Russia's most infamous traitors

Andrey Vlasov in 1943.

Getty Images1. Ivan Mazepa

Portrait of Ivan Mazepa.

Dnipropetrovsk Art MuseumIvan Mazepa was one of the few people who enjoyed Peter the Great's unconditional trust. As hetman (ruler) of Left-bank Ukraine, which was then part of Russia, he faithfully served the Russian monarch for many years, and for which he received the highest state award - the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle – from the hands of the tsar himself.

That all changed with the Northern War (1700-1721), which at first was not going well for Russia. The dire situation induced Mazepa to consider leaving Moscow's orbit and creating an independent Ukraine where he would be ruler. After secret negotiations with King Charles XII of Sweden, the hetman openly sided with the Swedes in October 1708.

Charles XII and Ivan Mazepa after the Poltava Battle.

Gustaf CederströmPeter immediately stripped Mazepa of all titles and regalia, while the Russian Orthodox Church excommunicated him. Most of his Cossacks did not support the hetman and remained loyal to the Russian tsar. When on July 8, 1709, Swedish troops, together with Mazepa's men, were defeated near Poltava, the hetman had to flee to the Ottoman Empire, where he died on October 2 of the same year.

2. Genrikh Lyushkov

Genrikh Lyushkov.

NKVD archiveGenrikh Lyushkov was one of the highest-ranking defectors in all of Soviet history. A top level State Security Commissioner and head of the NKVD's Far Eastern Directorate, he secretly escaped by crossing the border into Japan’s puppet state of Manchukuo in the early morning of August 13, 1938.

During the period of large-scale political reprisals in the USSR known as the Great Purge (1936-1938), Lyushkov was busy fighting against “enemies of the people” in the Far East. As a result of his activities, a wave of arrests swept through the army, the NKVD, the Party apparatus and the Pacific Fleet.

As was often the case at the time, however, soon the accuser himself became the accused. In May 1938 Lyushkov was recalled to Moscow, and he realized that a trial and execution most likely awaited him there. So the commissar decided to flee.

A special unit of the Japanese Imperial Navy.

Public DomainGenrikh Lyushkov supplied the Japanese with unique and detailed information about the number and deployment of Soviet troops in the Far East, the location and condition of defense fortifications, military codes, the NKVD's internal procedures, opposition sentiments in the region and in the armed forces, and so on. On the basis of such information, the General Staff of the Imperial Japanese Army adjusted its strategy for a future war with the USSR.

Lyushkov, however, did not live to see the end of the Second World War. The Japanese did not want the former commissar, who had learned a lot about Japanese intelligence, to fall into the hands of the USSR. On August 19, 1945, he was executed.

3. Andrey Vlasov

Andrey Vlasov in 1942.

BundesarchivBefore he became the No. 1 Soviet traitor, Andrey Vlasov was considered a talented and promising military leader. In 1939, he served as a chief military adviser in China, and Chiang Kai-shek even awarded him with the Order of the Golden Dragon.

During the first catastrophic months of the war against Germany, Vlasov acted courageously and effectively. The 20th Army under his command played a significant part in the defeat of the Germans near Moscow in December 1941.

In 1942, Lieutenant General Andrey Vlasov was put at the helm of the 2nd Strike Army, which in the summer of the same year was surrounded by the enemy near Leningrad. The commander himself was captured and sent to a POW camp. There he decided to cooperate with the Germans.

Andrey Vlasov with ROA soldiers.

BundesarchivFor the Nazis, Vlasov turned out to be a valuable asset. An illustrious Soviet general who went over to Hitler's side played an important part in the propaganda war. Furthermore, he spent much effort agitating among Soviet prisoners of war, trying to get them to join him in the fight for "a New Russia without Bolsheviks".

The No. 1 traitor's main goal was to unite all the units of Russian collaborators into a single Russian Liberation Army (RLA), with himself as its commander. The leadership of the Third Reich, however, was highly suspicious of the idea of setting up a large army of Soviet prisoners of war and delayed the process. Vlasov was given a free hand only at the end of 1944, when the fate of the Nazis was generally a foregone conclusion. As a result, the RLA never became a significant military force.

The general was captured in Czechoslovakia by Soviet troops on May 12, 1945 as he was trying to break through to the west, to reach the approaching American troops. Together with a group of his followers, Vlasov was accused of high treason and hanged in Moscow on August 1, 1946.

4. Oleg Penkovsky

Oleg Penkovsky.

Tikhanov/SputnikIn 1960, Oleg Penkovsky, a colonel with the Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff of the USSR Armed Forces, asked a group of American tourists in Moscow to pass a letter to the U.S. Embassy whereby he offered his services in collecting classified information for the CIA.

The following year during a business trip to London, MI6, the British secret intelligence service, provided Penkovsky with the necessary spy equipment, including a portable camera and special radios. The colonel was given the codename “Hero”.

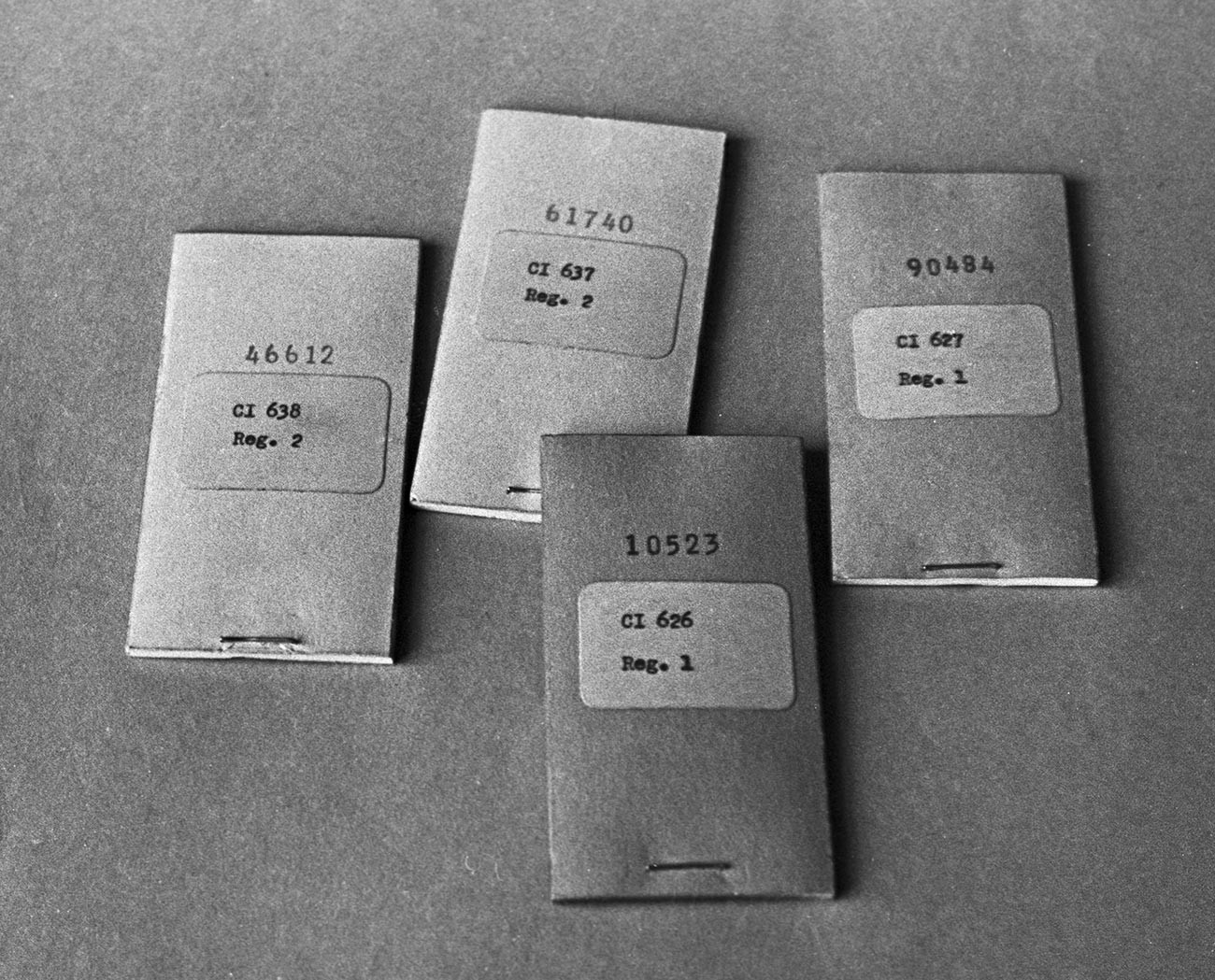

Oleg Penkovsky's stuff.

Boris Prikhodko/SputnikOne of the most successful Western agents in the USSR, Oleg Penkovsky supplied the American and British secret services with 11 films that had 5,500 documents containing a total of 7,650 pages of classified information about the Soviet armed forces. He also betrayed nearly 600 Soviet intelligence officers to enemy spy agencies.

In 1962, Penkovsky was exposed and arrested by the KGB. He was convicted of high treason and shot on May 16, 1963.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox