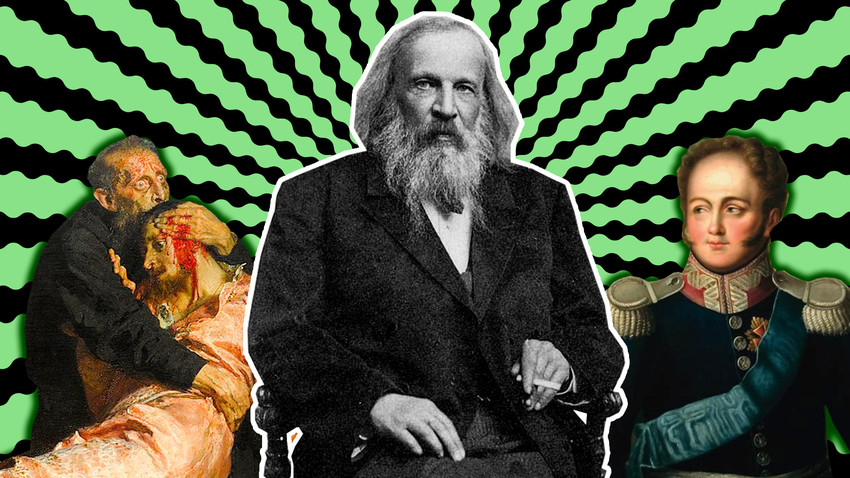

3 myths in Russian history that won't die

1. Emperor Alexander didn’t really die but became a vagabond

Alexander I of Russia (1777 – 1825)

Public domainIn the years before his death, Alexander I of Russia seldom talked about his wish to withdraw from public life. In 1819, he said to his brother Nicholas: “I’m not who I used to be and I think it is my duty to withdraw.” In 1824, he said he wouldn’t mind “throwing off the burden of the crown.”

In the autumn of 1825, Alexander traveled to Taganrog with his wife and abruptly died there because of a fever. An autopsy was performed, and an act was signed by 9 doctors. After embalming, the emperor’s body was transported to St. Petersburg, but only the members of the Emperor’s family saw the emperor in the open coffin; during the subsequent 7 days that the body was in the Kazan Cathedral for public farewells, the coffin was closed.

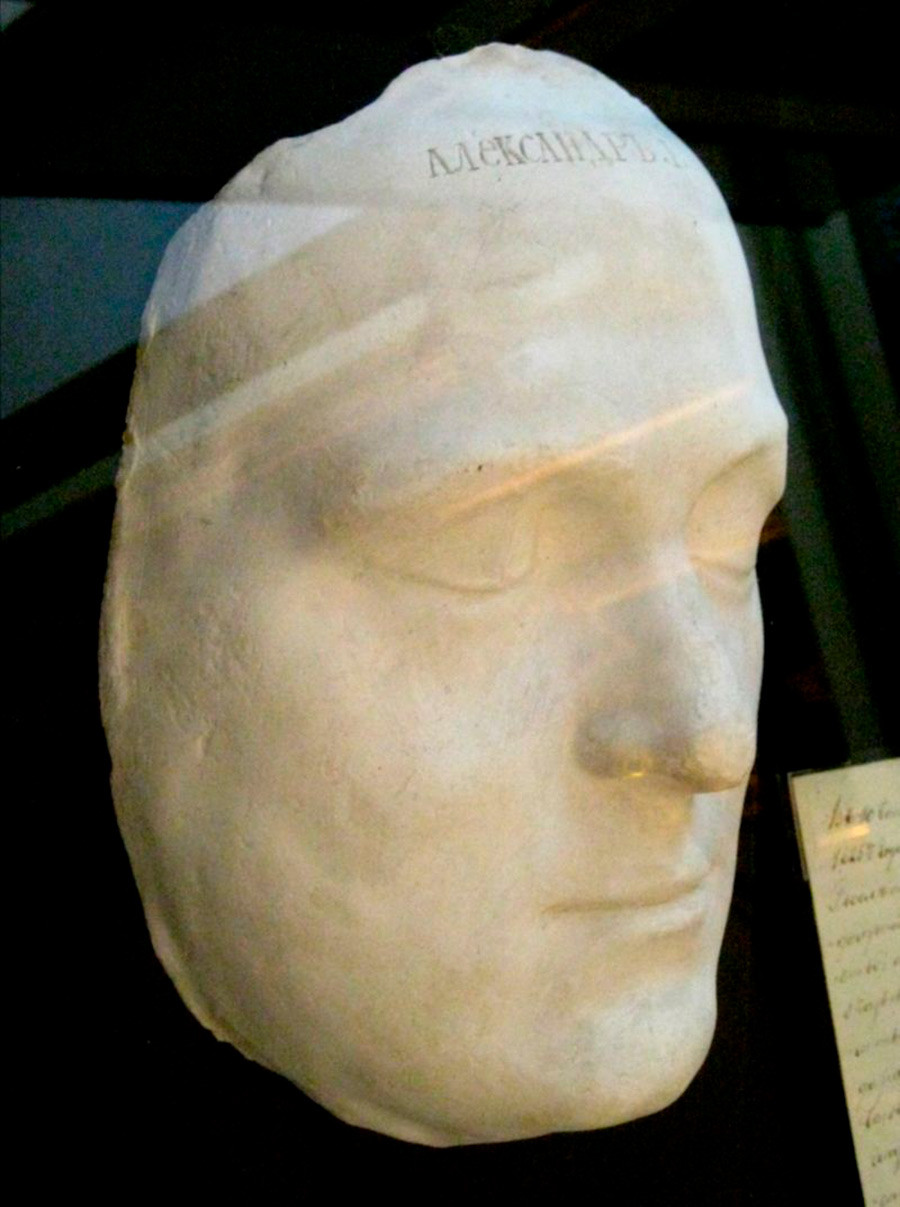

Alexander I's death mask

shakko (CC BY-SA 3.0)In 1836, in Perm’ Region, an old man was been apprehended for vagrancy. He called himself Fyodor Kuzmich and was tall with grey hair. He was very physically fit, seemed educated and gentle, but refused to say anything about his past. For vagrancy, Fyodor was sent to Siberia, where he lived and then died in 1864. During his life, he often told stories of St. Petersburg and of famous people, including military commanders Kutuzov and Suvorov – apparently, the old man took part in the War of 1812.

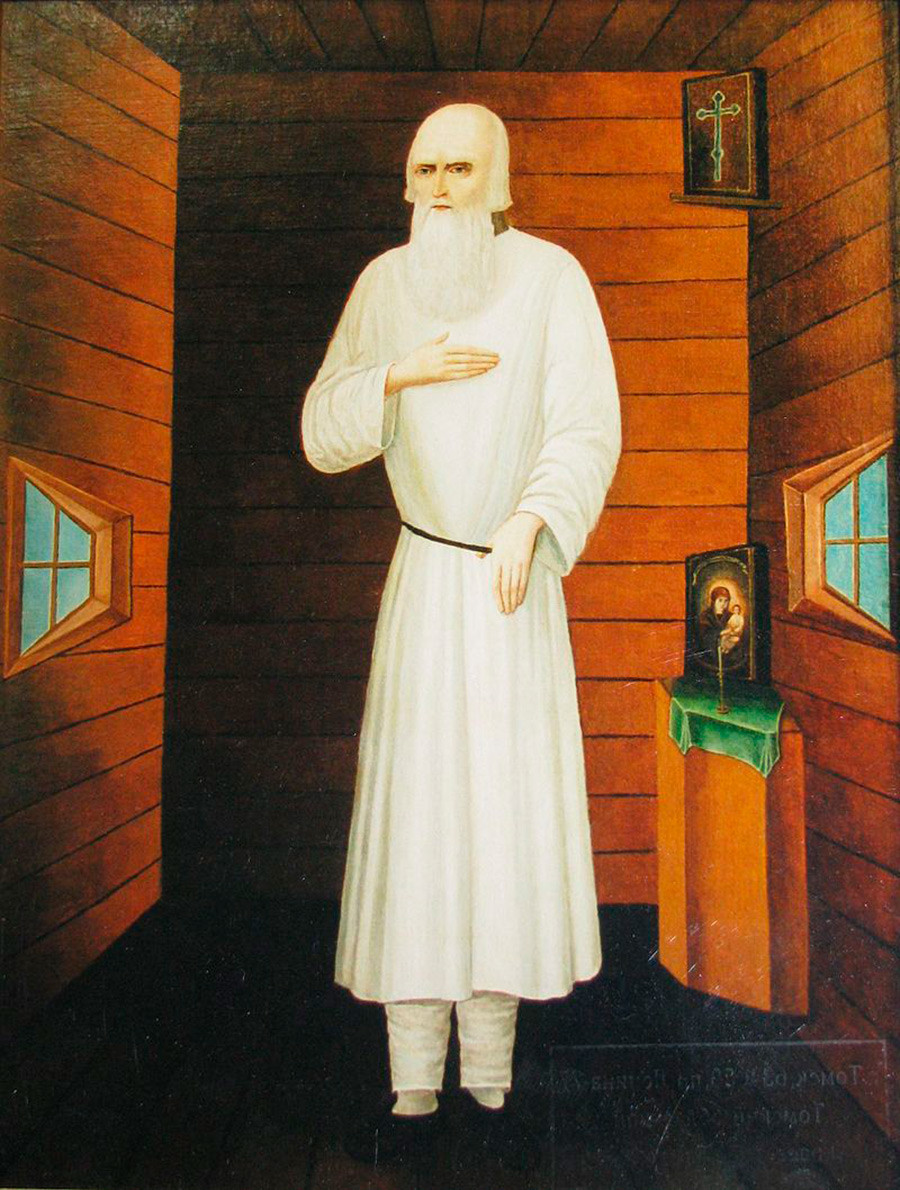

But who was the first to suggest that Fyodor was Alexander in disguise? Allegedly, Semyon Khromov, a merchant who invited Fyodor to live in his house in Tomsk and was completely sure that the old man was the Emperor – which accidentally made Khromov a celebrity of sorts. So it’s no wonder Khromov even tried to write to Alexander II – but in 1882, when he was apprehended by Tomsk authorities, Khromov said he really knew nothing about the old man’s past. Fyodor himself, while alive, didn’t deny nor confirm the legend.

The portrait of Feodor Kuzmich (died 1864)

Tomsk Region Local History MuseumBefore his death, Fyodor gave Khromov an encrypted message that was to reveal his identity, but the message still hasn’t been deciphered up to the present day. Russian historians agree that Fyodor Kuzmich existed, but he wasn’t Alexander I – Fyodor probably was some high-ranked nobleman in the military service, but definitely not the Emperor.

2. Dmitri Mendeleev dreamed up the periodic table

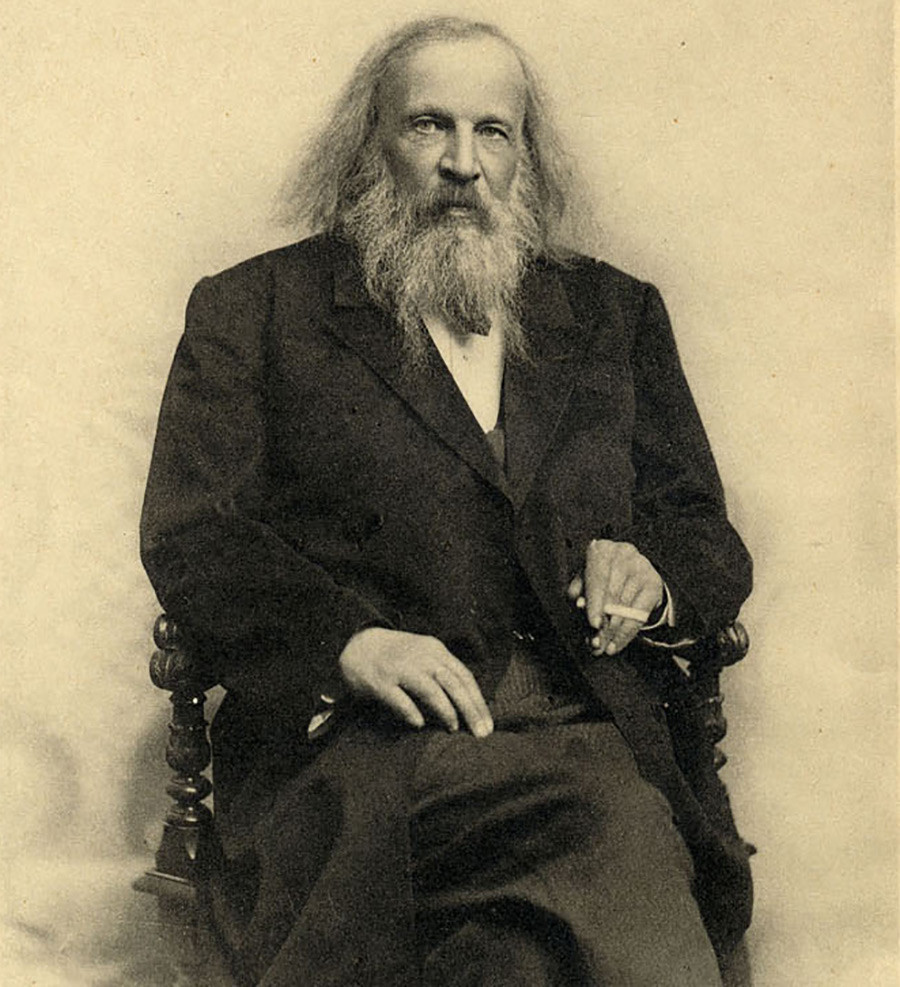

Dmitri Mendeleev (1834 – 1907)

Public domainThe legend goes as follows: in 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev strived to discover the periodic trends in the properties of chemical elements. Exhausted, he once fell asleep at his desk and dreamed up the table he couldn’t compose while awake. Springing up from his slumber, Mendeleev took a pen and a paper and quickly drafted the periodic table of elements.

Alexander Inostrantsev (1843 – 1919), Mendeleev's friend

Petersburg Academy of SciencesMendeleev himself never told anyone this story. But his friend, geologist Alexander Inostrantsev, often retold Mendeleev’s alleged story about discovering the table while asleep, despite Mendeleev himself denying this. Speaking to a journalist for the Peterburgskiy Listok (The St. Petersburg Paper) newspaper, he said: “No! Not a dime for a line, as you journalists do! I could have well spent 25 years inventing it [the periodic system], and you say I was just sitting there, and all out of the blue – one dime a line, one dime a line, and it’s cooked!”

Also, Mendeleev wasn’t the first to create a periodic table – in 1864, German chemist Julius Lothar Meyer created one, consisting of just 28 elements.

3. Ivan the Terrible killed his son with a staff

'Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan' (1883–1885) by Ilya Repin (1844 – 1930)

Ilya Repin/Tretyakov GalleryThis myth was, in large part, created by Ilya Repin’s painting ‘Ivan the Terrible and His Son’. However, the chronicles don’t contain any information on this, they just say Ivan’s son Ivan died because of “a disease”.

In 1963, in Moscow Kremlin’s Arkhangelsky Cathedral, the place of interment of the Russian tsars, corpses of Ivan the Terrible and his sons Ivan and Fyodor were temporarily exhumed. All of them contained arsenic, usual for those times when tsars took homeopathic amounts of arsenic to develop tolerance to it – as it was the most common poison. However, the bones of Ivan and his son Ivan also contained high levels of mercury. Later in the 1990s, comparably high levels of mercury were then found in the bones of Anastasia, Ivan the Terrible’s first wife, and his mother Yelena Glinskaya. The research made it clear that Ivan the Terrible’s family has most likely fell victim to poisoning.

It is widely reported that Ivan was devastated after his elder son’s death. Ivan spent 4 full days next to his son’s bed, while Ivan Jr. was dying. This fact doesn’t fit in the image of a madman who slaughtered his son. Moreover, Ivan the Terrible was preparing Ivan Jr. for tsardom, making him a military commander and summoning him to discuss state affairs. So it was unlikely that Ivan could kill his heir, given the disastrous consequences it would bring – a dynastic crisis. It was clear Ivan’s death was a catastrophe, but who needed it to look like the Tsar killed his son?

'Papal legates at Ivan the Terrible's' (1884) by Mikhail Nesterov (1862 – 1942)

M. NesterovThe first mention of Ivan murdering his son is found in the papers of Antonio Possevino, a papal legate and the first Jesuit to visit Moscow, who tried to convince Ivan the Terrible to negotiate with the Pope about Russia becoming a Catholic country. When Possevino’s mission failed, the enraged legate smeared the Russian tsar with the accusation of filicide. This defamation was readily spread by other foreign and Russian foes of Ivan the Terrible. And finally, at the end of the 19th century, even made it onto Repin’s famous painting.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox