These athletes fled the USSR. How did they do it?

Viktor Korchnoi: He planned his escape for years and left his family behind

Defected in July 1976 during a chess tournament in Amsterdam.

Viktor Korchnoi

Fred Greenberg/SputnikChess grandmaster Viktor Korchnoi never called himself a dissident or opponent of the system and regarded his defection as a “career-saving” move. Although a four-time USSR champion, he nevertheless repeatedly said in interviews with the Western media that he didn't have equal opportunities in his own country and this ran counter to the principles of fair competition.

He believed that the Soviet authorities chose their own favorites and provided them with support of all kinds. “The authorities chose [Anatoly] Karpov as their favorite, because he fitted the image of champion perfectly: He is [ethnically] Russian, comes from the provinces, he is young and exceptionally loyal to the regime. During a match, Karpov would enjoy unprecedented support, was surrounded by first-class grandmasters and was praised in the press,” was how Korchnoi recalled Anatoly Karpov, one of his main rivals.

For this criticism, Korchnoi once had his stipend reduced and was banned from leaving the USSR. A year later, however, the ban was lifted (incidentally, after Karpov vouched for him). In 1974, he decided to emigrate, but didn’t tell anyone - not even his own wife and son. While on foreign trips to chess tournaments, he gradually transferred important documents, photographs and books to Western Europe. In 1976, at a tournament in Amsterdam, he gave yet another strongly-worded interview and realized that this time he wouldn’t get away with it. The following morning, he went to the nearest police station and asked for political asylum.

Viktor Korchnoi

Mikhail Medvedev/TASSKorchnoi was not granted asylum, but only a residence permit. So, to get refugee status he travelled to Switzerland and, this time, he succeeded. In the Soviet Union, his family subsequently had to live through many deprivations and difficulties, something that Korchnoi had been aware of before he had fled. “It could have been easily predicted that my son would find himself in a sorry situation. But experienced people told me that, when you take a decision like this, your conscience should not be part of it,” he said.

His son Igor was expelled from university and drafted into the army to ensure that under no circumstances could he be allowed to travel abroad as someone having access to “military secrets”. Realizing this, Igor ignored the conscription summons and, as a result, was convicted and served two years in a prison camp in the Urals. Korchnoi’s wife Bella couldn’t even easily sell their car: It was registered in her husband’s name and power of attorney documents he sent her from Switzerland kept getting “lost” in transit. Korchnoi personally asked Leonid Brezhnev to let his family leave the country and appealed to U.S. President Jimmy Carter and even the Pope. The authorities relented only in 1982, granting the family permission to leave.

Ludmila Belousova and Oleg Protopopov: They hid in Swiss hotels

Defected in September 1979, while on tour in Switzerland.

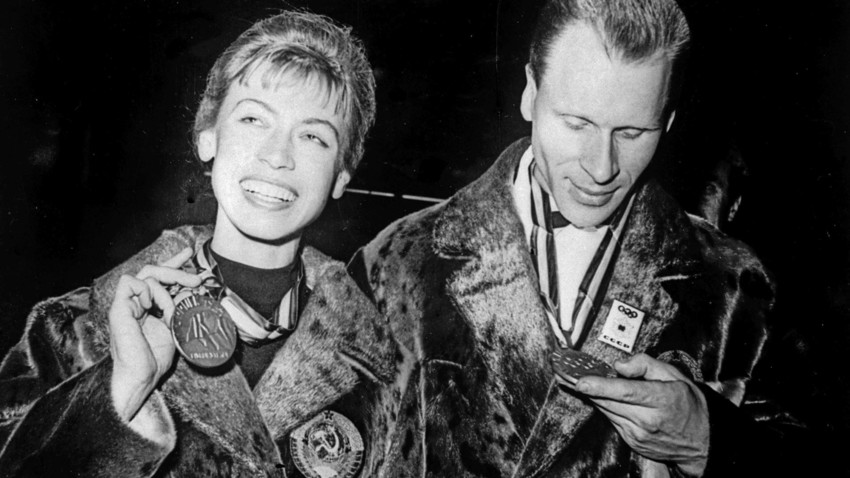

Ludmila Belousova and Oleg Protopopov

SputnikIn 1964, the celebrated married couple won the first-ever gold for Soviet figure skating at the Innsbruck Winter Olympics and then repeated their success at the next Winter Olympics in Grenoble, France. Between the two Olympics, they managed to win every available title at world and European championship level. The news of their defection stunned even the West, because the couple were members of the Communist Party, were regarded as “exemplary patriots” at home, enjoyed much attention and public affection and had a two-bedroom apartment.

Belousova and Protopopov approached the Swiss police in the town of Zug, not far from Zurich, while on tour with the Leningrad State Ballet on Ice. According to the couple, they had their Soviet passports confiscated straight away and then were moved from one hotel to another. Even the fugitives themselves didn’t know their exact whereabouts until they were granted asylum.

Ludmila Belousova and Oleg Protopopov

Dmitry Donskoy/SputnikThey took this desperate step after the Ministry of Sport switched its focus from the 1970s onwards to up-and-coming young skaters, while the figure skating legends were demoted to the category of mature and, thus, less promising athletes. The skaters complained that they were effectively being pensioned off or diverted to training duties, while they were still ready and willing to perform. Oleg Protopopov also saw another reason why their career was “crudely cut short”: “They were afraid that if we won our third Olympic Games, we would remain abroad. A low blow below the belt.” The financial arrangements did not suit the couple either: As they toured the whole world, almost all the fees they earned went to their tour organizers Goskontsert, the Soviet state concert booking organization. Of 10,000 dollars received for a show in New York, the skaters ended up with just 53 dollars.

The couple waited 16 years for their Swiss passports and received them only after the collapse of the USSR, in 1995. When they were both already over 60 they wanted to represent Switzerland at the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano but - quite predictably - they failed to qualify.

Alexander Mogilny: He defected because he was poverty stricken

His defection occured in May 1989 at the World Championships in Sweden.

Alexander Mogilny

Fred Greenberg/SputnikThe Olympic ice hockey champion and world champion was just 20 when he rang representatives of New York’s Buffalo Sabres and asked to be brought out of Sweden where the Soviet team had just won the World Championships. They made a dash to Sweden on the first available flight and the following day took the “best 20-year-old player in the world” with them to America.

Initially, Mogilny said his decision had been motivated by state policy in sport: “I saw what the attitude here was to older colleagues and realized what would happen to me when I got to the same age. At the end of their careers, they were left with nothing. This didn’t suit me.” He later said that, at home, he was very poor. “I was genuinely poverty stricken! I was Olympic champion, world champion and three-time USSR champion. And, at the same time, I didn’t even have a square meter of housing to my name. Who wants such a life?”

Alexander Mogilny

Igor Utkin/TASSThe Soviet side blamed everything on commonplace greed on Mogilny’s part. After fleeing to the USA, he signed a 630,000-dollar contract, bought himself a house and a Rolls-Royce and lived like a superstar. In the NHL, he was given the nickname ‘Alexander the Great’ and was the highest-scoring forward in the 1992/1993 season and the first Russian ice-hockey player to become a captain in the NHL league.

Sergei Nemtsanov: He made a failed bid to flee because of a girl

He defected in July 1976 during the Montreal Olympics.

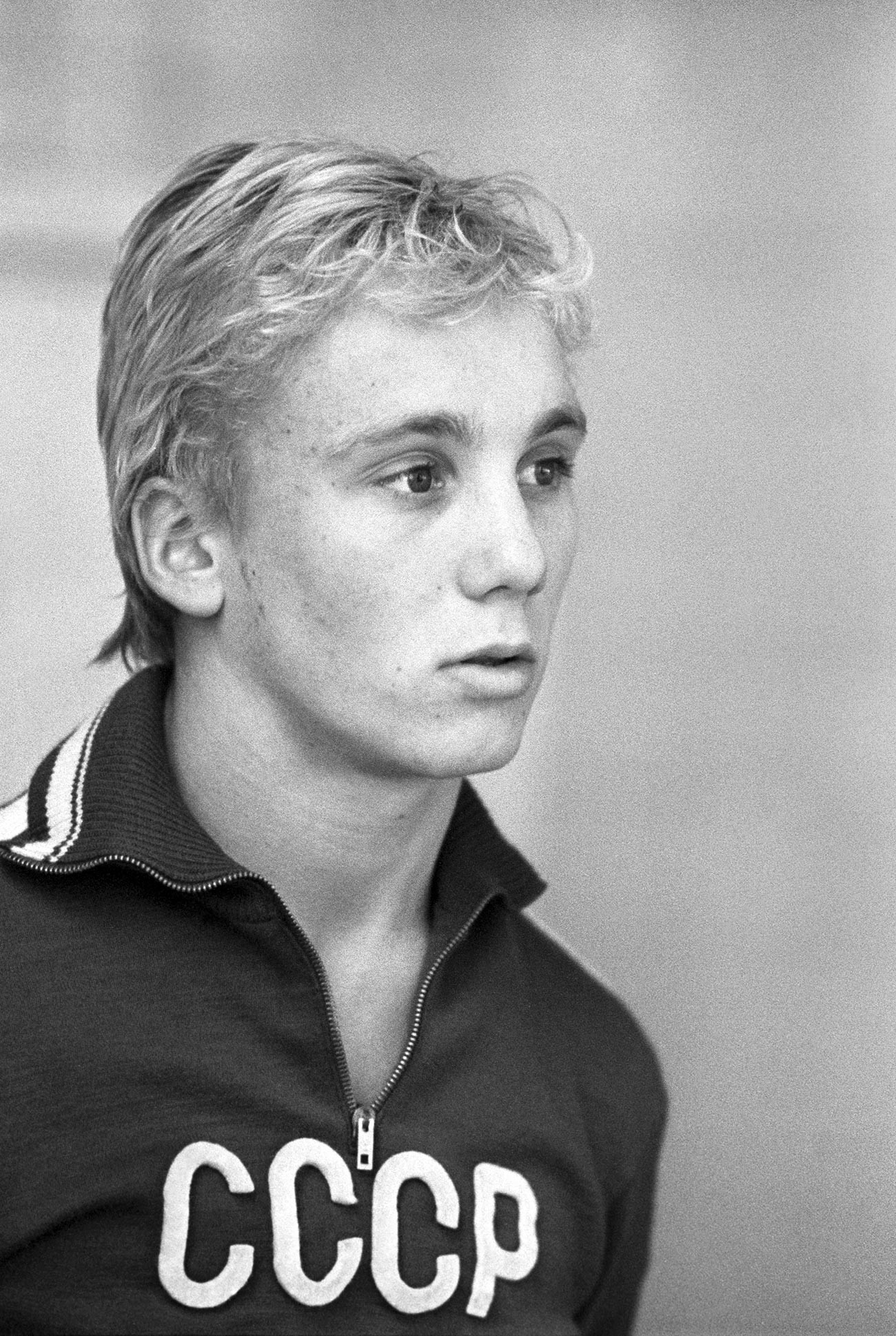

Sergei Nemtsanov

V.Kutyrov/TASSNot all Soviet defectors had clear motives. There was the notorious 1976 case of 17-year-old Soviet diving champion Sergei Nemtsanov. While taking part in the Montreal Olympics, he applied for asylum to the Canadian Immigration Office in the Olympic Village.

According to the Soviet version of events, the athlete had performed poorly at the Games and had failed to be selected for the national team set to take part in an upcoming competition in the USA. Upset over this, he had allegedly fallen victim to Western propaganda and had been lured by an offer to remain. The Soviet Union even accused Canada and the U.S. of “brainwashing” and kidnap. After a meeting with Nemtsanov under the watchful eye of Canadian lawyers, the Soviet side claimed he had appeared pale and, with glazed eyes, kept repeating the phrase “I chose freedom” like a robot. It might be added that four Romanian athletes also defected during the same Games, but everyone’s attention was exclusively fixed on the “golden-haired Russian Apollo”.

The Western press published rumors of a different kind: that Nemtsanov had fallen in love with diver Carol Lindner from the U.S. team and that was why he had decided to defect.

The trouble, however, was that he was underage and, thus, unable to apply for political asylum. Realizing that there was still time, the Soviet Union mounted a “Sergei come home” campaign and set about persuading him to return. One of the levers they applied against him was an audio recording of a message from Nemtsanov’s grandmother, who had brought him up: She begged her grandson to come back and not to leave her on her own. This had the desired effect and Sergei decided to go back. The Canadians let him go on one condition - that no punitive measures were taken against him.

The condition was met, but Nemtsanov’s career was at an end. He was no longer allowed to travel abroad and fellow Russians started regarding him as a “traitor”.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox