The HORRIFIC famines of the Soviet Union - and why they happened (PHOTOS)

The first instance of mass hunger struck the Russian Empire right after the end of the Civil War, which disrupted the country’s internal economic ties, becoming the leading cause of food shortages. Another factor was the harsh drought of 1921, which destroyed a fifth of the country’s crops.

Faced with an agricultural deficit, the government ramped up its program of confiscating grain from the population, exacerbating the situation even further. Soon, the hunger spread across most of the country and its 90 million inhabitants - from the Kazakh steppes to the Urals and across to Southern Ukraine and Crimea.

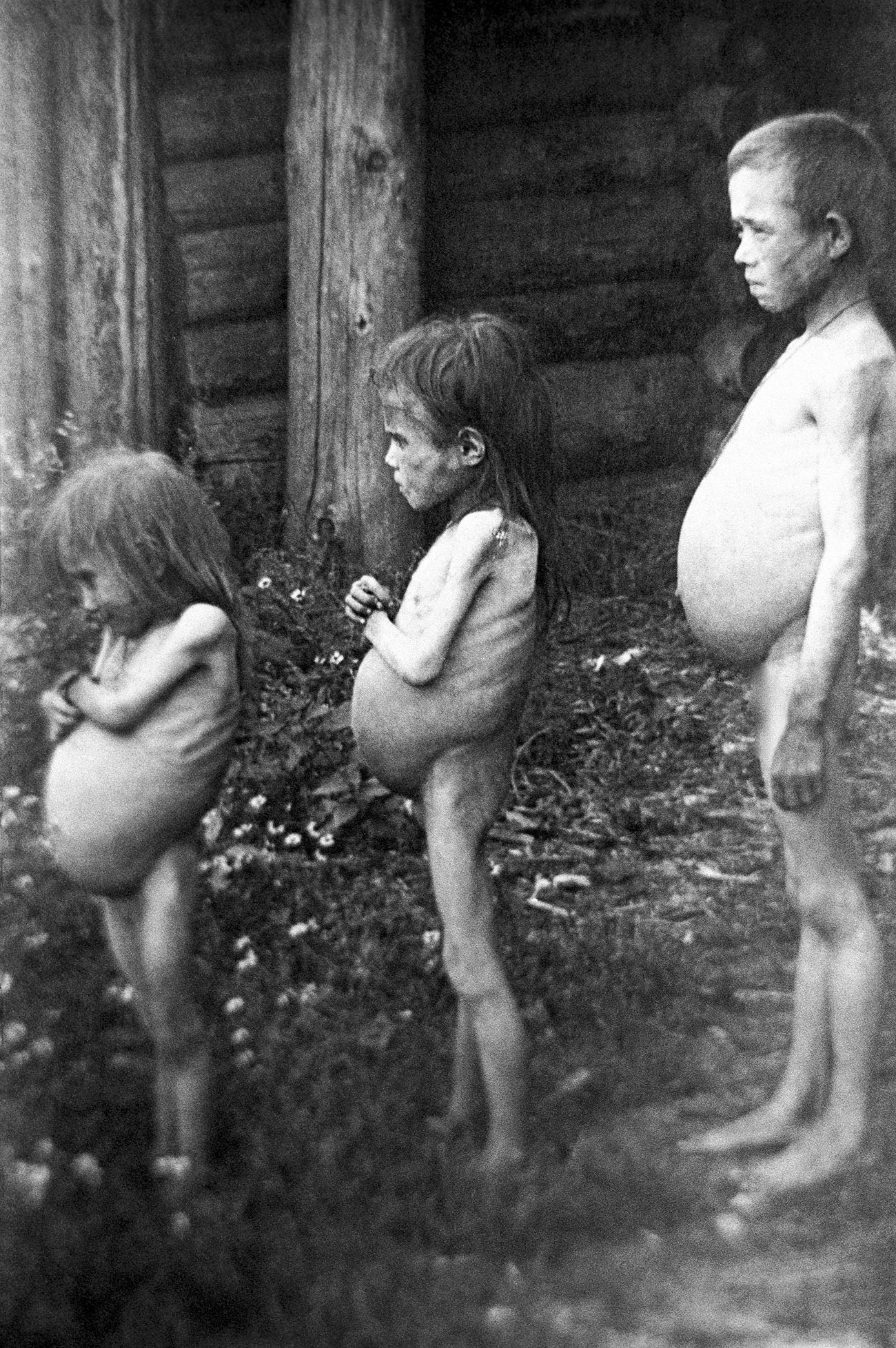

Upon visiting villages in the Saratov and Samara Regions in 1921, sociologist Pitirim Sorokin made the following observations: “Shacks that stood abandoned, roofs missing, empty window sockets, and no doors. The once-present straw roofs have long been taken down and consumed as food. The village, of course, was void of animals - no cows, horses, no sheep, goats, dogs or cats - not even crows. All were eaten. A dead silence hung over the snow-covered streets.”

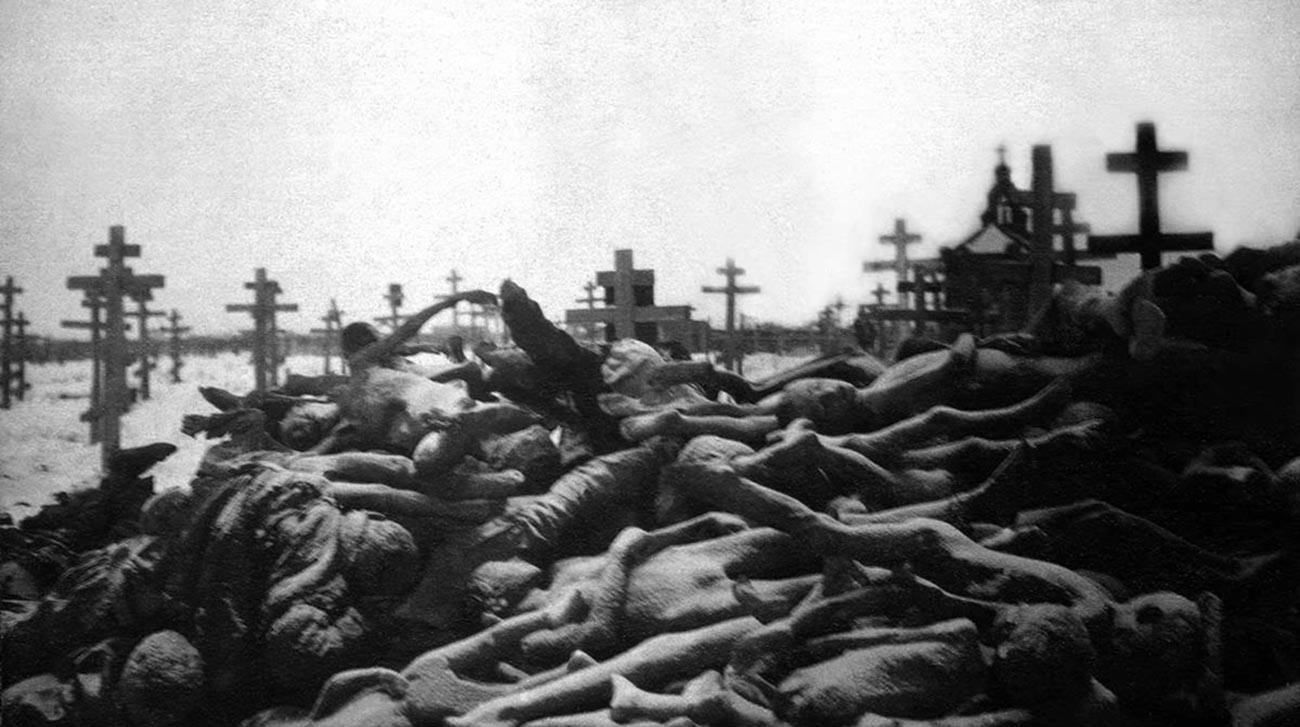

An all-out exodus had begun. People would sell and abandon all of their life’s possessions, running wherever their legs would take them, with no concrete plan. Cannibalism had become rampant in select locales: people would be hunted down on the streets in broad daylight and murdered for food, with families often consuming their small children, sparing them the pain of a hungry, torturous death - and to fill up on much needed sustenance.

Cannibals with their victims.

Public domainThe Soviet government had for long hidden the horrible truth, but, finally, in the summer of 1921, it was decided to turn to the international community with an appeal for aid. Numerous charity organizations answered the call, as well as famed Arctic explorer and public figure, Fridtjof Nansen, who personally arrived in Russia with the collected humanitarian aid. It is this kind of support that - combined with a good harvest in 1922 - enabled the country to stop a mounting catastrophe in its tracks, having already claimed five million lives.

However, 10 years later, another famine struck. A painful process of collectivizing private peasant property into ‘kolkhozes’ (collective ownerships) and the ‘raskulachivaniye’ (dispossession) of owner-peasants led to millions fleeing the resulting hunger. Choosing to double down on its ignorance of the impending crisis in Soviet villages, the government only increased its demands for bread production. Any protests put up by the peasantry were considered sabotage, and ferociously struck down.

Local governments were caught in the middle, trying to fulfill quotas on the one hand, and attempting to avoid punitive measures on the other, in the case of failing. This led to Moscow receiving a lot of false or distorted information, concealing the horrific actual scale of the misery.

As a result, the 1932-33 famine had gripped most of Ukraine, the Caucasus, Kazakhstan, Belarus, western Siberia and some other regions in European Russia. The horrors of the 1920s had once again returned. As the inhabitants of the Kuban region remembered, “Nobody had paid any attention to the dead, there was no strength left - just total indifference.” Cannibalism was on again - children had begun to disappear once more. In Sverdlovsk (today Ekaterinburg), a worker father and his son failed to find their names on the list for monthly food rations. They committed suicide on the same day, jumping in front of a tram. As was later discovered, someone had simply forgotten to include their names.

“My father left in search of bread and never returned. Soon, the brother left - and also never came back. We were left just the two of us with my mother”, Aleksey Stepanenko, a Ukrainian from Russia’s Khabarovsk Region remembered. “My mother - in apparent anticipation of death, told me then: ‘When I start to die, I will strangle you, too, so that you don’t die a hungry death.’ That evening, my poor mother gave her soul to God. Seven years old at the time, I was put in village foster care.”

More than seven million people died as a result of the 1932-33 famine. The fact that more than half of the casualties were Ukrainian has given modern Ukrainian researchers a firm reason to treat the period as a deliberate program of genocide of the Ukrainian people at the hands of the Soviet rule. The name given to it was “holodomor” (a composite noun, meaning literally - “to starve someone to death”). Russia, meanwhile, has its own perspective - that the harmful policies of the communists simply hit most of the territories of the former Soviet Union. Moreover, in 1933, Stalin personally sanctioned the shipment of grain to Ukraine, to the detriment of several Russian regions.

More than 630,000 citizens of Leningrad perished in the famine during the Blockade of Leningrad by German and Finnish forces, lasting 872 days. The population had consumed the city’s entire population of cats and dogs, transitioning to birds and bird feed, medications, sunflower cakes, wood glue, animal hides and leather belts, which were boiled. “My sensations felt dumbed down. I walk across the bridge. In front of me, slowly staggering, walks a tall man. Another step, and he falls down. I simply walk past him, lying there, dead - I don’t even care. I enter my building, but can’t ascend the steps. So I take one leg with both hands and place it on a stair. Then the next on the following one…,” Tatyana Aksenova remembered.

The famine of 1946-47 was the result of the destructive World War II, and the subsequent drought of 1946, which brought about low crop yields. Nonetheless, tragedy could have been averted (the USSR had vast grain reserves) had it not been for the catastrophic decision to increase grain exports by almost twice the pre-war quantities. Aside from that, cautious of another war - this time with former allies, management was trying to preserve its agricultural reserves, and denied any produce to the regions - all while never reducing its demand for them. The resulting famine annihilated 1.5 million people.

“We walked the villages, begging, weren’t having much luck, no one had had a sweet life back then,” remembers Aleksandra Lozhkina, an inhabitant of the Povolzhye region: “I remember coming home once with what little I had managed to gather. My mother was lying on the big stove with my brother and sister, and they’re not moving. I managed to bring my mother to her senses, gave her a piece of bread, and she got up. We fired up the stove, she made us all something to eat, and then told me: ‘Shura, give me another piece of bread.’ This was the first time she’d asked for bread, having given everything to us. We only ‘came alive’ when the first greenery appeared: grass, nettles, sorrel, goosegrass, followed by mushrooms and berries.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox