The BIGGEST defeat that U.S. troops suffered in Russia

U.S. soldiers await the ships that would carry them home in the summer of 1919.

U.S. National ArchiveThe early morning of January 19, 1919, in the village of Nizhnaya Gora in the Russian north was clear and frosty. American soldiers who had been billeted there were fast asleep in their beds when a sudden artillery barrage forced them to their feet. Running out into the street, they saw, just a few hundred meters away, ranks of white-clad Red Army soldiers rising from under the snow. That was how the battle which would largely determine the fate of foreign intervention in the Russian north during the Civil War began.

U.S. soldiers on Russian soil

A U.S. soldier pauses for a photograph while loading supplies onto a ship bound for Russia in 1918.

U.S. National ArchiveThe main reason that prompted the United States, Great Britain and France to send their troops to Russia was the signing of the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty on March 3, 1918, between the Central Powers and the Bolshevik government that had recently come to power in the country. If Russia quit the war, the Germans could unleash all their might on the French, which the Allies could not allow to happen.

That is why the governments in Washington, Paris and London decided to provide military and material support to the opponents of the Bolsheviks - the so-called ‘Whites’, who openly declared their readiness to fight against Germany to a victorious end. In addition, a huge amount of military cargoes earlier supplied by the Allies to the Russian army had accumulated in Russian ports and it was vital to make sure that they did not fall into the Bolsheviks’ hands.

A U.S. outpost in the wilderness of Russia's Far North.

U.S. National ArchiveIn the summer of 1918, more than 5,000 U.S. soldiers landed at the northern Russian port of Arkhangelsk. At about the same time, 8,000 more U.S. troops arrived in the Russian Far East, in order, among other things, to limit the territorial claims of their new geopolitical rival, Japan, which also participated in the intervention.

By the fall of the same year, the White Guard troops, with the support of foreign soldiers (mainly Americans and Canadians), advanced 300 km from Arkhangelsk to the south and occupied the town of Shenkursk on the banks of the Vaga River, wedging deep into the territory controlled by the Bolsheviks. Fenced by three rows of wire barriers, protected by numerous machine-gun nests and several dozen artillery pieces, the town became a bone in the throat of the Soviet command.

Shenkursk Operation

Americans in snow camouflage.

U.S. National ArchiveThe Red Army’s initial attempts to recapture Shenkursk in the fall failed and the main attack on the town by the Soviet 18th Infantry Division of the 6th Army was planned for January 1919. The division numbered 3,000 soldiers, as opposed to 300 Americans and 900 White Guards and Canadians.

The Red Army, with the support of the partisans, had to strike simultaneously from three sides, amid a harsh northern winter and without having any reliable means of communication. “I clearly imagined that were I to present such an operation to Professor General Orlov at the General Staff Academy, I would have never in my lifetime got a post at the General Staff,” the mastermind of the plan, a Soviet military leader and a former general in the tsarist army, Alexander Samoylo wrote in his memoirs Two Lives.

Bolshevik prisoners are fed rice by a U.S. soldier in January 1919.

U.S. National ArchiveUnits of the 18th Division secretly advanced towards Shenkursk and villages outside it, where the White Guards and the foreign troops were garrisoned. In temperatures of almost 40 degrees below zero and moving deep in snow, Red Army soldiers were also pulling heavy artillery with them.

To take the enemy by surprise, they were ordered to put their white underwear over their greatcoats, which served as camouflage and allowed them to approach within a hundred meters of the enemy positions unnoticed.

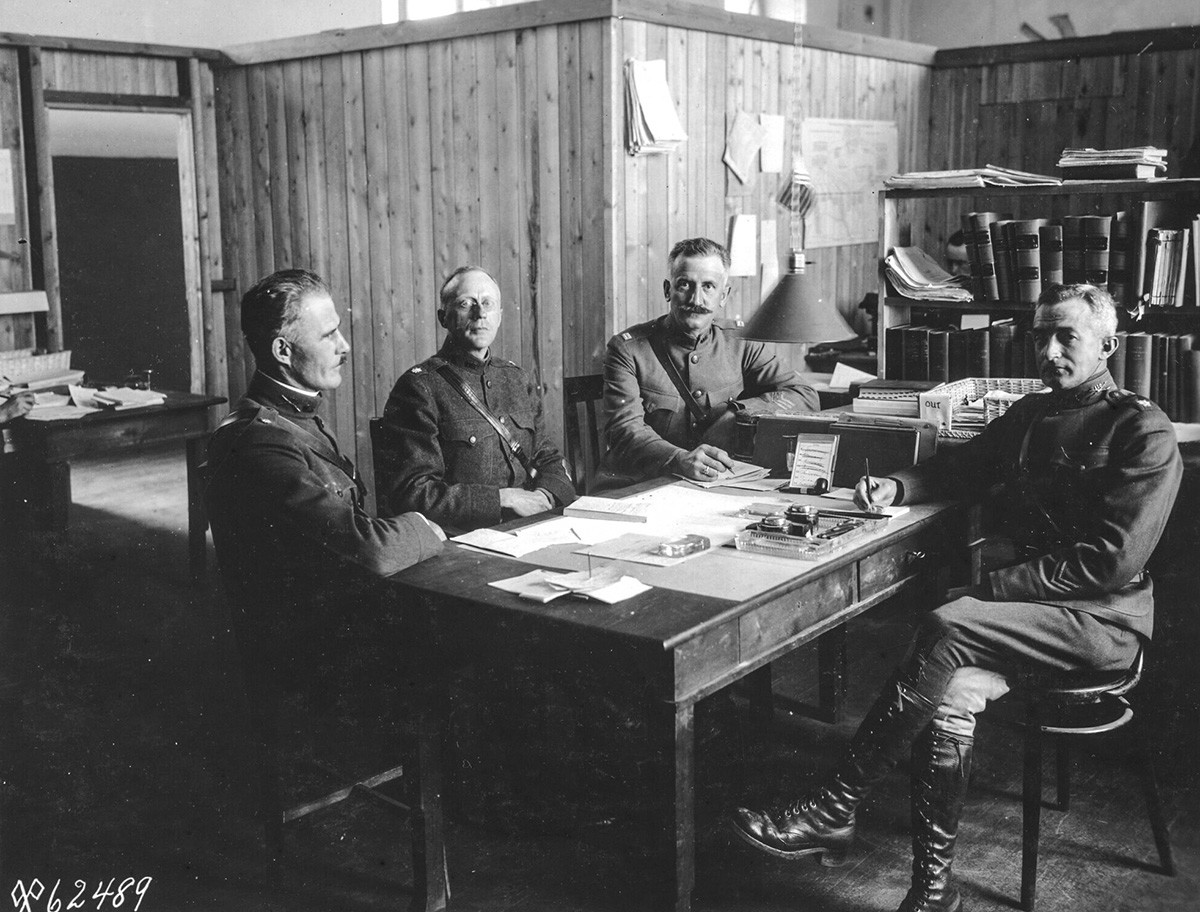

Officers of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Arkhangelsk in 1919.

U.S. National ArchiveThe appearance of Red Army soldiers with heavy artillery from what was considered impassable terrain stunned the enemy. Nevertheless, it took the Bolsheviks five days to drive the Whites, the Americans and the Canadians out of the villages and force them to retreat towards the town. “The snow was terrible, being waist deep, and, at every other step, some poor comrade fell wounded or dead. It was impossible to assist them as each man was fighting for his life,” Lieutenant Harry Mead recalled.

An assault on the town was planned for January 24. Without waiting for the attack, the White Guards and their foreign allies retreated from Shenkursk in a hurry towards the village of Vystavka along the only road that had not been cut off by the Reds.

Bitter defeat

American graves in Russia.

U.S. National ArchiveSoldiers of the 6th Army, who entered Shenkursk, took possession of military depots that contained 15 guns, 60 machine-guns and 2,000 rifles. There were also large food supplies in the town that were virtually intact. It was this factor that played a huge part in allowing the enemy to retreat: the hungry Red Army soldiers pounced on the food instead of pursuing the enemy.

As a result of the Shenkursk operation, the Whites and their foreign allies lost an important stronghold and were thrown 90 km back to the north. The American and Canadian troops alone lost up to 40 people, with about 100 wounded, which was a painful blow for the foreign forces, who usually tried to stay away from hostilities. By way of comparison, over the entire 18 months of their stay in the Russian Far East and Siberia, the 8,000-strong American Expeditionary Force Siberia lost only 48 servicemen, while just 52 were wounded.

U.S. troops line up for inspection before leaving Russia in June 1919.

U.S. National ArchiveThe Shenkursk fiasco became a heavy blow for the morale of the interventionists, sparking discontent among a number of American, British and French units, whose soldiers did not want to die in a war that was not theirs. It also was a contributing factor when the governments of the United States and their allies soon began to seriously consider the expediency and the cost of having their troops on Russian territory.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox