What did the Soviets plan to do if the Nazis captured Moscow in 1941?

In mid-October 1941, Nazi troops were rapidly approaching Moscow. The Soviet cities that surrounded Moscow were, one by one, falling to the enemy. The Germans could have entered Moscow at any moment.

So, on October 15, 1941, Stalin — known for his propensity to wake up late and work late hours — addressed his Politburo associates at 9 am. They were ordered to organize the evacuation of the city and leave the capital by the evening of that very day.

The new capital

The city of Kuibyshev (present-day Samara) was to be their destination. Located 700 miles (1,100 kilometers) east of Moscow, Kuibyshev was a natural choice for the role of the new capital of the USSR for several reasons.

An anti-aircraft crew near the Gorky Park in Moscow, 1941.

Naum Granovsky/SputnikRelative proximity to Moscow facilitated the evacuation of the capital. It did not take too long for the state bodies, factories and administrative institutions vital for the functionality of the USSR to arrange and resume their work at the new place.

Kuibyshev was also relatively well-protected by a large group of troops stationed there. The headquarters of the Soviet Volga Military District was already based in the city. The city was also known as an industrial powerhouse of the USSR that accommodated factories, airfields and a vital railway hub.

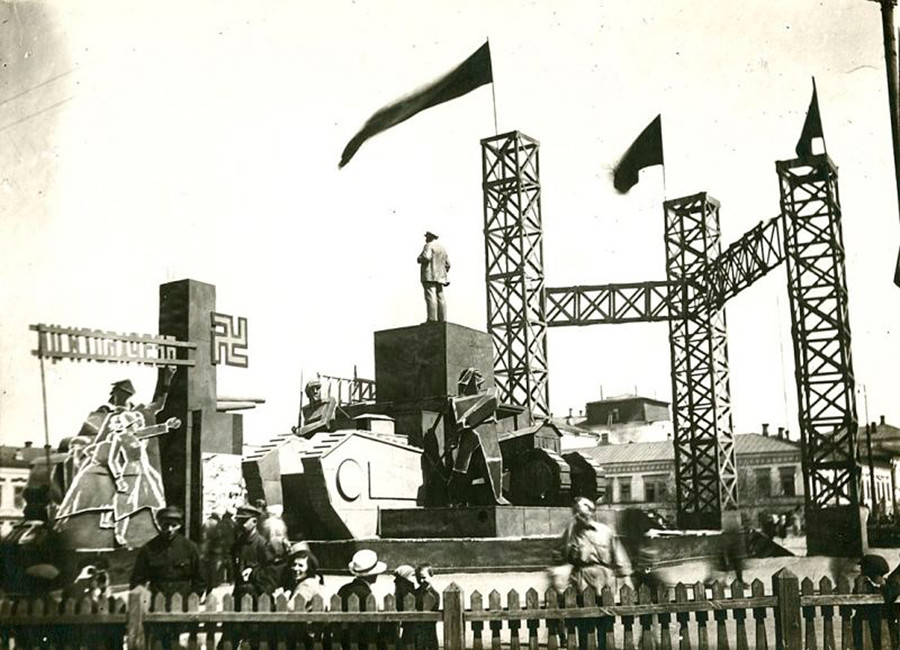

Kuibyshev, 1931

Samara Regional Art MuseumOn the fateful morning of October 15, 1941, the Soviet State Defense Committee, headed by Stalin, passed the top-secret resolution #801. It prescribed that the General Staff and the People’s Commissariat of Defense, People's Commissariat of the Navy, the diplomatic corps, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR all move to Kuibyshev, effective immediately.

Stalin, who considered he himself might need to leave Moscow soon, gave himself one more day in the capital. His closest associates — Beria, Mikoyan, and Kosygin — stayed in Moscow, as well.

Stalin addresses participants of the military parade in Moscow on November 7, 1941.

Yurovsky/SputnikHead of the NKVD Lavrentiy Beria was ordered to oversee the mining and destruction of factories, warehouses, institutions and critical infrastructure — including the Moscow Metro — which would be impossible to evacuate to the new capital in time.

The mining of elements of critical infrastructure in the capital sent a clear message to the anxious residents of Moscow: the Soviet leadership was preparing to abandon the capital and leave millions to the Nazis’ mercy.

Panic in Moscow

The rumors about the evacuation of the capital spread fast, despite the resolution’s secrecy. When the Metro failed to open for the first time in its history on the morning of October 16, 1941, as it was being prepared for total demolition, it spurred circulating rumors that the capital of the USSR might eventually fall into the hands of the Nazis. Soon enough, panic unfolded.

Many people abandoned their duties and property and rushed to railway stations hoping to leave the city before the enemy troops came. City-wide chaos ensued.

A witness of the events, Leo Larsky later described one episode of the hasty evacuation (link in Russian): “At three o’clock there was a traffic jam on the bridge. Instead of pushing the stuck trucks off the bridge and eliminating the traffic jam, everyone rushed to grab seats in them. Those who were sitting in the trucks desperately hit the attackers over their heads with their suitcases. The attackers climbed on top of each other, broke into the trucks and threw out the defenders like sacks of potatoes. But, as soon as the invaders sat down, as soon as the cars tried to move, the next wave rushed at them.”

Fear and panic ensued in the capital. Many workers showed up at their workplaces hoping for wage payments, but found that the management had left earlier. Angry and abandoned, some residents resorted to violence and looting.

“There are fights in the lines, old women are being strangled, young people are looting and policemen hang around on the sidewalks for two or four hours and smoke: ‘[We have ] no instructions,’” wrote Soviet journalist Nikolay Verzhbitsky about the panic in Moscow on that day.

Barricades on the streets of Moscow.

Arkady Shaikhet (CC BY-SA 3.0)It took radical measures to bring Moscow back to normal. On October 19, 1941 — after three days of chaos and panic in the capital — Stalin issued a decree that introduced the state of siege in Moscow that prohibited movement of cars and people without special permits at nighttime and gave the police permission to shoot “provocateurs” at sight.

Stalin’s personal decision to stay in besieged Moscow may also have contributed to calming the residents, as many took it as a sign that the Red Army would defend the city at all cost.

Thanks to the efforts of the Red Army, and those residents of the city who did not leave or resort to violence and panic, the Nazis failed to capture Moscow or destroy the Soviet armed forces up to the winter of 1941. Eventually, Nazi Germany faced a prospect of a protracted war with the USSR.

Click here for 5 facts about the most fearsome weapon of WWII.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox