What became of Grigory Rasputin’s descendants?

Grigory Rasputin - a favorite of the Romanov Dynasty, was a man with a very controversial reputation. After his murder in 1916, his image and role in Russian history became subject to a campaign of demonization. By 1933, the Rasputin name was all but erased, with nearly all of his descendants dying under similar circumstances. All of them, but one.

‘Malignant agents’

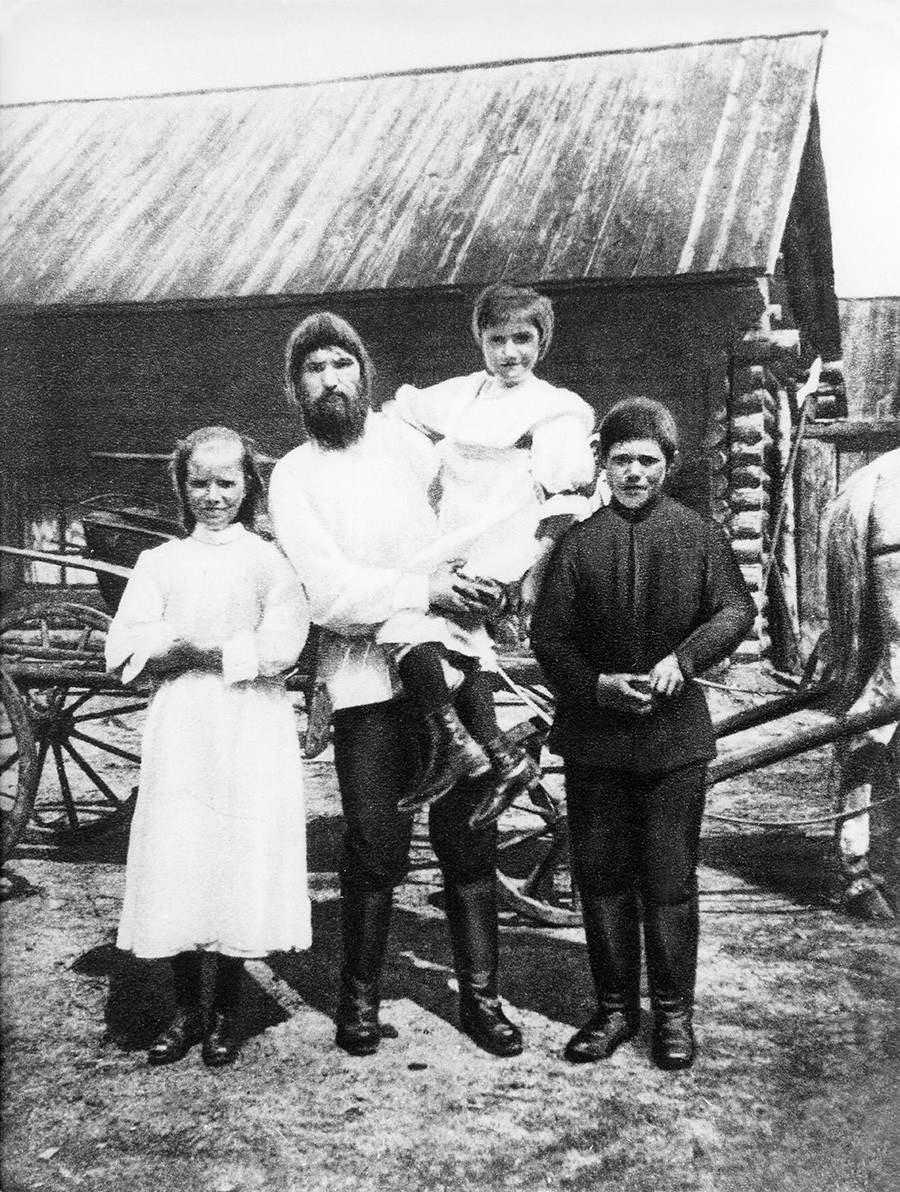

Of Grigory Rasputin’s seven children, only three survived to adulthood: Matrena, Varvara and Dmitry. They lived with their mother in the Pokrovskoye village, some 1,150 km from Moscow, until 1913. When Rasputin’s situation in the Royal court solidified, he decided to relocate to St. Petersburg permanently, along with his daughters, seeking to secure a future for them as upstanding ladies. Having enrolled Matrena and Varvara into a prep school staffed by the best teachers, he began to gradually introduce them to his new circle of friends - the royals.

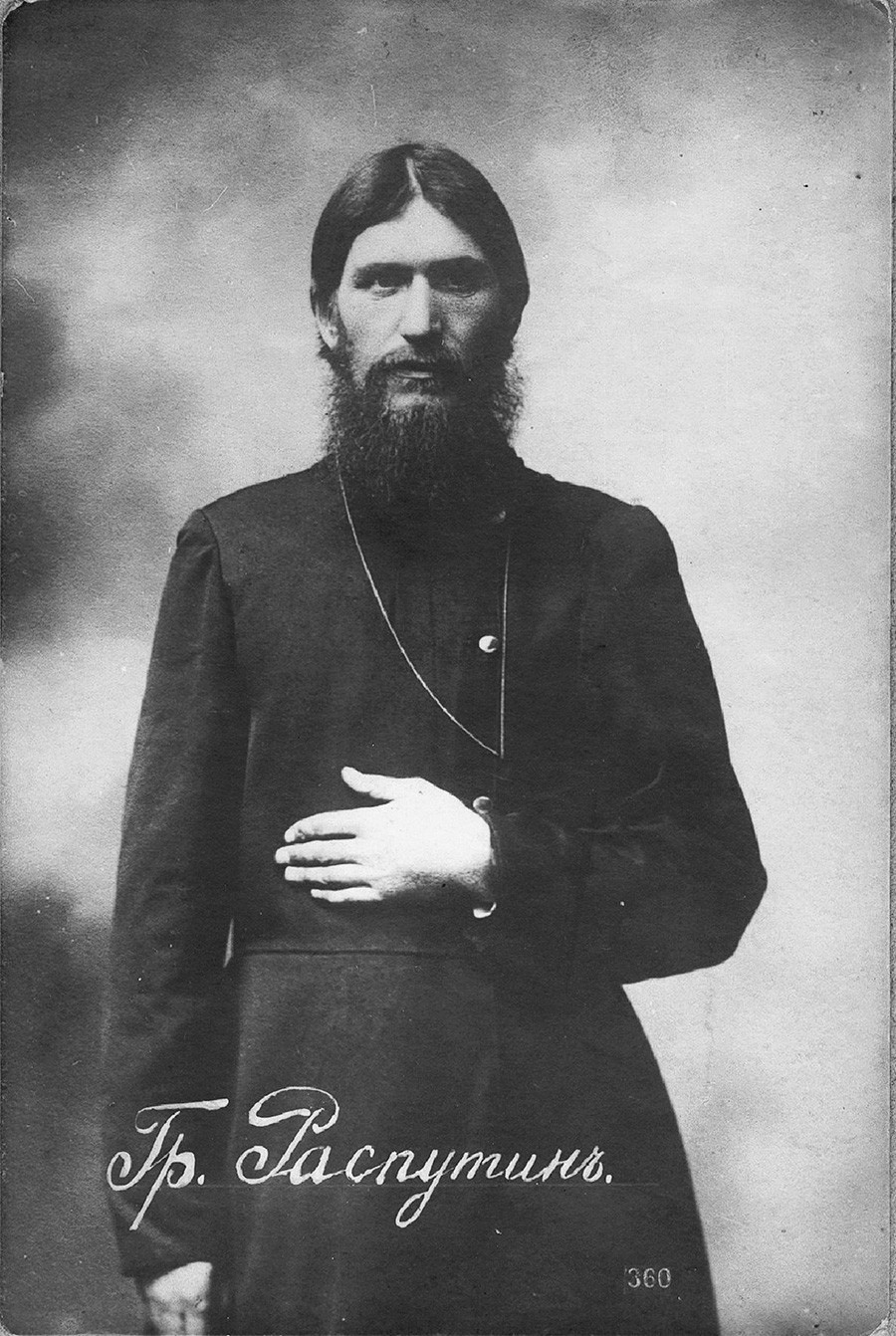

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (1869-1916)

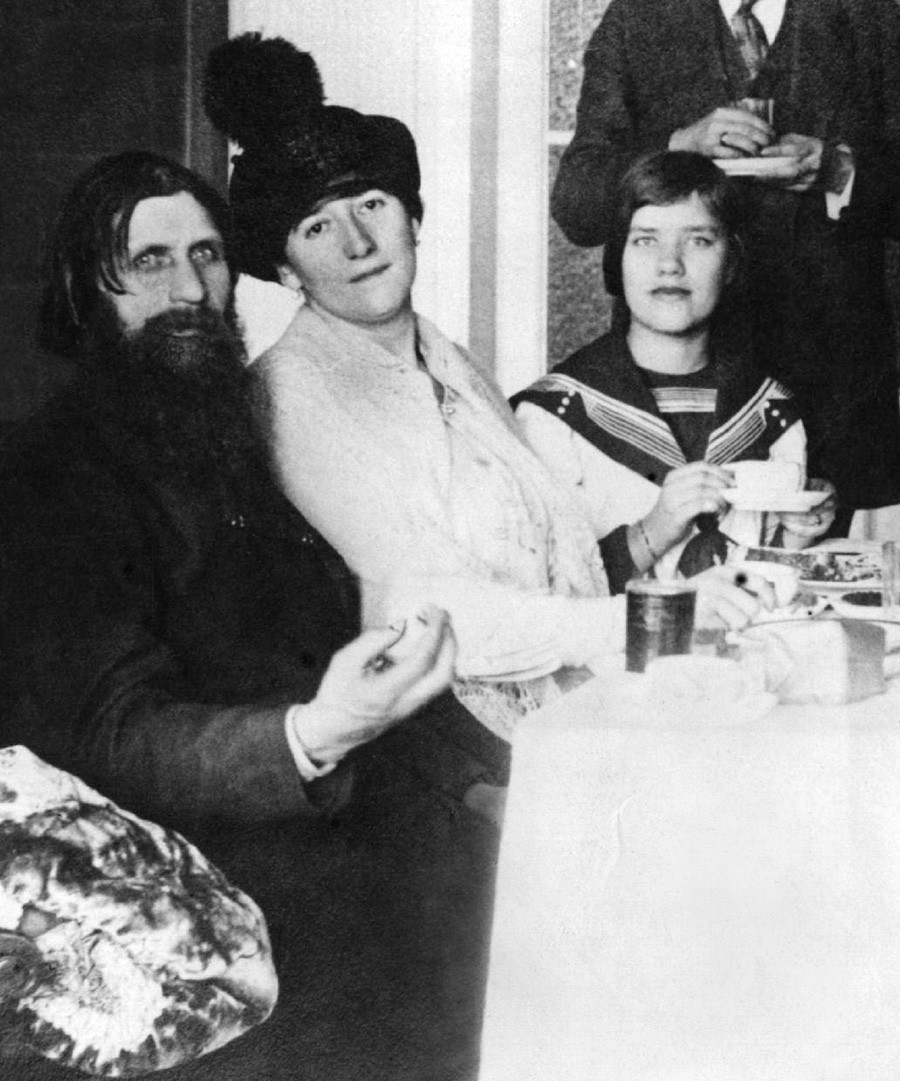

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty ImagesNicholas II’s children resembled something akin to delicate china dolls, Matrena would later recall in her memoirs: “The tsar’s children wanted to know everything about me: what gymnasium I study at, who does my hair and dresses me, if I have any mechanical toys, if I’ve seen their yacht yet, what our cow’s name was in Pokrovskoye and so on and so forth!” The girls quickly befriended the Romanov children. Matrena soon swapped her lower-class name for a softer-sounding Maria. However, anti-Rasputin sentiments began to grow after the family’s relocation to St. Petersburg a year later. They reached their peak after his death at the Yusupov palace. Rasputin’s family left town, but only Maria managed to leave the country.

Grigori Rasputin with his three children

ullstein bild/Getty ImagesNot long before, she married Boris Solovyev - an officer and loyal follower of her father’s and the royal family. She also acquired new identification papers and left for Europe via Vladivostok, as one couldn’t head westward because of the war. The trains on the Transsiberian often got stuck for months on end. The pair then left Vladivostok on a ferry, which was evacuating a portion of the Czechoslovakian corps. They had to get to Europe by way of Japan, Singapore and the Suez Canal. The journey took all of two years, with Maria delivering her firstborn. The family settled in Berlin, before relocating to Paris four years later. This escape saved Maria’s life - something that couldn’t be said for her brother and sister.

Grigori Rasputin with his wife and his daughter Matryona, far right, in 1911

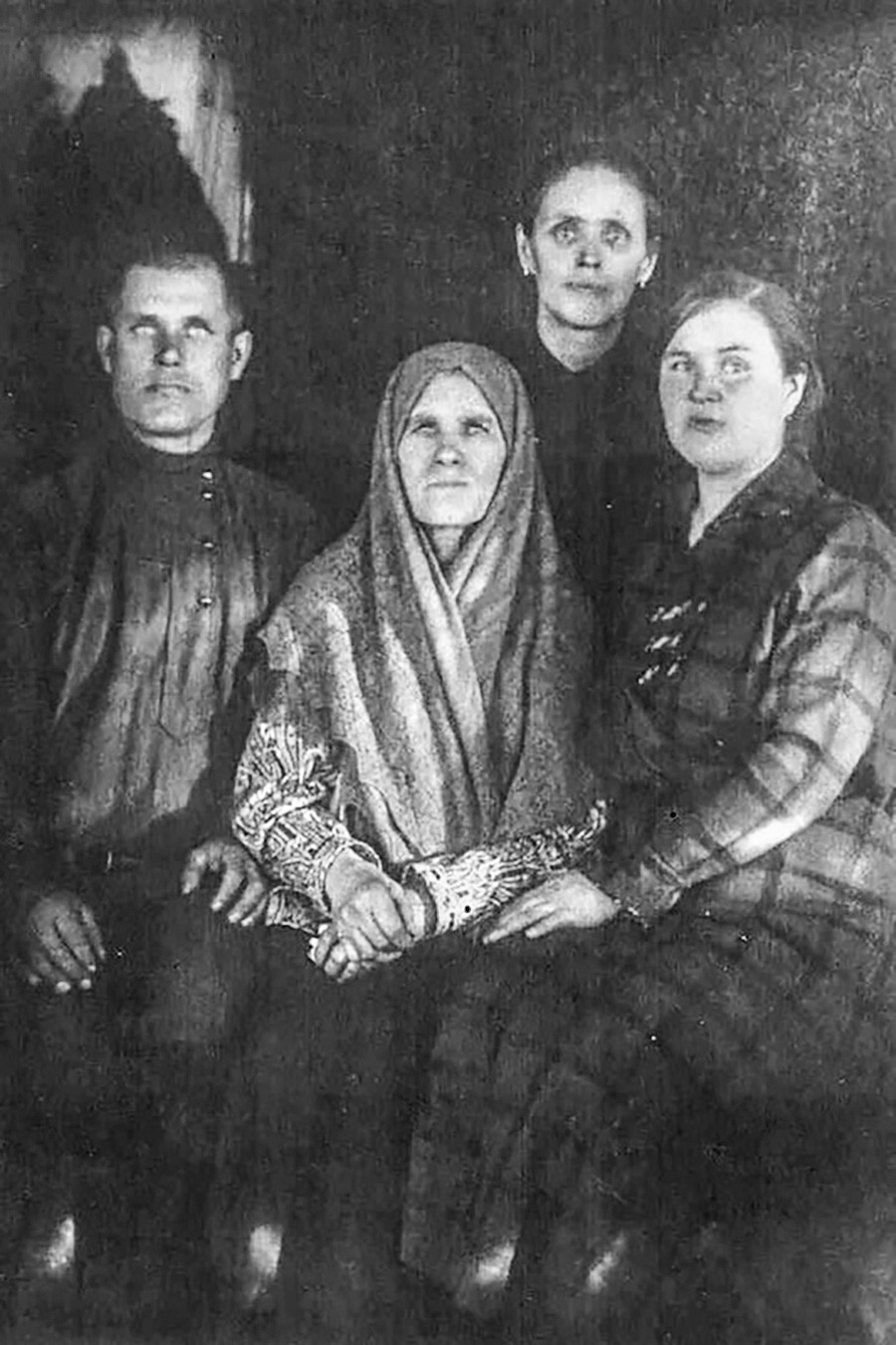

Public domainAfter her father’s murder, Varvara returned to Pokrovskoye to her brother. In 1922, they were stripiped of all rights and accused of being “malignant elements”. In the 1930s, Dmitry, his mother and family were arrested and sent to do labor in the North, where they died of dysentery. Meanwhile, Varvara simply disappeared. One theory claims that she died of typhus in the 1920s.

Daughter of a mad monk

Things weren’t going so well for the only surviving Rasputin daughter in Paris, either. Boris Solovyev opened a restaurant, but the business didn’t take off, with most customers being poor Russian emigrants dining there on open tabs. In 1924, he contracted tuberculosis and died soon after. By then, Maria had already had two children, Marie and Tatiana.

Having been left with nothing, she first worked as a housekeeper for rich families, before taking a job as a dancer at the Empire Theater (her ballet classes helped in that).

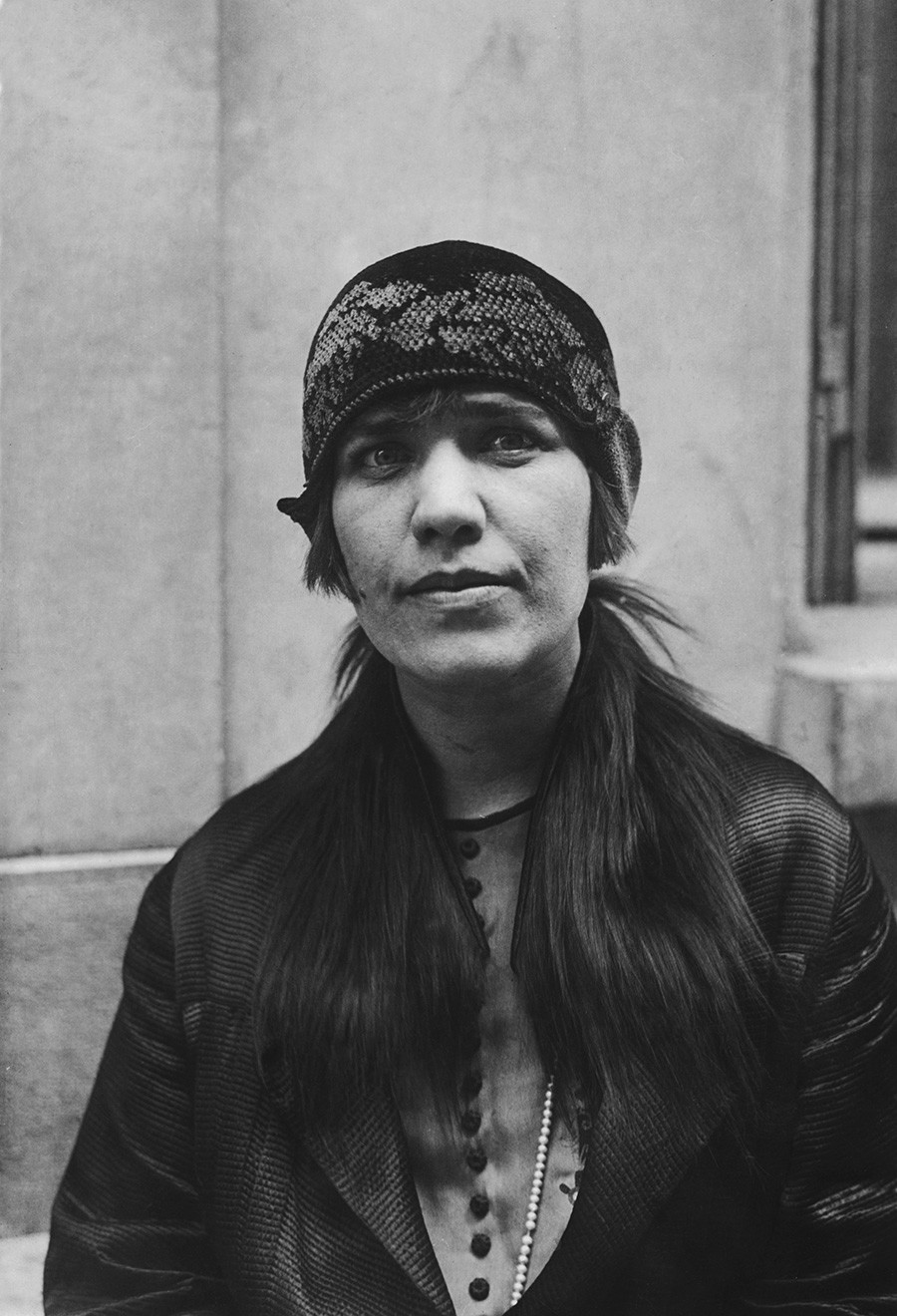

Maria Rasputin

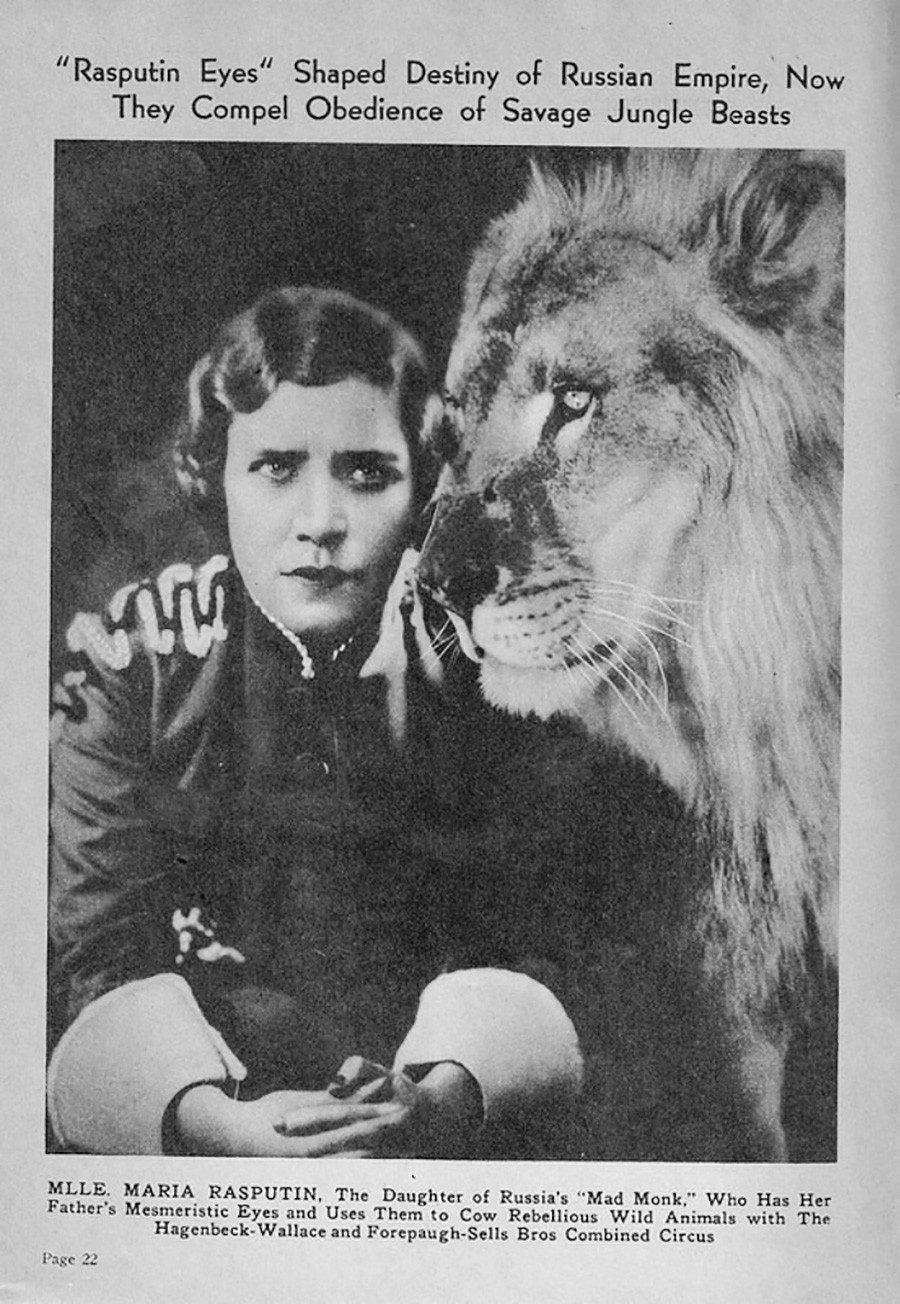

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesHer life would soon change, however. In the 1930s, the famous daughter of the Russian tsar’s favorite monk was spotted by the director of the ‘Barnun’ - an American circus. She got the job on the condition that she would perform in a cage with a lion. “Grandmother, of course, agreed,” her granddaughter (and daughter of Tatiana), Laurence Huot-Solovieff wrote. “Having fled the Revolution, as well as the First and the Civil Wars, a lion cage didn’t produce the same fear in her.”

Her famed surname played a significant role: the public showed great interest in seeing “Maria Rasputina, the daughter of the mad monk, made famous by his exploits in Russia” (as she was advertised on the posters), who, supposedly, had the ability to tame wild animals with nothing but her inherited “Rasputin gaze”. Maria toured almost all of Europe and the United States with that show.

It all came to an end in Miami: she was attacked by a polar bear. Having gone through a lengthy recovery at the hospital, she ended her career as animal tamer. Journalists would later sensationalize the story, writing that the fur of the bear that Rasputin collapsed on after being shot in 1916 was also that of a polar bear.

Maria then worked as a riveter at an American shipbuilding factory. After World War II, she transitioned to weapons factories, where she worked until old age, having received U.S. citizenship in 1945. She died in 1977 at almost 80 years old. Her surviving descendents reside in the West and her granddaughter Laurence Huot-Solovyeva occasionally visits Russia.

Forbidden topic

Laurence currently resides in a mansion in Paris, which has been outfitted with furniture she inherited from Maria Rasputin. Her bedroom contains photos of her great-grandfather.

For a long time, the Rasputin name was a forbidden topic in the family. “I remember father slamming his fist on the table and demanding that the name never be uttered at home and that the family’s Russian roots never be spoken of,” she told Kommersant daily. This ban on discussion was explained by the name’s dark reputation, which could have influenced the family’s life in Paris. “Here, Rasputin carries a negative connotation, as it is reserved for politicians with a strong penchant for giving advice.”

“Only with father’s passing, my cousin, his nephew, said: ‘We must remember our entire history, everything we know about great-granddad’,” although, even then, the conversation was kept strictly in the family.

Laurence told that story to her friends on the day of her 60th birthday: “Our guests nearly fell from their chairs from shock,” she laughed. Since then, the topic was no longer taboo and she now has a mission to spread the story so as to stop her great-grandfather’s name from being mythologized.

“If anyone thinks that I possess some unusual gifts, I must disappoint them,” Laurence says. “I’m simply a woman. Having been left alone, I worked as a secretary and raised children. I have three grandchildren. Over the past few years, my life has gained a new meaning spiritually… I’m more into Russian history, the history of Orthodox Christianity, I study my roots and spend time with Russian people.”

Laurence works with journalists, takes part in science conferences, but still confesses that some people try to avoid her. “I have friends that say: ‘You know, Laurence, I like you, but I cannot introduce you to my family.’ Simply because I’m Rasputin’s descendant.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox