How Chinese soldiers helped Bolsheviks to hold on to power in Russia

First Red Army's Chinese unit in Petrograd, 1918.

Sputnik“A Chinese [soldier] is tough, he is not afraid of anything. His brother may be killed in battle, but he will not bat an eye... If he understands that he faces an enemy, the enemy is not to be envied. A Chinese [soldier] will fight to the very last,” Soviet commander Iona Yakir wrote in his Memoirs of an Old Red Army Soldier.

More than 40,000 Chinese soldiers fought in the Russian Civil War on the side of the Red Army. What was it that prompted them to get involved in somebody else’s conflict on somebody else’s land?

Under the banners of the revolution

In 1917, Russia had an ethnic Chinese population of almost 200,000 people, most of whom were doing menial jobs in industry, agriculture and construction. The tsarist government sought to resolve workforce shortages resulting from World War I by recruiting cheap labor in China.

First Red Army's Chinese unit in Petrograd, 1918.

SputnikHowever, when the Civil War began and the Bolsheviks came to power, the Chinese in Russia found themselves in a difficult situation. As the country was plunging deeper and deeper into chaos, there were not many opportunities for them to make a living. When Siberia, as well as the northern and southern ports, fell under the control of the White Guard and the Allied troops, the road home was cut off for the Chinese population of central Russia. Furthermore, not all of them wanted to go back to China, which at the time was going through the so-called Warlord Era and was being torn apart by military and political cliques.

Thus, perhaps the only way for the Chinese proletariat, who had accumulated in large Russian cities, to feed themselves and their families and to earn enough money for a journey home was to enlist in the Red Army. “The Chinese took their pay very seriously. They gave their lives easily, but demanded to be paid on time and to be fed well,” Yakir recalled.

And yet, money was not the only reason why thousands of Chinese enlisted under the red banners. Many of them had an affinity with the ideology of a socialist revolution and communism. “Tsarist Russia and China, with its ruling Qing dynasty, were not very far apart: in both countries the rich lived in luxury and ease, while the poor lived in hunger and cold,” soldier Chen Bo-chuan wrote in his memoirs Days and Nights in Siberia.

Soldiers of the 225th Chinese International Regiment.

МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruBolsheviks were well aware of the sentiments prevalent in the Chinese community and targeted them with relentless propaganda, urging them to join in the efforts to build a new and just world order. In large cities, there appeared newspapers in Chinese with titles such as ‘Great Equality’, ‘Communist Star’, ‘Chinese Worker’ and others. Members of the Chinese community were pleasantly surprised to learn (through Bolsheviks’ media efforts) that Lenin had voiced strong criticism of how the Boxer Rebellion against foreign domination in China in the year 1900 had been suppressed by the great powers.

As a result, tens of thousands of Chinese volunteers joined the ranks of the Red Army. Some hoped to earn a piece of bread, others dreamed of making their way back home, others were inspired by ideas of a world revolution and still others were not averse to taking advantage of the turmoil that reigned in Russia to engage in some robbery and plunder.

Red Guard

The Chinese soldiers quickly earned the reputation of some of the most disciplined and effective in the Red Army. They could not desert and mix among a foreign population in a foreign country, so their loyalty was unquestioned. “Chinese soldiers always treated their duties extremely honestly and conscientiously and therefore won great trust from commanding officers,” soldier Zhang Zi-xuan wrote in his memoirs Shoulder to Shoulder.

Ren Fuchen (center, white coat) with his soldiers.

Public Domain“All of them are brave warriors, but they cannot stand one thing, the glint of steel,” party leader Yakov Nikulikhin recalled in his book At the Civil War Front: “The Cossacks were aware of that and on sunny days before an attack they would start waving their unsheathed swords. This filled the Chinese with panic and they ran away to hide in a sunflower field. But generally speaking, a Chinese Red Army soldier is brave, he does not retreat when faced with machine-gun fire and fights courageously.”

The Whites particularly resented the Chinese in the Red Army, along with other foreigners in its ranks: Latvians, Estonians, Hungarians. “Savages, infidels and German spies” were considered one of the main pillars of Bolshevik power and, when they were taken prisoner, they were usually shot on the spot.

From Poland to the Pacific Ocean

The Red Army’s 40,000 Chinese soldiers never acted as a single force. Instead, they were split into detachments of not more than 2,000-3,000 soldiers in each and incorporated into larger units scattered across the country. Thus, there were Chinese servicemen in the 25th Rifle Division of the legendary Red commander Vasily Chapayev and even in Lenin’s personal guard.

One of the strongest and most reliable Red Army units in the Urals and Siberia was the 225th Chinese International Regiment under the command of Ren Fuchen. After his death on November 29, 1918, he was posthumously awarded an Order of the Red Banner and Lenin personally met with his widow and children.

About 500 Chinese cavalrymen served in the Bolsheviks’ best military unit, the 1st Cavalry Army of Semyon Budyonny. During the Soviet-Polish war, an enemy counterattack on the Vistula cut them and a part of the army off from the main forces, forcing them to retreat to German territory, where they were interned. The Germans kept the Chinese separately, trying to persuade them to remain in their service, but the Chinese refused and soon returned to Russia together with the other prisoners.

In the Russian Far East, one of the most famous Chinese units was the partisan detachment of communist San Di-wu, which successfully fought against the local White Cossack troops, Japanese and American invaders, as well as Chinese bandits, the Honghuzi. Their leader was known for his exceptional courage: he often engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the enemy, was wounded four times and even derailed an American steam locomotive once.

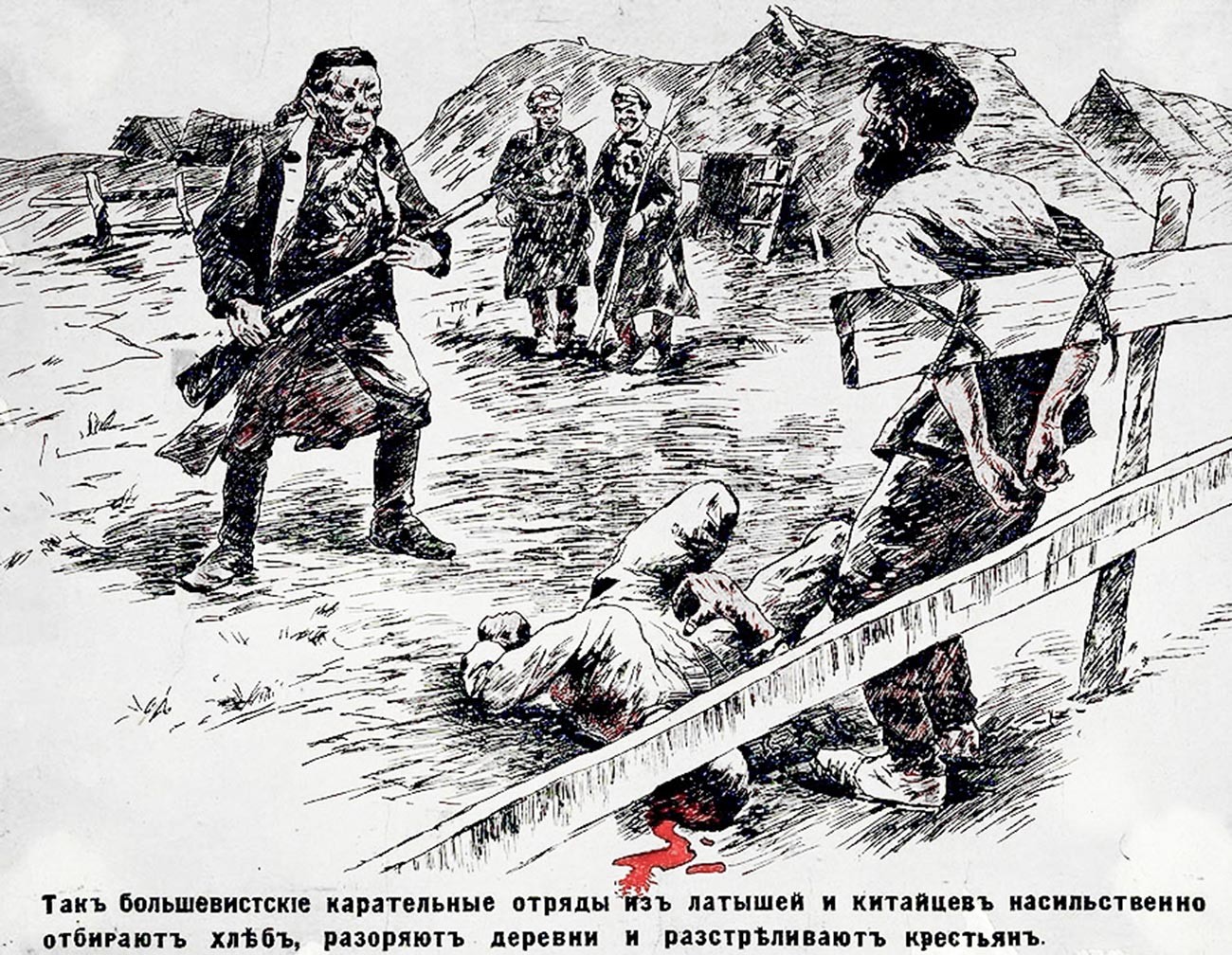

Chinese soldiers on the White movement poster 'Sacrifice to International.'

Public DomainThe Chinese fought on the side of the White Guard, too. There were instances when, having come across their fellow countrymen in the Red Army at the front, they, without hesitation, went over to their side.

Punitive operations

The Chinese soldiers’ iron discipline manifested not only in battle. Their diligence and unquestioning obedience to orders came in particularly useful in carrying out punitive actions and executions. Where Russians might flinch, Chinese soldiers acted with precision and without emotion.

Not all of them were communists and hated their class enemies. Many treated clashes with the enemy and executions of rebellious peasants and workers with the same indifference, as routine work for which they received a salary.

Poetess Zinaida Gippius, who prior to her escape from Soviet Russia at the end of 1919 lived in Petrograd (St. Petersburg), wrote in her diary: “Do you know what Chinese meat is? Here’s what it is: as you know, chekists give the bodies of executed White Guards to animals at the zoo... The executions are carried out by the Chinese. Both here and in Moscow. During the executions and when sending the bodies to the zoo, the Chinese are engaged in looting. They do not release all the bodies but hide those that are younger and then sell the meat as veal... Dr. N. bought a slice of meat ‘on a bone’ and identified the bone as a human one... In Moscow, a whole family ended up with upset stomachs…”

White movement propaganda poster depicting Red Chinese and Latvian soldiers.

Public Domain“A quick attack by infantry scouts and the 1st Battalion defeated the Chinese,” White Guard officer Anton Turkul recalled. “About 300 were captured. Many had gold wedding rings on their fingers taken from the executed and cigarette cases and watches in their pockets, also taken from those who had been executed. The Cheka’s Asian executioners, with their rat-like stench, their felt-like black hair and flat dark faces, had riled our soldiers. All the 300 Chinese soldiers were shot.”

After the war

After the Civil War was over, the Chinese personnel continued to serve in the Soviet police, the Red Army and the security services. They fought bandits, guarded the routes along which food was delivered to the starving provinces during the 1921-1922 famine, in which up to five million people died.

Hundreds of them decided to stay in the Soviet Union for good. They married Russian women and found themselves jobs in industry and agriculture. For example, Cha Yan-chi, having trained as an agronomist, did a lot to develop rice growing in the North Caucasus.

Mao Zedong in 1939.

Public DomainHowever, most of those who made up the Red Army’s Chinese contingent returned to their homeland. With a wealth of combat experience and additional specialized training, they went home to help Mao Zedong establish Soviet rule there and soon became the core of the Chinese Communist Party.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox