Why did 500 Africans protest on the Red Square in 1963?

On a cold December day in 1963, black students from African countries occupied the Red Square in the first major protest in Moscow since the 1920s. The death of a medical student from Ghana, which was said to have triggered the protests, was shrouded in mystery. In the days leading to the protests, the Soviet authorities noticed suspicious patterns and suspected foul play.

The mysterious death in Khovrino

On December 13, 1963, a body was discovered in a stretch of wasteland along a country road in Khovrino, one of Moscow’s northern districts. The victim was a black male. The police quickly discovered the identity of the deceased: Assare-Addo, a 29-year-old medical student from Ghana. The victim had a small wound under his chin. To further perplex the investigators, the body was discovered in the location far too remote for Assare-Addo to wander in accidentally, as he lived in a different city altogether. The news quickly spread within the community of black African students studying in the USSR.

Being a major ally of Marxist anti-colonial movements across the African continent during the Cold War, the Soviet Union provided the youth from some African countries with scholarships to study in the USSR. In 1960, the Soviet government even established a new university named after the Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba to provide education for people from socialist countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. With an influx of black students into Soviet society, isolated incidents of racial conflicts were bound to happen, but those had never led to murder before.

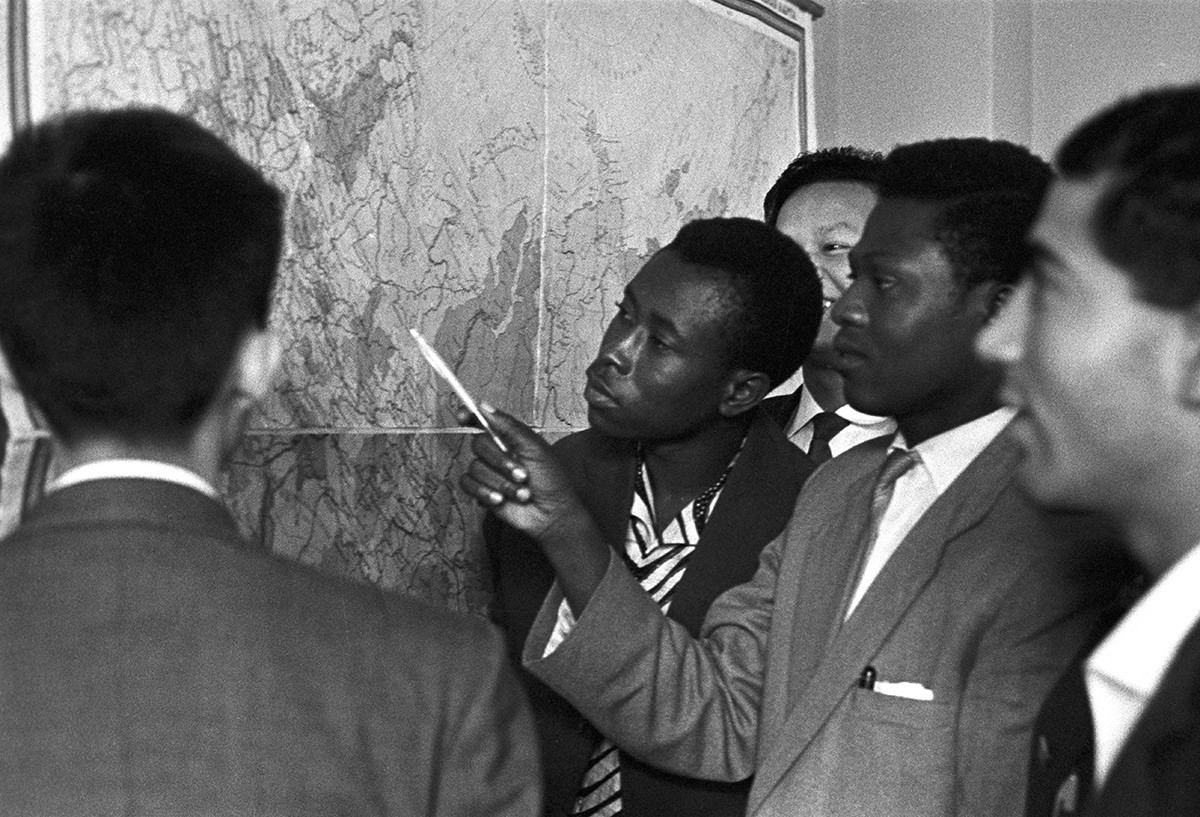

Inside the new university in Moscow named after the Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba.

Vladimir Minkevich/SputnikSome students leaked a story about Assare-Addo’s wedding to a Russian girl that was allegedly scheduled to happen on Saturday, the day after his body was discovered in Moscow. One of the theories the black protesters put forward was that their Ghanian fellow was killed by the girl’s relatives to prevent the marriage they did not approve of. Another theory claimed Assare-Addo fell victim to a random racially motivated attack. The perceived injustice towards black Africans in the Soviet Union sparked protests which spilled onto the Red Square.

‘A second Alabama’

Soon after the news about the discovery of the body spread among the African students in Moscow, black protestors hit the streets. Gathering at the Ghanian embassy in Moscow, the crowd of approximately 500 people moved to the heart of the Soviet Union, the Red Square.

The protestors, almost entirely male, carried placards with catchy dramatic slogans, like “Moscow, a second Alabama”, “Stop killing Africans” and “It’s the same thing all over the world”. The Soviet police made a half-hearted attempt to block the procession, but were unable to prevent it from accessing the Red Square. No arrests were made, perhaps out of political considerations. Once there, the protestors gathered at the Spasskiye Gates of the Kremlin, where they gave interviews to Western news correspondents.

Hoping to dispel the angry crowd and take the situation under control, the Soviet authorities opted for negotiations. Soviet Minister of Education Vyacheslav Eliutin invited a few representatives of the African students inside for talks.

Eliutin handled the delicate situation skilfully like an experienced politician. The minister expressed sympathy over the death of Assare-Addo and proposed a minute of silence in his honor which temporarily placated the belligerent protestors.

Then, Eliutin proceeded with a speech:

“We have a large country and it is possible to find isolated individuals who are bad people, just as in any country, there is a small number of people prepared to commit hooligan acts. These isolated individuals can, of course, cause offense to a Soviet citizen or a foreign citizen. But it is impermissible and incorrect to generalize or draw conclusions based on such instances, if they should take place, or to talk about the relations of the Soviet people towards you on this basis. This is something that every unprejudiced, objective person should understand. It has also never happened and none of you can say that it did, that one of our deans, teachers, or ministry officials has let slip a bad word or deed in relation to you.”

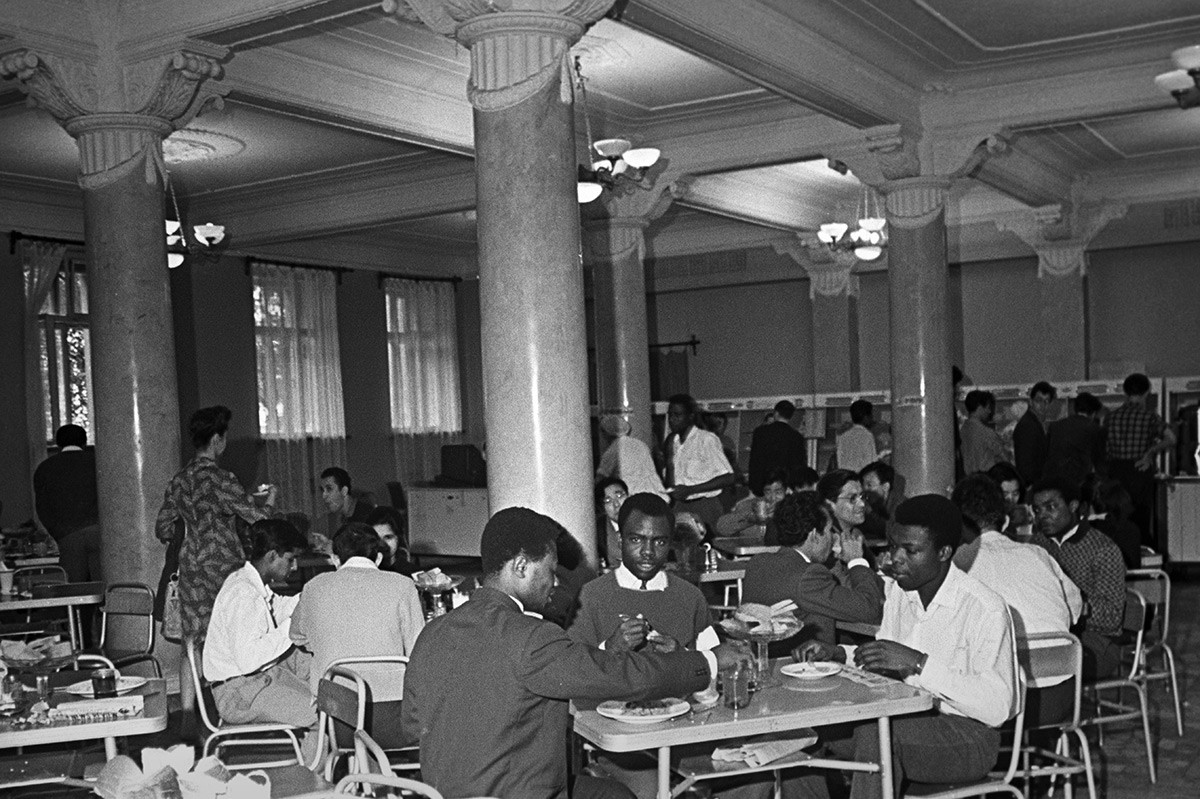

Students of the university in Moscow named after the Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba.

Eugene Tikhanov/SputnikThe line the Soviet authorities took regarding the protests was equally cunning and masterful: they placated the initial outrage, promised a thorough investigation into the death of the medical student, denounced the protests — which they thought played into the hands of imperialists and put the Soviet Union in a bad light — using the universities’ newspapers and a wider academic community and ruthlessly dealt with the most active instigators.

Ulterior motives

The autopsy conducted by a Soviet doctor working under the observation of two advanced medical students from Ghana, who were invited to attend the procedure for the sake of transparency, showed no sign of violent death. Instead, it was ruled that the death was “an effect of cold in a state of alcohol-induced stupor”. Assare-Addo did not fall victim to a hate crime; instead, it was an unfortunate accident and, perhaps, carelessness that had killed him.

Students at the Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow.

Vladimir Minkevich/SputnikAlthough not everyone was happy with the official coroner’s report, the Soviet authorities moved swiftly to close the case and address another, more politically troubling mystery: how were the African students able to mobilize so quickly for the protest?

The Soviet authorities were perplexed by a few details surrounding the protests. The body was discovered on December 13 and the protest was held on December 18. However, the Ministry of Education had reportedly been notified by universities from Leningrad and Kalinin that Ghanian students from these cities were summoned to Moscow to attend an event at the Ghanian Embassy as early as December 9. When inquired about the event, the Ghanian Embassy said it did not summon the students and it did not have any event planned for the dates.

Curiously, the authorities concluded that Assare-Addo — who studied in Kalinin — was almost certainly on his way to the “event” at the Ghanaian Embassy when he died. The same day, a few hundred students from Ghana and other African countries were said to be behaving unruly, driving Ghanian Ambassador and his wife to barricaded in a suit at the top floor of the building.

Various theories prevailed as to the origins of the summoning and the protest. A few potential culprits were unofficially named, including a few Western Embassies and even erratic Ghanian President Kwame Nkrumah who might have had his motives. However, the Soviet authorities stopped short of finger-pointing.

Instead, they closed the Assare-Addo case, expelled the most belligerent African students, discredited the protest in the eyes of the academic community and, finally, strengthened ideological education for foreign students. This is how the major protest of African students in the USSR ended.

Click here to find out why the USSR assisted African countries in becoming independent.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox