Why did British troops attack Russia in 1918?

Major General Frederick C. Poole in Arkhangelsk.

Public DomainThe intervention of the Entente Powers in Russia at the end of WWI had nothing to do with fear and hatred of communism (although such sentiments certainly existed). The main reason was the policy of the Bolsheviks, who had just swept to power and were determined to pull Russia out of the war against the Central Powers.

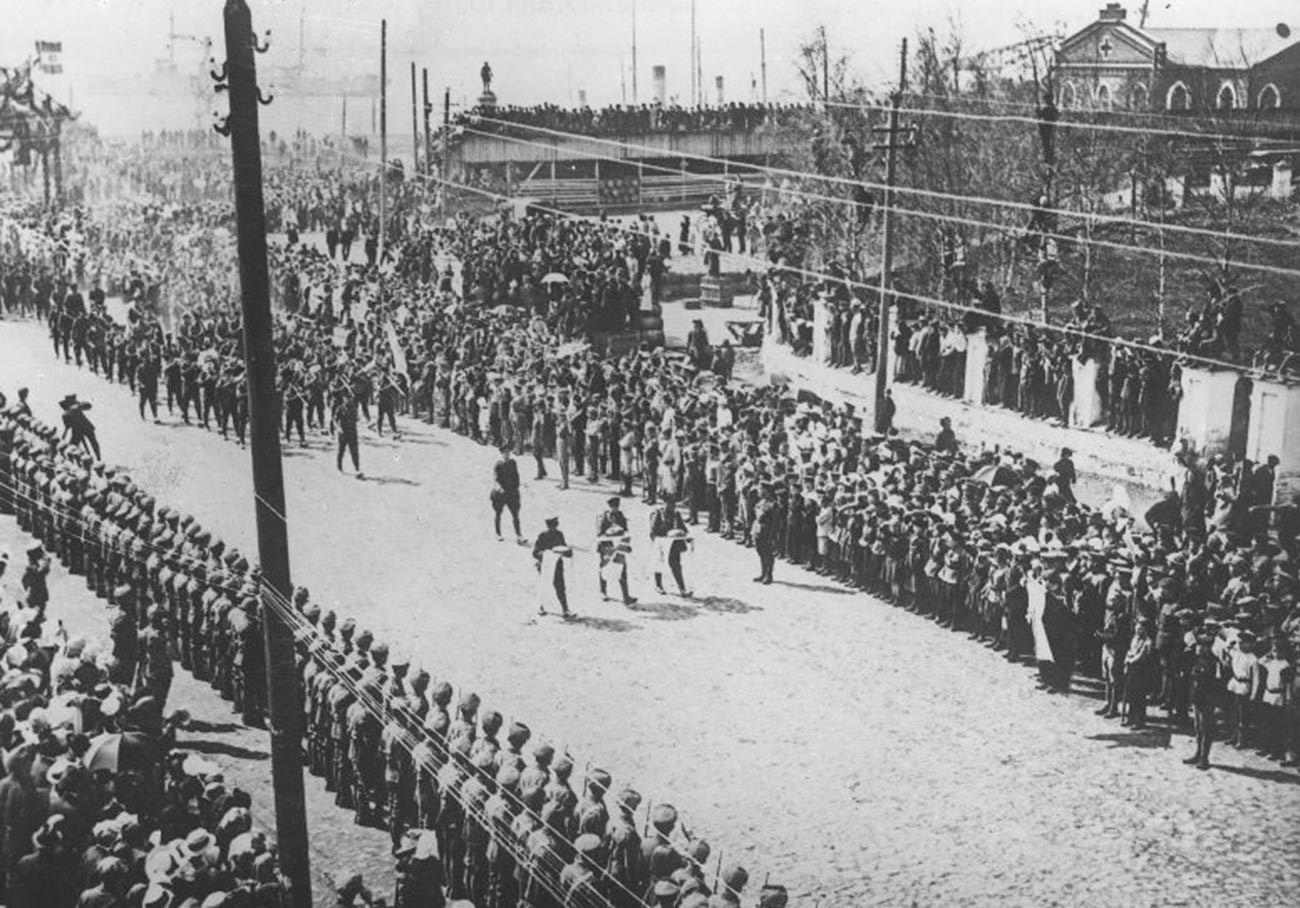

Polish, British and French officers inspecting a detachment of Polish troops of so called Murmansk Battalion before their departure for the front, Archangel 1919.

Public DomainLondon and Paris were horrified at the prospect of a truce between Soviet Russia and Germany that would free up hundreds of thousands of the Kaiser's soldiers for deployment to the Western Front. The best way to prevent such a scenario, they believed, was by supporting the so-called White forces, which emerged in opposition to Bolshevik power in the nascent civil conflict. Most of the leaders of the White movement were keen to fight the Germans till the bitter, yet victorious end, which suited the British and French to a tee.

Anton Denikin, commander-in-chief of the ASFR, and british Major General Frederick C. Poole.

Public DomainOn Dec. 23, 1917, Britain and France signed an agreement on joint intervention in Soviet Russia and its division into spheres of influence. The first British soldiers landed in Russia’s northern ports in the spring of 1918, immediately after the conclusion of a peace treaty between the Germans and the Bolsheviks at Brest-Litovsk on March 3. The troops of His Majesty George V also made incursions into the south of the country, in the Transcaucasus, in Central Asia and in the Far East. “I imagined the brilliant entry into the Russian capital, where great princesses will be saved from revolution,” a British major later wrote.

British troops in Arkhangelsk.

МАММ/MDF/russiainphoto.ru/The British leaders, however, had no plans for a full-scale involvement in what became the Russian Civil War. They intended to support their White allies, but with as little bloodshed as possible on their part. The ambiguity of the mission gave rise to misunderstanding among the troops. Bob Vincent of the Royal Yorkshire Regiment, who served for a whole year in the south of the country, recalled that he “never really met any Russians at all or had any idea why [he] was there.”

British troops in Odessa.

Public DomainThe interventionists were primarily engaged in organizing and training anti-Bolshevik formations. In the north, for instance, they helped to create the Karelian, Slavo-British Allied and Murmansk legions, the last of which consisted of captured Red Army soldiers. Down in southern Russia, British officers provided artillery and tank training. Britons also served on the staff of the "Supreme Ruler of Russia", Admiral Kolchak, in Siberia.

Officers of the Slavo-British legion.

Public DomainA great asset for the White armies was the supply of weapons and ammunition from London. The Armed Forces of Southern Russia (AFSR) under General Anton Denikin alone received enough equipment for almost half a million soldiers (although his troops did not exceed 300,000), as well as 1,200 artillery pieces, 6,100 machine guns, 200,000 rifles, 74 tanks and more besides.

The remains of an armoured train, Murmansk, September 1919.

Public DomainNevertheless, the British interventionists and the Red Army did clash periodically. On Oct. 9, 1918, the former captured Dushak station in modern-day Turkmenistan, dislodging the Soviet garrison. For four days in November of that same year, British, Canadian and American troops successfully defended themselves at the village of Tulgas in northern Russia against the Reds, losing more than 30 men in the process. Then, in the summer of 1919, British tank crews and pilots took part in the storming of Tsaritsyn (Stalingrad).

A British Mark V tank.

Public DomainBy late 1918, the original objectives of the intervention had grown irrelevant. London's fears about a Soviet-German peace and the transfer of the Kaiser’s troops to the West had not materialized – the Germans were too bogged down in the ruins of the former Russian Empire and could not seize the opportunity that presented itself. The conclusion of the Armistice at Le Francport near Compiègne on Nov. 11, 1918, which meant Germany’s unconditional surrender, raised questions over the utility of British soldiers fighting and dying in cold, far-flung Russia. “[It is] simply scandalous... to be fighting now and under such conditions when there is peace on other fronts,” wrote one British military engineer.

British officers in Siberia.

МАММ/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThe sole purpose of continuing the intervention now appeared to be the fight against Bolshevism, which led to growing discontent in British society. In January 1919 British socialists launched a large-scale campaign under the banner “Hands Off Russia!” At the same time, a heading in the newspaper The Daily Express thundered: “The frozen plains of eastern Europe are not worth the bones of a single grenadier.”

British troops in Siberia.

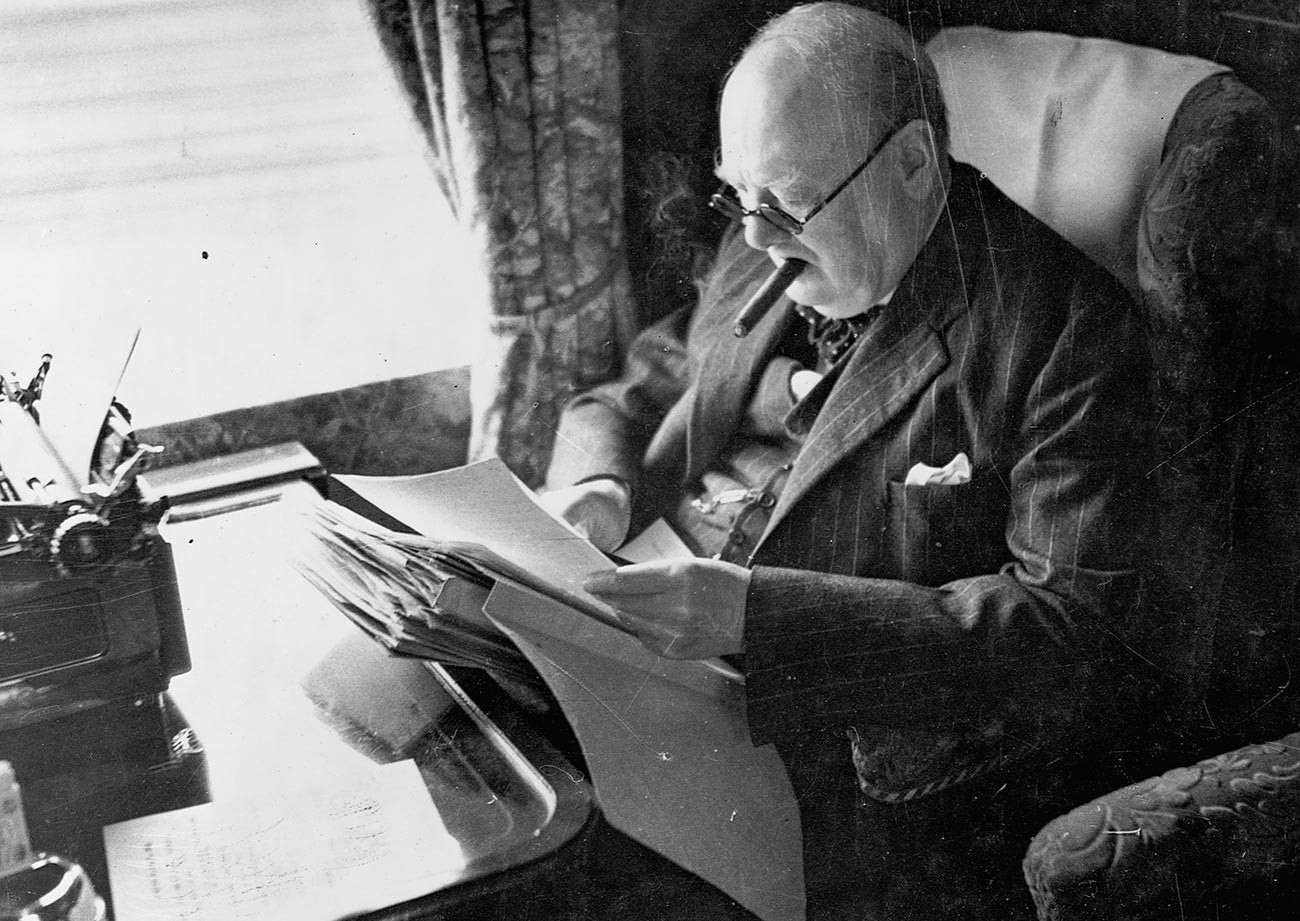

МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruThe main advocate inside the British government for continuing the intervention was the ardent anti-communist war minister, Winston Churchill, who declared Bolshevism to be “not a political thought but a disease.” The press openly described Britain’s involvement in Russian affairs as “Mr Churchill’s private war,” but even he was powerless when, in the fall of 1919, the AFSR was defeated at Moscow and White hopes of victory in the Civil War melted away like a snowflake.

Winston Churchill.

Library of Congress/Corbis/Getty ImagesThe British troops, like those of the other Entente Powers, were gradually withdrawn from Russia. Although London officially recognized the USSR only in 1924, back in November 1920 Prime Minister David Lloyd George had begun secret talks with the Soviet government with a view to resuming trade relations, knowing who the de facto rulers of the country really were.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox