How Soviet ‘sobering-up’ stations operated and what replaced them

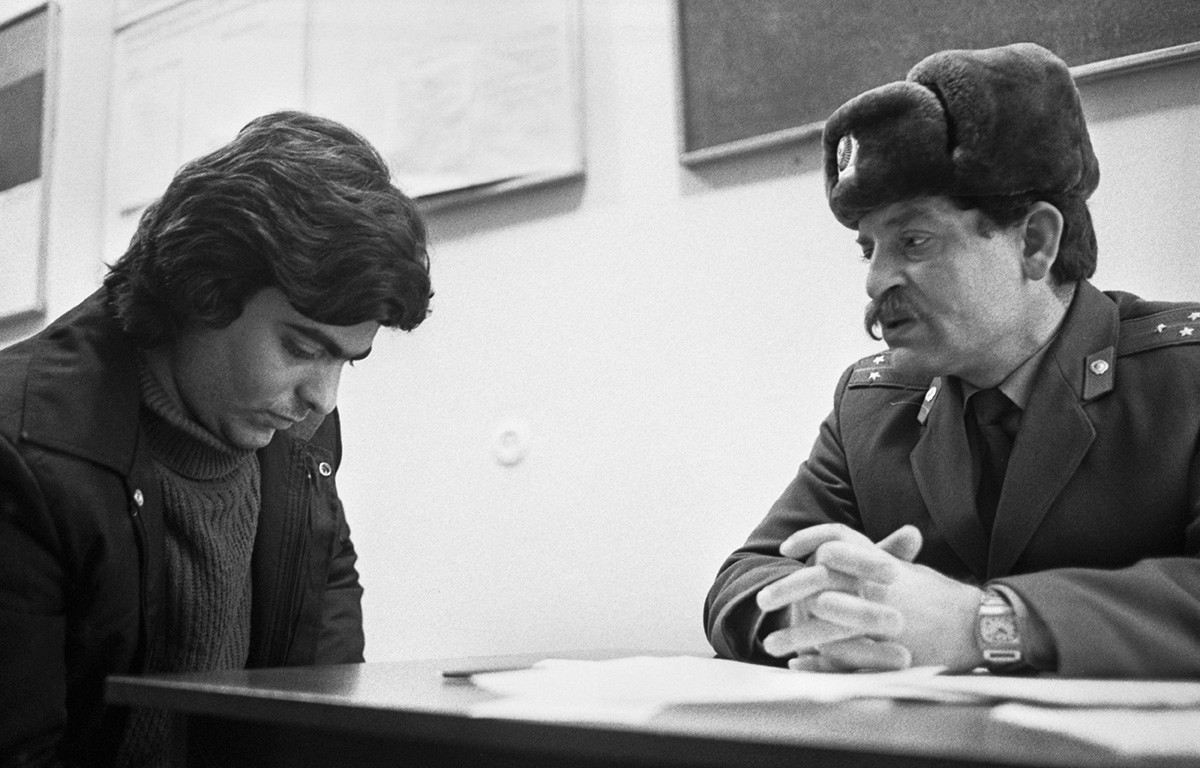

MOSCOW, RUSSIA. August 1, 1993. Detainees are taken to a detox centre

Alexander Shogin/TASSA narcologist, a plump middle-aged woman with a short haircut, is sitting at a long desk in an assembly hall. There is a microphone in front of her, into which she - in a monotonous voice – is describing the dangers of alcoholism to an audience of a several dozen unkempt men with wrinkled, drooping faces, who have not yet fully recovered from yet another hangover.

“I’ll start with somebody who has been here more than once. Here is Nikolai Ivanovich Gulepov. <...> Please stand up. This is your eighth time in a sobering-up station, eighth time! <...> We shall have to have a very serious conversation indeed! <...> You have had treatment with a narcologist and yet, you continue to drink,” she scolds a thin blond man in a coat and a checkered scarf.

USSR. The Moldavian SSR. Kishinev. December 31, 1987. Yevgeniya Fomovna Telipan, a paramedic at the medical detox center in Kishinev, at her workplace

Sergei Voronin/TASSThe man, like a child, is trying to explain himself, saying that he was indeed receiving treatment, did not drink for eight months, but then stopped the treatment and took to the bottle again. The doctor says that unless he resumes treatment, he will have to be subjected to involuntary treatment, but at that moment another patient takes the man’s side.

“Are you sure you are helping with this treatment? I had it and I want to say that it affects one’s genitals and liver!” the man in the audience challenges the doctor.

“It is vodka that has this effect!” the doctor counters.

This is what a typical preventive chat in a Soviet sobering-up station looked like. Back then, there were sobering-up stations in almost every city in the USSR and they lasted well into post-Soviet years, too. However, in 2011, sobering-up stations were abolished. How did they operate and is there a present-day equivalent?

First ‘shelters’ for drunkards

Sobering-up stations first appeared in the Russian Empire in the early 1900s. One of the very first ones opened in Tula, south of Moscow, and was called a ‘Shelter for the Intoxicated’.

The small brick building with several hospital beds inside was used to accommodate people who were too drunk to stand on their feet or fell asleep on the street in the cold. They were brought to the shelter by the police or a specially hired coachman, states the Diletant magazine.

Moldavian SSR. Kishinev. December 31, 1987. Police inspector, Senior Lieutenant Georgy Bottsa (right) talking to Leonid Boiangiu in a medical detox center in Kishinev

Sergei Voronin/TASSAt the shelter, new arrivals were fed, left to sleep it off, after which they were released. They were given brine, sometimes ammonia and on rare occasions “subcutaneous injections of strychnine and arsenic”. The only form of entertainment was a gramophone. Shelters like these accepted not only men, but women, too, sometimes even with children. For those cases, shelters had a children’s ward, where a child could wait for their parent “to recover”.

“In the first year after the shelter was opened, the number of people who died drunk in the streets of Tula dropped 1.7-fold. In 1909, there were 3,029 people treated at the shelter, including 87 as outpatients, with 60.72 percent of them ‘successfully cured’,” TASS News Agency reports.

By 1910, similar establishments began to open across the country; however, they lasted only until the 1917 revolution.

Cold baths and threats of dismissal in the USSR

Sobering-up stations were revived again in 1931. Drunk people were collected from the streets by police officers, but this time round the treatment they received was somewhat less delicate.

“We are struggling to lead a patient, he is resisting, swearing, starting to fight. The police officers and paramedic on duty, who are all experienced people, quickly manage to tame him: they knock him down on the floor, put a towel soaked in ammonia into his hat and press the hat to his face. A wild cry follows, but the man is half-subdued now. He is then handed over to two hulking women operating the dressing room. They knock him down on the sofa and strip him naked in less than a minute. The clothes are removed over his head from the back, with several ripped buttons rolling behind the sofa. The man is then dragged into a bath with lukewarm water, washed with soap and a washcloth, rubbed with a towel and, now meek, led into the dormitory. A naked man is always more humble than a dressed man, which cannot be said about women,” Alexander Dreitser, a doctor with the Narkomzdrav clinic, wrote in his book Notes of an Ambulance Doctor.

After this “cleansing”, the “patient” was examined by a doctor for possible injuries and then sent to sleep on a bunk bed. All of their belongings and money were recorded and put into a special bag. In the morning, they were returned to the owner. A stay in a sobering-up station was not free – it cost from 25 to 40 rubles (the average monthly salary in 1940 was 200-300 rubles) “depending on how violent” a patient was, Dreitser wrote. In exchange for the collected money, the offender was issued with a receipt for “medical care”.

However, a drunkard’s problems did not end there, since law enforcement agencies were required to report his or her stay at a sobering-up station to the person’s employer, after which the employee could be stripped of their bonus or even fired. Students who ended up in a sobering-up station risked expulsion from university. Many of those who found themselves in a sobering-up station wanted to avoid such serious consequences, so they offered bribes to the police not to report them.

If a person was taken to a sobering-up station three times in one year, they were sent to a narcological clinic for examination and treatment for alcoholism. They were also obliged to attend sessions conducted by employees of sobering-up stations and narcologists – to this end, there were special departments for the prevention of alcohol addiction.

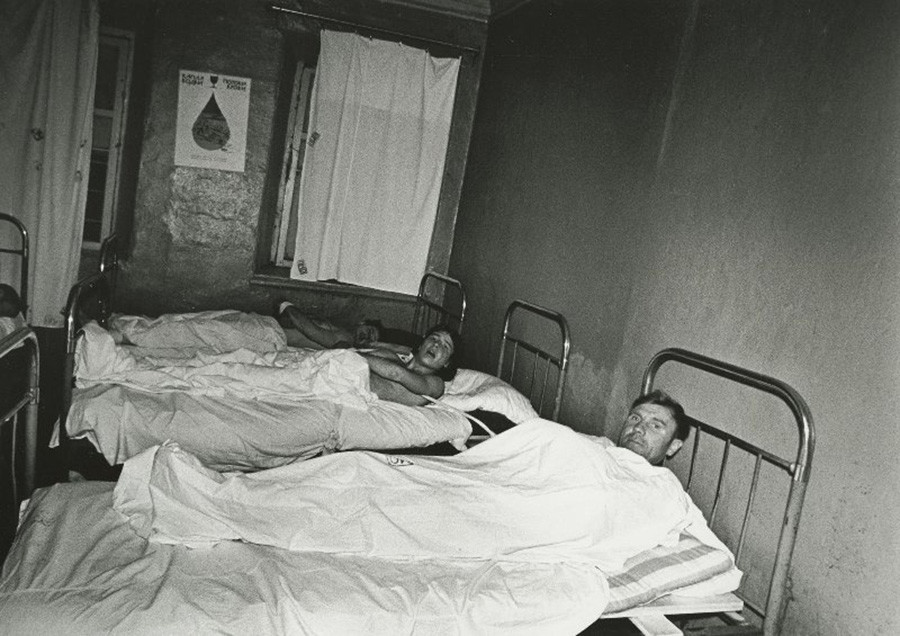

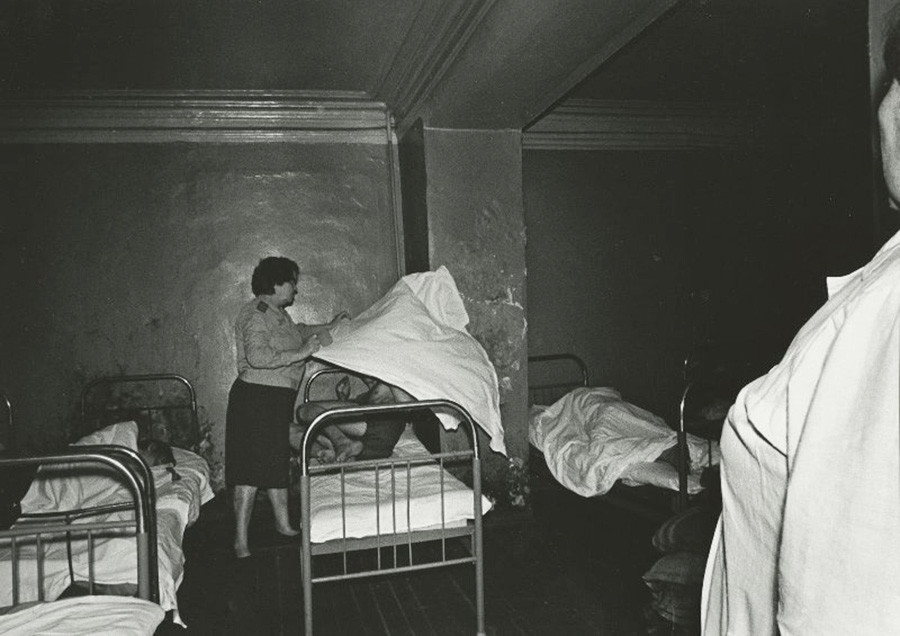

From the series "Vytyrevitel in Cherepovets"

Yury Rybchinsky/MMMM/FMDSobering-up stations did not admit pregnant women, minors, disabled people, military and police officers, as well as Heroes of the Soviet Union or Heroes of Socialist Labor – if found drunk, those categories of citizens were taken to their place of work, hospital or home.

However, none of those measures really worked: as Mikhail Gorbachev’s aide for international affairs Anatoly Chernyaev recalled, from 1950, alcohol consumption quadrupled and two-thirds of all crimes were committed in a state of intoxication. The main reason, according to Chernyaev, was an increase in the production of alcoholic beverages.

From the series "Vytyrevitel in Cherepovets"

Yury Rybchinsky/MMMM/FMDFrom May 30, 1985, under an order of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs, all drunken people whose appearance “insulted human dignity and public morality” were taken to sobering-up stations. They were mainly collected from the streets, parks, train stations, airports and other public places. Minors were taken in only in exceptional cases – when their identity and place of residence could not be established. Foreign diplomats could not be picked up either: if they were found drunk in the street, “a senior officer on duty had to report it to the duty officer for the district police department and follow the latter’s instructions”.

With the break-up of the USSR, the number of sobering-up stations began to drop gradually. In 2010, the then Russian president, Dmitry Medvedev, cancelled the 1985 order and, in 2011, all police-run sobering-up stations were shut down.

What happens now, or sobering-up stations 2.0

With the closure of sobering-up stations, people in a state of severe alcoholic intoxication or in an alcoholic coma were taken to ordinary hospitals. Another option was to involve private clinics, which can help a patient break a bout of heavy drinking with medicines and intravenous therapy. Their services start at 1,500 rubles (approx. $20) but can cost any amount, as there is no single price list at these clinics.

Courier Maxim (the name has been changed at his request) ordered the services of a private sobering-up station for his girlfriend Elena in September 2020. He says that one night, Lena went on a bar crawl with a friend and in one of the bars, she met a man, after which she – already drunk – followed the man to his place.

A patient at the medical detoxification center of the Khimki Department of Internal Affairs of the Moscow Region

Grigory Sysoyev/Sputnik“She disappeared for 24 hours and the following evening, a girl I had never met brought her to my place and said that Lena had been having not only alcohol, but also drugs. Her lips were blue and she did not respond to anything, so I called a sobering-up team. Two doctors came, took her electrocardiogram and put her on an IV. They were trying to get me to send her for treatment to their private clinic, which would have cost 140,000 rubles (approx. $1,800). I didn’t have that kind of money, so I ended up paying 15,000 rubles (approx. $194) for the visit and that was it,” Maxim recalls.

According to him, Elena woke up a few hours later, could not remember anything and went to work as if nothing had happened.

In some Russian cities - for example, Chelyabinsk, St. Petersburg and Nizhny Novgorod – the local authorities have decided to restore sobering-up facilities, with the money for it allocated from the regional budget. They accept only people in a moderate state of intoxication, who are examined by doctors and - if there is no need for urgent medical assistance - are left to sleep their condition off at the facility.

A patient at the medical detoxification center of the Khimki Department of Internal Affairs of the Moscow Region

Grigory Sysoyev/SputnikStarting from January 1, 2021, a law has come into effect in Russia reviving the use of sobering-up stations. Police officers will take all people found in public places in a state of alcoholic or drug intoxication, who are unable to move or orient themselves, there. Sobering-up stations will also accept drunkards from their homes, but only if people living with them report them and if the police decide that the person in a state of alcoholic or drug intoxication can harm the life and health of others or damage property.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox