Why the most renowned Soviet female pilot never became a general (PHOTOS)

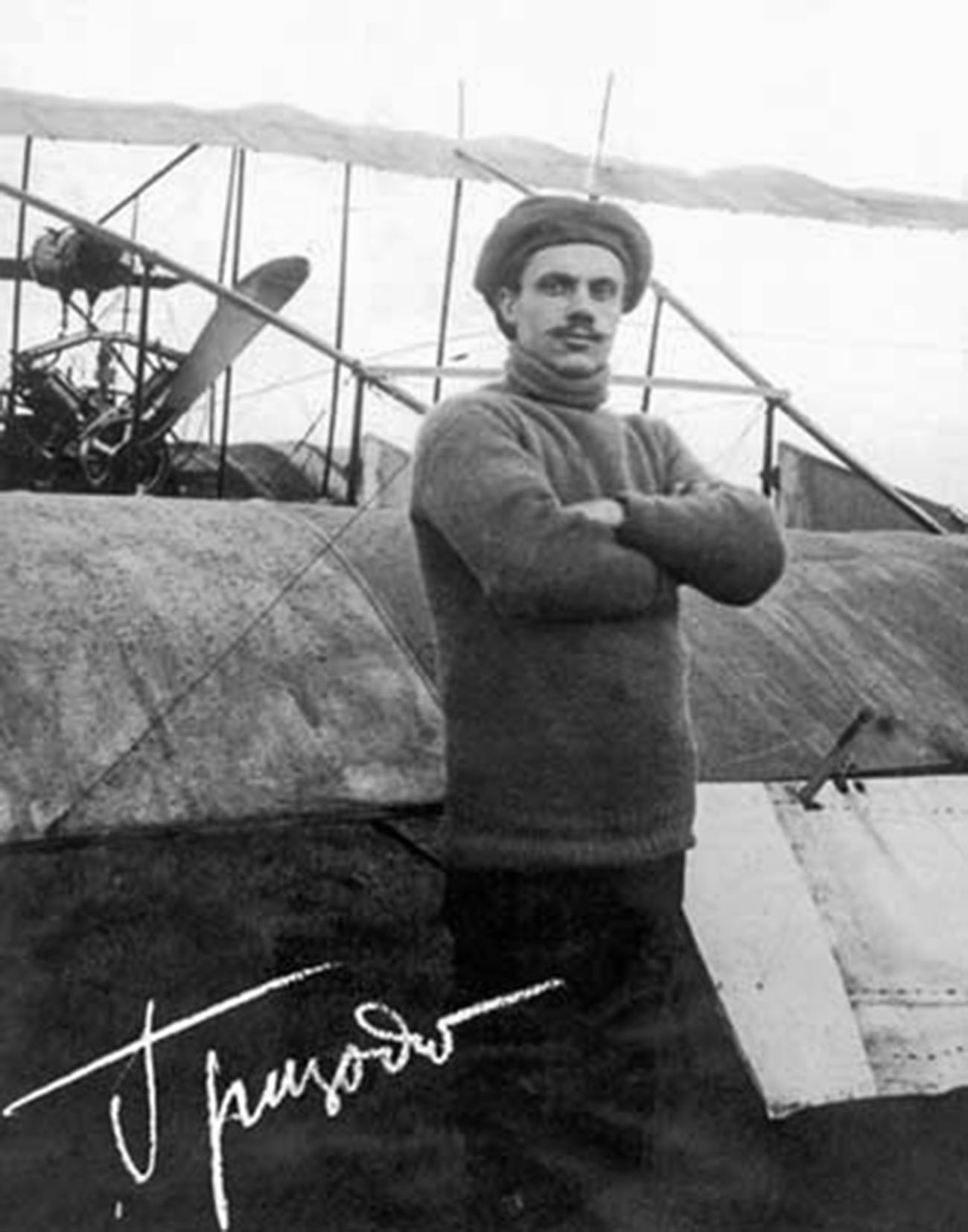

Valentina Stepanovna Grizodubova's life was inextricably linked to aviation since her early childhood. Her father, Stepan Grizodubov, was one of the pioneers of the Russian aircraft industry. In 1912, when she was just two years old, he took her on her first flight. “From early childhood, she had a resolute and persistent character. For a girl, it was simply heroic,” the father later said.

Stepan Grizodubov.

Public DomainAfter successfully completing training at a flying club and a school for instructor pilots, Grizodubova in 1929 joined the Gorky Agit-Squadron. Its propaganda planes performed flights all over the country, distributing communist literature, showing films, organizing meetings with scientists, artists, and party officials. For many people in remote parts of the country, that was the first time they saw an aircraft. Needless to say, they were equally amazed to see that it was piloted by a woman.

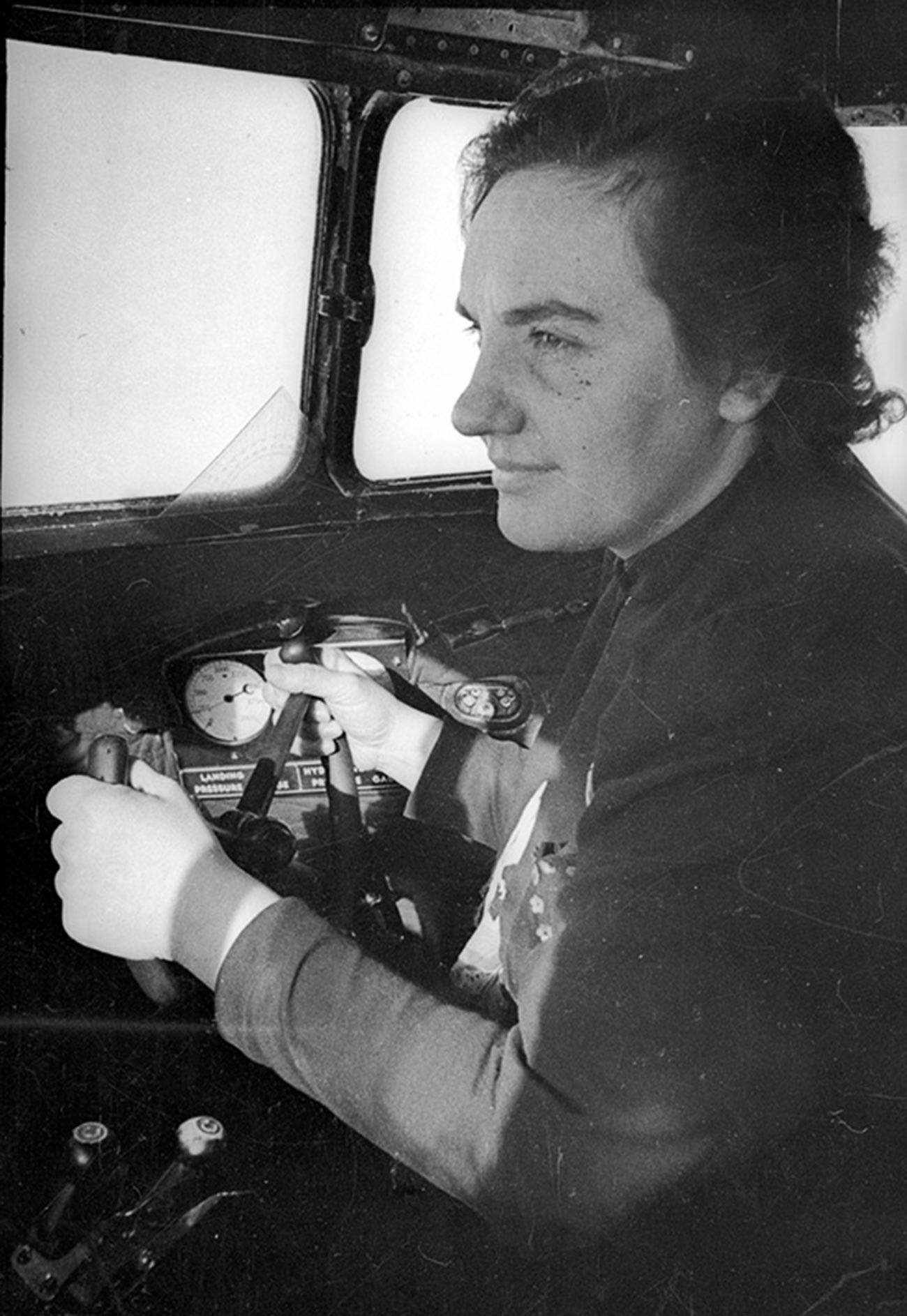

Valentina Grizodubova.

Evgeny Khadley/МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruGrizodubova first became famous in 1937, when she set five world records in altitude, range and speed among women in a light aircraft. However, she only gained celebrity status the following year after her famous non-stop flight on an ANT-37bis bomber across the country, from Moscow to the Far East.

Pilots Larisa Rozanova (L) and Valentina Grizodubova.

Georgy Lipskerov/МАММ/МDF/Rybchinsky and Gladkov Fund/russiainphoto.ruOn September 24-25, 1938, a Rodina plane with pilot Grizodubova, co-pilot Polina Osipenko and navigator Marina Raskova covered a distance of 6,450 km in severe weather conditions in 26 hours 29 minutes, setting a flight range record for a female crew. Unfortunately, due to high clouds, they made a navigation error. Having veered off course, the plane wasted a lot of fuel. Unable to reach the landing strip, Valentina Stepanovna landed the aircraft in a swamp in the taiga, 70 km from the nearest settlement. The crew was discovered after nine days of searching.

Pilot Grizodubova (C), co-pilot Polina Osipenko (L) and navigator Marina Raskova.

Alexander Ustinov/Ninel Ustinova's archive/russiainphoto.ruBack home, Grizodubova, Osipenko and Raskova received a hero's welcome. They became the first women to be awarded the title of Heroes of the Soviet Union. “Had it not been for these three remarkable women, jokes comparing women’s brain to that of a chicken would have probably been doing the rounds longer, and inveterate skeptics who believed that women and aviation were incompatible would not have had their smirks wiped off their faces,” pilot Marina Chechneva wrote later.

The welcome ceremony for the Rodina plane crew.

Alexander Ustinov/Ninel Ustinova's archive/russiainphoto.ruValentina Grizodubova left a mark not only in aviation. As a member of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, she devoted a lot of time and effort to looking into the cases of victims of repressions. Using her authority and influence, Valentina managed to get many cases reviewed and many people's sentences reduced. For example, thanks to her intervention the future “founding father" of the Soviet space program, Sergei Korolev, was transferred from a Kolyma gulag camp to the special design bureau, TsKB-29, where convicted scientists could do research “for the benefit of the working people”.

In 1942, at the height of the Great Patriotic War (as the fighting on the Eastern Front during World War II is known in Russia), Grizodubova became the commander of the 101st Long-Range Aviation Regiment that consisted of male pilots. Their initial skepticism soon gave way to respect. Grizodubova showed herself both as a skilful manager and combat commander: she performed 200 sorties, including 132 night flights.

"On more than one occasion I had an opportunity to become further convinced that my commander, a woman who had never served in the Armed Forces before, turned out to be superior to me in the ability to organize flight operations and in training bomber crews. She was fully prepared to lead the regiment's combat activities,” the regiment's chief of staff Alexander Verkhozin recalled. Soldiers even gave Grizodubova the nickname ‘Mother’, although she was in her early 30s at the time.

One special task given to Grizodubova's regiment was to deliver supplies to partisan detachments operating behind enemy lines. Often, the commander herself went on dangerous missions, for which she was later awarded a Partisan of the Patriotic War 1st class medal. “A very brave woman, decisive and daring in carrying out what was planned,” Alexander Saburov, commander of a partisan unit operating in Ukraine, wrote after the war. “Having returned to Moscow, Grizodubova, with her usual persistence, achieved a lot. A proper air bridge was established between us and the mainland. We began to receive cargoes in a steady flow.”

And yet, Valentina’s career did not escape some unpleasantness. In 1944, she had a conflict with the commander of Long-Range Aviation, Alexander Yevgenievich Golovanov. According to his version, Grizodubova, using her connections, directly appealed to Stalin with a complaint against her superior and a request to promote her to the rank of general (she was a colonel), and grant her regiment the title of ‘guards’. “Blinded by the possibilities that had opened to her, regiment commander Grizodubova did not give a minute's thought to what might befall those people she was maligning. Instead, she already saw herself as the first woman in the country to try on a general's uniform...,” Golovanov recalled.

Alexander Golovanov.

Archive photoDespite pressure from above, Alexander Golovanov flatly refused to concede to Grizodubova. Furthermore, he accused her of poor discipline in her regiment and of a large number of flight accidents not related to combat missions. Golovanov also added that Grizodubova was often absent from her unit without a valid reason. After lengthy disciplinary proceedings, the commission hearing the case sided with the commander of the Long-Range Aviation. “For slandering her immediate superiors for selfish purposes, for an attempt to slander Marshal Golovanov”, Grizodubova's case was referred to a military tribunal.

Valentina Grizodubova and aeronautical engineer Andrei Tupolev.

Dmitry Chernov/TASSIn the end, the case never went to a tribunal, but Valentina still had to leave the Armed Forces. In subsequent years, she made a noticeable contribution to the development of electronic equipment for military and civil aviation. In 1986, Grizodubova was awarded the title of a Hero of Socialist Labor.

Valentina Stepanovna never commented on the circumstances of her conflict with Marshal Golovanov, so we only know his side of the story. What’s certain is that Grizodubova did dream of becoming the world’s first female general of aviation and was very sorry that it never materialized.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox