Debunking 5 myths about how St. Petersburg was built

1. St. Petersburg was founded on a vacant plot in the swamps

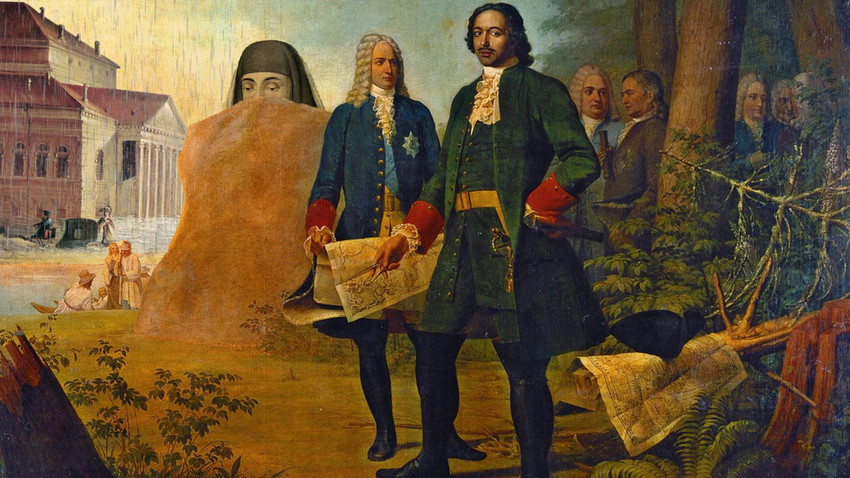

Valentin Serov, Peter I on the Neva Embankment, 1907

Global Look PressFirst, the place was a bustling spot. Already in 1300, a Swedish fortress named Landskrona was erected here, and later, in 1611, the fortress of Nyenskans took its place, with the Swedish town of Nyen around it.

In the 17th century, Nyen became a big trading center, due to its favorable location near the sea and at the confluence of several rivers. This is why, when in 1703, Peter the Great took Nyen during the Great Northern war of Russia and Sweden, he decided to build a new city here – to further establish Russia’s military presence on Swedish territory and finally secure Russia’s access to the Baltic sea. And there’s a peculiar fact: when St. Petersburg became Russian capital in 1712, it was still formally on the Swedish territory (the St. Petersburg region became fully Russian only after the Northern War ended in 1721).

Model of the Nyenskans fortress

Evgeny Gerashchenko (CC BY-SA 2.5)So where did the “swamp” rumor come from? Indeed, in 1705, two years after the city’s foundation, one fifth of its territory was marshland. A giant swamp was, indeed, on the place of Paul I’s Mikhailovsky Castle. And an impassable slough occupied what is now considered the city’s pinnacle of nightlife, Dumskaya street.

But the city was constructed with the help of European urban engineers. They ordered soil to be brought to St. Petersburg to solidify the ground under heavy buildings. As soil scientist Elena Sukhacheva says, beds of springs and tiny rivers were filled with sand and rubble, and swamps were drained. This all was executed gradually until the 1780s when the Neva River’s shores were finally dressed in granite.

2. An eagle soared in the skies when Peter the Great founded St. Petersburg

Boats on the Neva River in front of the Peter and Paul Fortress - lithograph - Early 19th century

Getty ImagesThe Peter and Paul Fortress was founded on May 16th, 1703. There’s a persistent rumor that Peter himself laid the first stone in the foundation of the fortress while an eagle was flying over his head.

However, this is a complete myth. According to the tracklog of Peter the Great, on this day, Peter was stationed much further North, in Schlötburg, at the place of the former Nyenskans fortress (all his decrees and letters from May-June 1703 are signed in this place). Finally, no eagles ever inhabited St. Petersburg region.

3. The city was built on bones

"Peter I at the Construction of Saint Petersburg", by Georgy Pesis.

Leonid Sievert/SputnikLegend has it that Peter the Great ordered thousands of peasants from Russian regions to build St. Petersburg. They were ill-fed, suffered from moisture and frost and died in swarms, buried right there in the swamps. This horrible tale ends with “this is why St. Petersburg is built on bones”.

It’s true that construction works were performed by peasants, although they weren’t just ordered to come to Petersburg, but rather commissioned. As of 1704, 40 thousand workers were summoned to St. Petersburg, mostly state serfs or landlords’ serfs.

The peasants worked in shifts: after three months, they were allowed to go home. However, many of them stayed for the next three months, as the work paid 1 ruble per month, a standard worker’s pay at the time.

After 1717, there were no more peasant workers, but an annual tax was instead introduced. For the construction, the government commissioned workers and paid them with the tax money.

As for the death rate among workers, it was usual for the population at the time. In the 1950s, a Soviet historian conducted excavations on the major building sites of the 18th century and didn’t find any evidence of mass perishing, just cesspools filled with animal bones. This only proved that workers were fed good rations that included lots of meat.

4. Vasilyevsky island should have had canals, but Menshikov stole the money

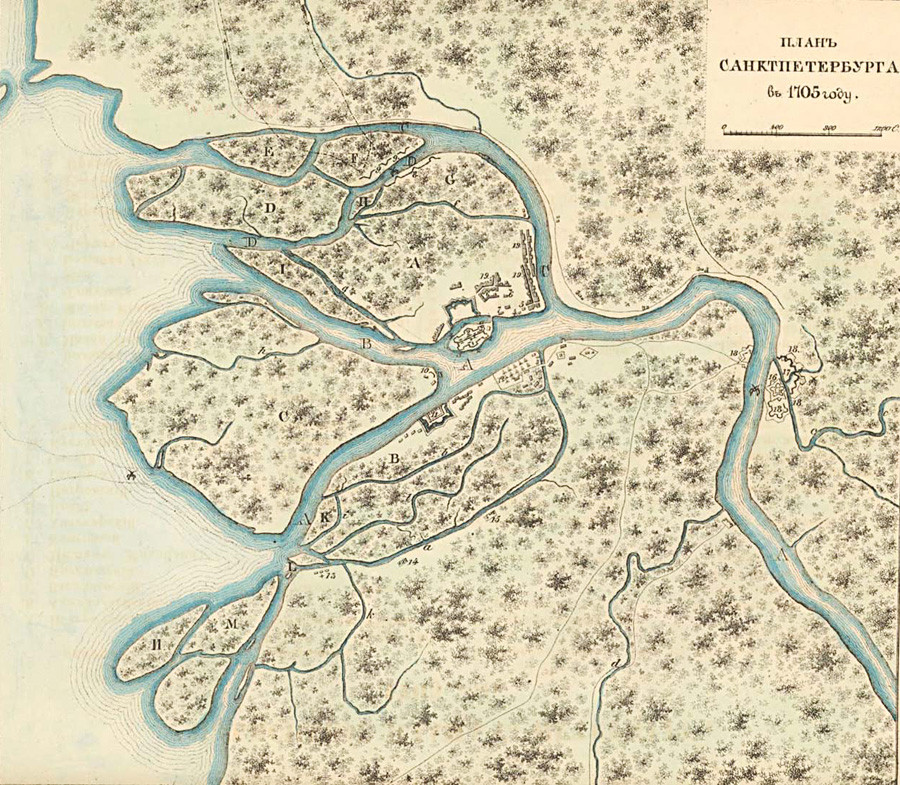

Plan of the city, 1705

Public domainJacob von Staehlin (1709-1785), member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, who lived under several Russian monarchs, states in his book ‘Original anecdotes of Peter the Great’ that Peter ordered the Vasilyevsky island in St. Petersburg to become a “little Amsterdam” with canals instead of streets, and commissioned the task to his henchman, Prince Alexander Menshikov. But the prince, who was a notorious cheat, stole most of the money, so the canals turned out too narrow for boats to sail and were eventually backfilled.

Portrait of Aleksander Danilovich Menshikov

Public domainIn reality, even in 1723, there were no canals on Vasilyevsky island. Only in 1727-1730 (after Peter’s death), did four canals appear, which were then backfilled at the order of Catherine the Great in 1767.

5. 'Petersburg will be empty!'

Tsarina Eudoxia (Yevdokiya Fyodorovna Lopukhina) (1669-1731) - first wife of Peter I the Great of Russia.

Viktor Kornushin/Global Look PressPeter the Great didn’t love his first wife, Evdokia Lopukhina, who was a woman of old formation and didn’t share Peter’s passion for everything European. Evdokia was said to have taken part in a conspiracy plot against Peter, so he sent her to a convent, tonsuring her forcibly. Before leaving for the convent, Evdokia shouted about St. Petersburg: “This place will be empty!”

READ MORE: Peter the Great and his women

The Flood of 1824 in the square at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre by Fyodor Alekseyev

Russian MuseumHowever, Evdokia could hardly have known anything about St. Petersburg when she was sent to the convent in 1698, 5 years before the town of Nyen had been conquered and the ‘place’ she was talking about was only defined as the construction ground for the future city. So Evdokia couldn’t have predicted that this swampy place will be subject to many floods (as her ‘prediction’ was usually interpreted).

READ MORE: The first Romanov political exile: How Peter the Great's son fled Russia

However, Prince Alexei, the ill-fated son of Peter and Evdokia, repeated the rumor in 1718 when he was interrogated. We believe he just repeated a rumor. But later in the 19th century, Russian historian Sergey Solovyev told this tale once again, and from then on it became a pseudo-historical fact.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox