately put into a cloister (Florischeva pustyn’) for spiritual penance. In his containment, Iliodor wrote “The Holy Imp,” a book denigrating Grigoriy Rasputin – and published the Empress’s letter which immediately became a viral news hit. Now, everybody thought Rasputin had slept with the Empress, because she wrote she wanted to “kiss his hands.”

Was the letter genuine?

Although many pro-Romanov historians argue that Iliodor made up the letter, many sources prove that it was genuine. In 1914, after a peasant woman Khioniya Guseva tried to assassinate Rasputin, he himself testified that in 1910, Iliodor stole some letters from the Empress to Rasputin from Rasputin’s home in Siberia where Iliodor was a guest.

Vladimir Kokovtsov, Prime Minister in 1911-1914, wrote that Alexander Makarov, minister of the interior, showed the letters to Emperor Nicholas II (the police managed to get the originals back), and the Emperor was enraged upon recognizing his wife’s handwriting. Soon after that, Makarov was fired. Although the letters were returned, all of Russia gossiped about Rasputin and the Empress.

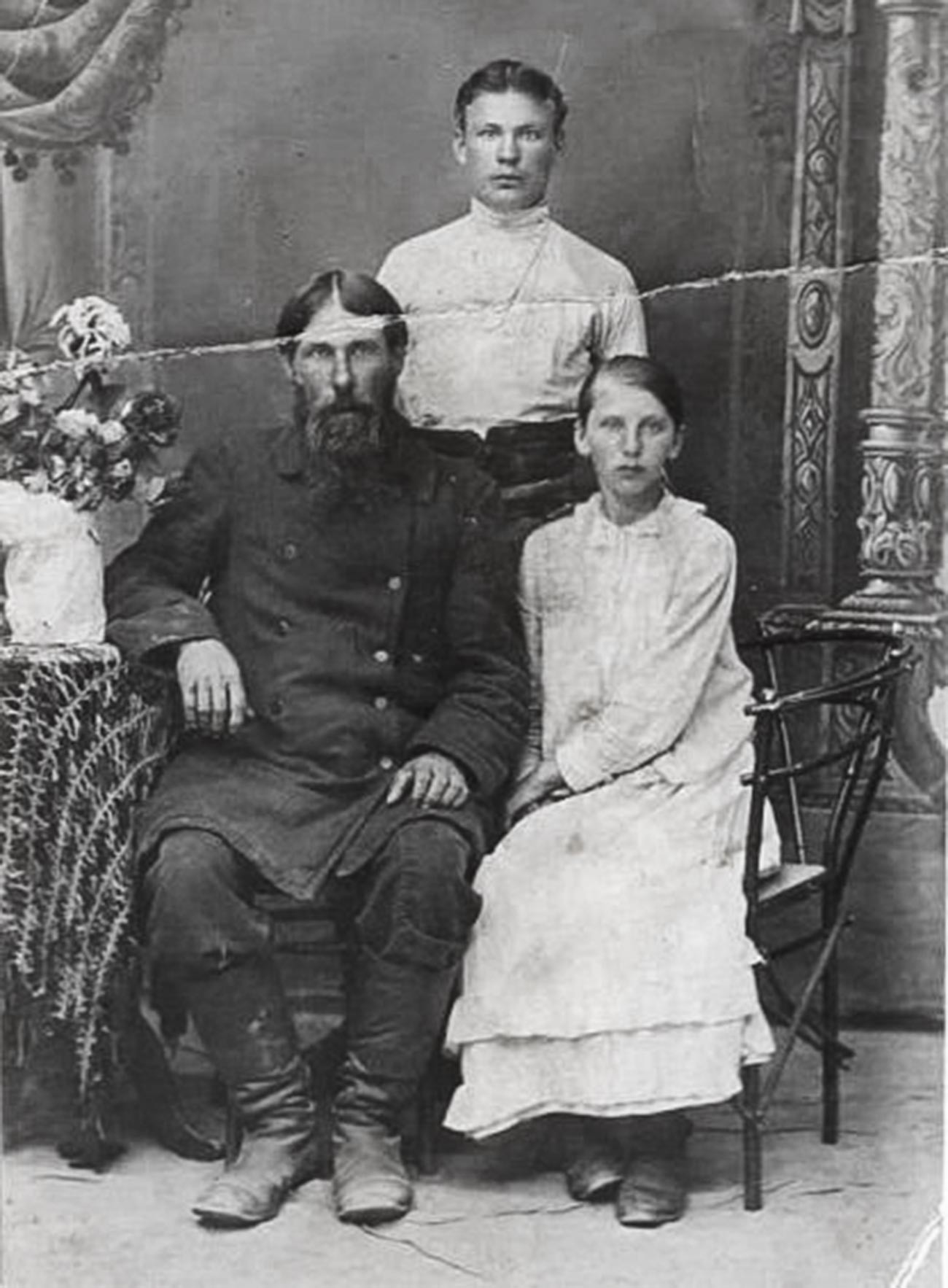

Obviously, Russian people of the early 20th century didn’t have TV. They hardly knew what Rasputin looked like. For example, this photo was sold from public bookstands at town fairs as “Rasputin and children.” We can clearly see that this isn’t Rasputin, but Russians of his time couldn’t.

A photo of the unknown persons sold as "Rasputin with children"

Public domainThis photo depicts Rasputin and his circle of followers, including a Russian lady-in-waiting, Alexandra Fyodorovna’s friend, Anna Vyrubova, and Rasputin’s disciple Maria Golovina (seated left of Rasputin). Russian people bought prints of this photo, thinking Golovina was the Empress. So ignorance only contributed to the myth.

Rasputin and his admirers, 1914. His telephone can be seen on the right. This image has been widely reproduced in the press and various books since 1917.

Karl BullaCould Rasputin and Empress Alexandra really have had a sexual relationship?

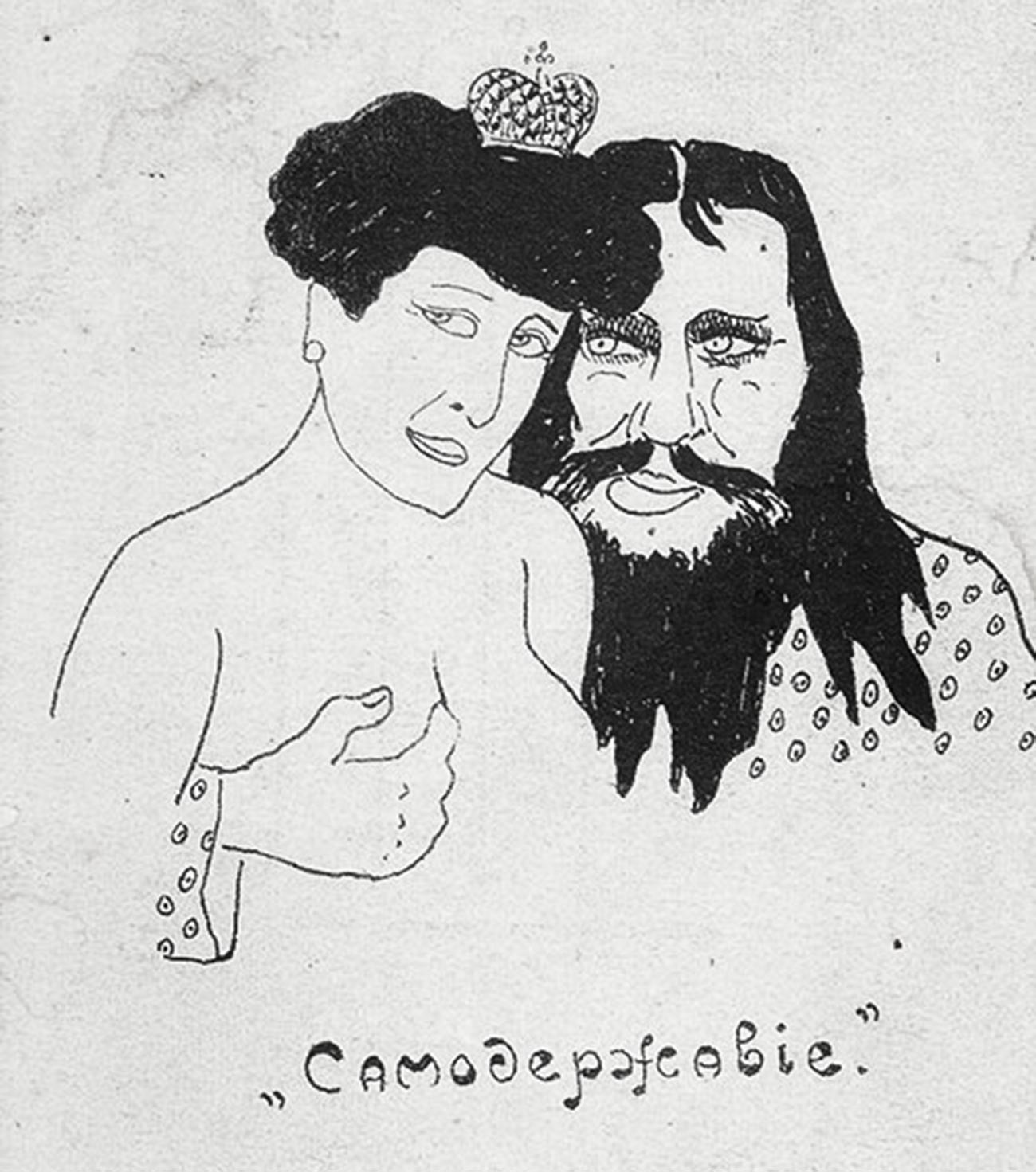

"Autocracy". A cartoon depicting Rasputin and the Empress.

Public domainFor Alexandra Fyodorovna, Grigoriy Rasputin was definitely the healer monk, the “holy elder”, although Rasputin was barely three years her senior. She definitely trusted him and relied on his help, but for the Russian Empress, he was just a muzhik, a peasant man, even if one who possessed healing powers.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox