Why didn't Stalin rescue his son from German captivity?

"I am ashamed before my father that I remain alive," Yakov Dzhugashvili, the son of Joseph Stalin, told the Germans during interrogation. The Soviet supreme leader, who had a very negative attitude to Red Army soldiers who surrendered, faced one of the most difficult situations in his life — the enemy had captured his own son.

Difficult relations

Yakov was Stalin's son from his first marriage, to Ekaterine (Kato) Svanidze. As his mother died soon after giving birth to him, and his father spent all his time either in revolutionary struggle or in exile, the child was brought up by an aunt.

In 1921, at the age of 14, Yakov Dzhugashvili (who used Stalin’s real family name) moved from Georgia to Moscow, where he met his father for the first time. Relations between the two, who essentially knew nothing about each other, were difficult.

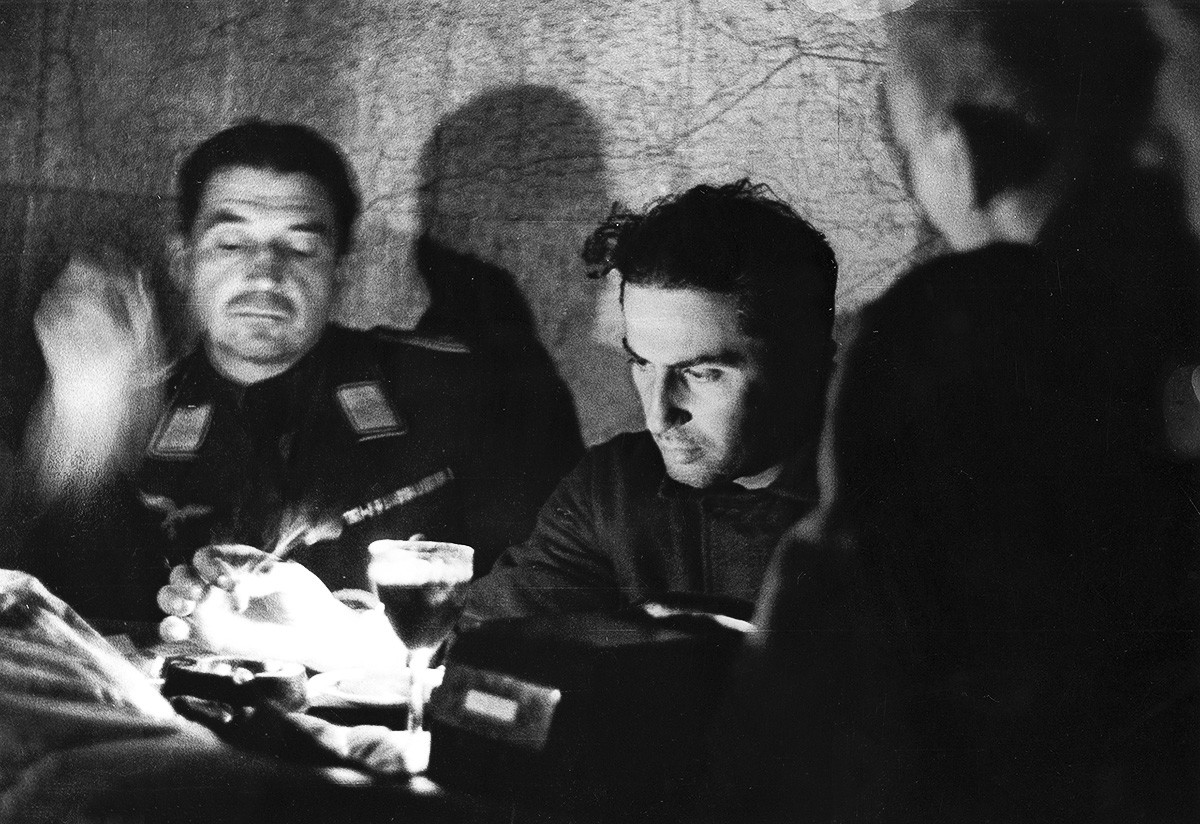

Yakov Dzhugashvili (R).

Archive photoStalin was categorically against Yakov's first marriage and this provoked a major row between father and son. Added to this was Dzhugashvili's personal tragedy — the death of his infant daughter. In the end, he tried to shoot himself, but didn't succeed and only survived thanks to the efforts of Kremlin doctors.

The Soviet leader's elder son didn't always oppose his father in everything. A turbine engineer by profession, on his father's insistence Yakov enrolled in the Red Army Artillery Academy. In May 1941, a month before the German invasion of the USSR, Senior Lieutenant Yakov Dzhugashvili was appointed commander of an artillery battery.

Captivity

When the war started, the Soviet leader did nothing to shield his son from the war. The latter went to the front line as an ordinary Red Army commander attended by his father's simple words of parting: "Go and fight".

But Yakov did not end up fighting for long. In early July 1941 units of his 20th Army surrendered in Belorussia, and on July 16, during an attempt to break out and reach his own side, Senior Lieutenant Dzhugashvili was captured.

The Germans very quickly realized who had fallen into their hands - Yakov was betrayed by several of his fellow servicemen. The Nazis had no intention of staging a public execution of the son of their arch-enemy. On the contrary, it was in their interests to entice Dzhugashvili to their side, use him in their propaganda campaigns and play off "Stalin" Junior against Stalin Senior.

Yakov was treated with civility and courtesy. At his interrogations the Germans did not just inquire about military matters but also about his political views. They argued about Stalin's methods of running the state, pointed out to the son the mistakes of the father, and emphasized the shortcomings of the ideology of Bolshevism. They did not get anywhere in their attempts to "soften up" the prisoner of war, however, and Dzhugashvili refused to cooperate with the Germans in any way whatsoever.

At the same time, the Third Reich’s propaganda machine ensured that news of the capture of the son of the all-powerful Stalin became common knowledge in the USSR. Despite the fact that Dzhugashvili particularly stressed in his interrogations that he had been taken prisoner against his will, the Germans explicitly declared that his surrender had been entirely voluntary. Initially, Stalin himself believed this version of events.

A soldier for a field marshal

As a result of information that filtered through to the Kremlin about the circumstances of his son's imprisonment and details of his conduct in captivity, Stalin soon changed his opinion of Yakov and no longer regarded him as a traitor and coward.

Several rescue missions were organized to get Dzhugashvili out of German hands. Spanish Communists who had been forced to flee Spain in the wake of defeat in the Civil War and were now living in the Soviet Union were even recruited for the operations because of their valuable experience of guerrilla and partisan warfare. But all attempts to free Yakov came to nothing.

After the battle of Stalingrad, the Germans used the mediation of Swedish diplomat Count Folke Bernadotte and the Red Cross to offer Stalin an exchange of his son for Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus and several dozen high-ranking 6th Army officers held in Soviet captivity. Hitler promised the German people to bring the generals home.

Today, we can only speculate about what Stalin thought about such an exchange. The established view in the Soviet Union in the post-war period was that the Soviet leader replied icily to the German proposal: "I won't exchange a soldier for a field marshal." There is no documentary confirmation, however, that he actually uttered this phrase.

The supreme leader's daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, recalled that a little after these events, in the winter of 1943-44, her agitated and incensed father referred to the failed deal: "The Germans proposed exchanging Yasha for some of their people… Was I to start bargaining with them? No, war is war."

Yakov Dzhugashvili during his interrogation after his capture.

Getty imagesMarshal Zhukov wrote in his Memories and Thoughts that once, when they were out walking, he had asked Stalin about his elder son. He replied pensively: "Yakov won’t get out of captivity. The Fascists will shoot him…" After a pause, he added: "No, Yakov would prefer death to betraying the Motherland."

True enough, Dzhugashvili continued to be defiant, and what had started off as good treatment on the part of the Germans rapidly became extremely harsh. The upshot was that, unable to exploit him either for propaganda purposes or to make a prisoner swap, they lost all interest in him.

On April 14, 1943, Yakov threw himself at the electrified barbed wire in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and was immediately shot dead by a guard. Whether he wanted to commit suicide or to escape, or whether his death was organized by the Germans themselves, remains a mystery to this day.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox