How Russian Cossacks became elite troops of the Chinese emperor

The battle for the Far East

In the middle of the 17th century, the Russian and Chinese civilizations, which until then only had a very vague idea of each other, met on the battlefield for the first time. It occurred when Cossack detachments reached the banks of the River Amur, which was inhabited by the Daur tribes who paid tribute to Beijing.

The Qing Empire saw the arrival of the “barbarians from afar” in the land of its tribute-payers as an invasion of its zone of interests. Considerable forces of Chinese and Manchus (the Manchu dynasty came to the throne of China in 1644) were sent to fight the Russians. The main confrontation was over the stockaded settlement of Albazin, which was gradually becoming Russia's main outpost in its conquest of the Far East.

When, in June 1685, a 5,000-strong Qing army approached Albazin, its garrison consisted of only 450 men. Despite their tenfold superiority in manpower and artillery, the Chinese and Manchus were much inferior to the Cossacks in their level of combat training. The Russians successfully held out for a long time, until it became clear there was no point in waiting for outside help.

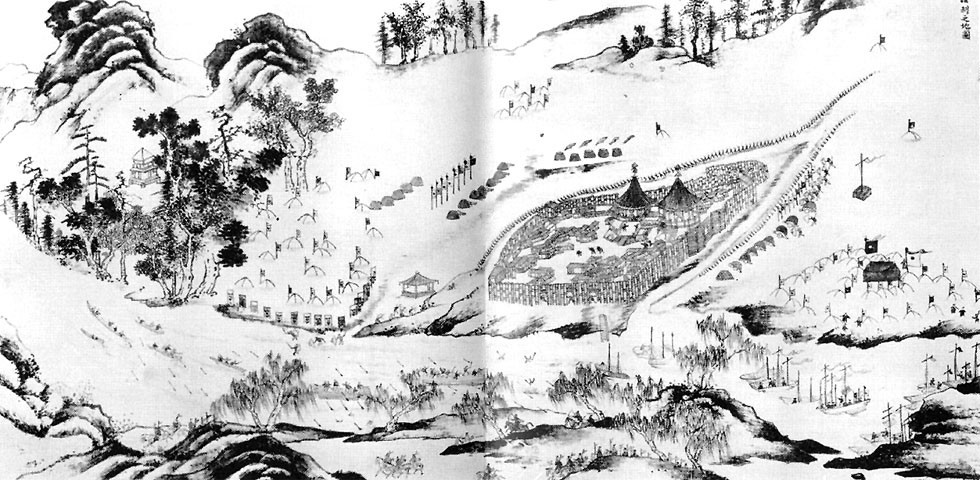

Siege of Albazin. Chinese painting of the 17th century.

Library of CongressUnder honorable surrender terms, the Albazin garrison were allowed to leave and return to their own side. However, the Chinese offered those apprehensive of the long and difficult journey home to come over to the service of the Chinese for a good remuneration. Forty-five Cossacks expressed a desire to serve the emperor.

The best of the best

It was Emperor Kangxi’s own idea to entice the Russians over to his side. From the very first clashes with them he realized that the Russians were a dangerous and strong enemy and it would be difficult to drive them out of the Far East. The emperor decided he needed fighters like them, so, whenever possible, he happily incorporated them into his own army.

This policy led to more than a hundred Russians in total joining the army of the Qing Empire. Some did it of their own free will, while others were captured as prisoners in military campaigns and then decided to stay in a foreign land. All of them went down in history as ‘Albazinians’ after the largest group of volunteers from the fort on the River Amur.

The Cossacks were treated with great honors. They were ranked among the hereditary military class, which was almost at the top of the social structure in Qing Dynasty China. Only the privileged nobility were above them.

Emperor Kangxi.

Public DomainThe Albazinians were enrolled in an elite contingent of Qing troops under the direct command of the Emperor — the so-called ‘Bordered Yellow Banner’ (there were eight banners in total, each numbering up to 15,000 soldiers). Within the banner, they had their own “Russian company” — ‘Gudei’.

Apart from the Russians, only aristocratic Manchu youths were allowed to join the Bordered Yellow Banner guards unit. The Chinese were barred from it.

A comfortable life

The Albazinians were showered with privileges: They were provided with housing and arable land and received monetary payments and rice rations. Those who had no families (i.e. the majority) were given local Chinese and Manchu women — the widows of executed criminals — as wives.

The Chinese did not encroach on the religious faith of their Russian soldiers. On the contrary, they allowed the Cossacks to use an old Buddhist prayer house and convert it into an Orthodox church. Until then, the Cossacks had had to go to the Chinese capital’s Roman Catholic South Church to pray.

Albazinian liturgy in Beijing in the 19th century.

Public DomainOrthodox Christianity gained a foothold in China precisely thanks to the Albazinians and, in particular, Father Maxim Leontiev, who also arrived in Beijing after the surrender of the Amur fort. As the first Orthodox Christian priest in the country, he performed all divine services — baptisms, marriage ceremonies and funeral services for his fellow believers and participated in all the affairs of the Russian colony in the Chinese capital. “He revealed the light of Christ’s Orthodox faith to them [the Chinese],” Metropolitan Ignatius of Tobolsk and Siberia wrote about him.

Still, the Cossacks were not recruited in order to lead an idle life. There is evidence of their participation in several campaigns by Qing troops, in particular against the Western Mongols. Also, Albazinians were used for propaganda purposes — to persuade former compatriots to join the emperor’s cause.

Decline

Over time, China and Russia settled their border conflicts and the military and political importance of the “Russian company” in the Bordered Yellow Banner began to diminish. Its tasks were mainly reduced to garrison duties in the capital.

Having integrated with the local Chinese and Manchu population, after several generations the Albazinians lost all their Russianness. Nevertheless, they continued to practise the Orthodox faith and often boasted of their privileged position. According to Russian travellers who visited Beijing at the end of the 19th century, the Albazinian “in the moral sense is a parasite living on handouts at best and a drunk and a cheat at worst”.

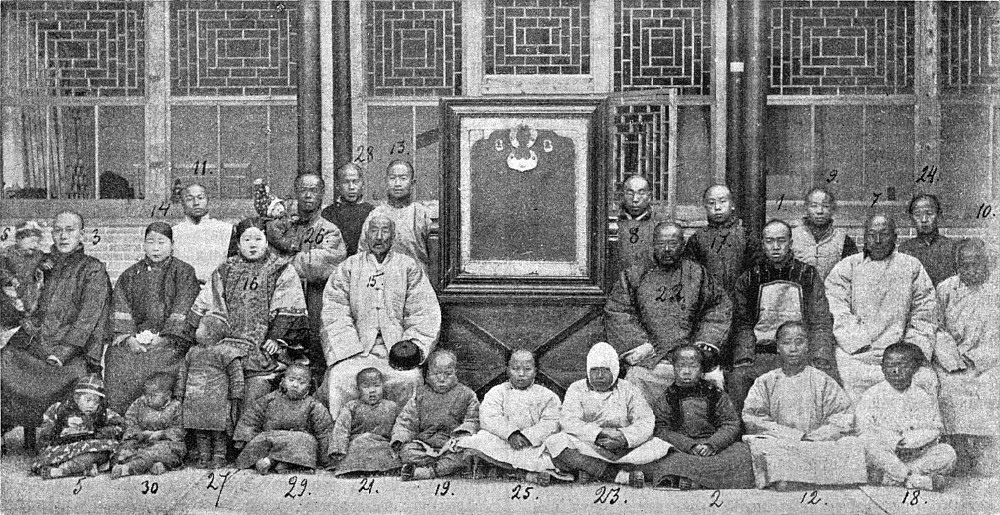

Descendants of the Albazinians in 1900.

Public DomainA serious ordeal for the Chinese Cossacks was the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 against foreign domination and Christianity. Several hundred Albazinians became its victims — but even in the face of death, they refused to renounce their faith.

After the fall of the Qing Empire in 1912, the descendants of the Cossacks were forced to look for new occupations in life. Many of them became police officers, or worked for the Russo-Asiatic Bank and the printing press at the Russian Spiritual Mission.

Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, directed against everything foreign in China, dealt another blow to the Albazinian diaspora. As a result of persecution, many of its members were forced to renounce their roots.

Nevertheless, even today in modern China, there are people who regard themselves as the descendants of the Albazin Cossacks — the emperor’s elite soldiers. They are not familiar with the Russian language and it is impossible to distinguish them from the Chinese. However, they still cherish the memory of where they come from.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox