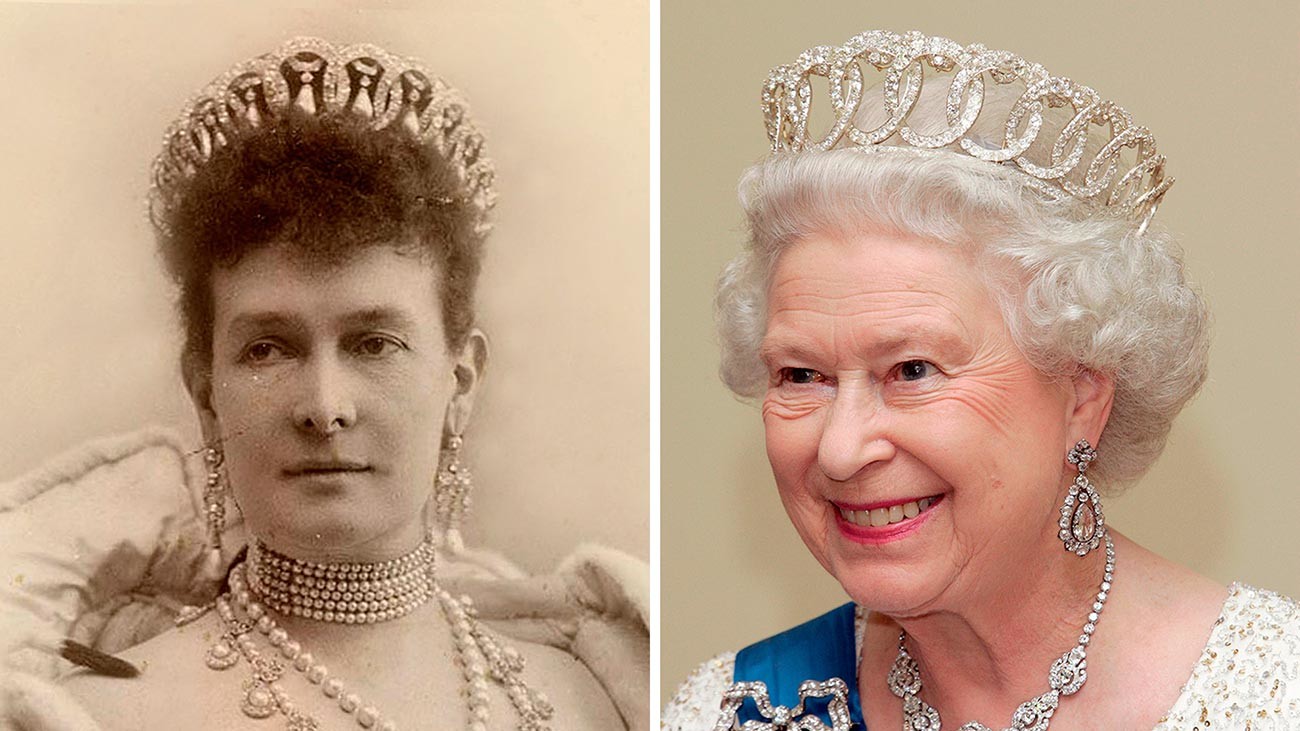

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna.

Kira Lisitskaya (Photo: Public domain; Legion media)The fact that female members of the last Russian Emperor’s family sewed diamonds into the corsets of their dresses became known after their execution: “The daughters… had beautifully-made bodices consisting entirely of diamonds and other precious jewels,” recalled Yakov Yurovsky, the chief executioner. Other Romanovs, however, were more fortunate and managed not only to escape with their lives themselves, but also clandestinely to smuggle their jewels, family gold and precious stones abroad. And sometimes this was done in the most ingenious manner.

Maria Pavlovna in her famous tiara.

Public domainGrand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (the spouse of Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia, Nicholas II’s uncle) was one of the few members of the Tsarist family who managed both to escape abroad after the 1917 Revolution and also to take part of her jewelry collection with her, albeit not personally. She carried almost nothing with her: All her valuables remained at home, but it proved possible to smuggle some of them abroad later. She was helped in this by Albert Stopford, a family friend and British diplomat (who, according to some historians, was also a British intelligence agent).

Vladimir Palace in St. Petersburg, the residence of Maria Pavlovna.

GAlexandrova (CC BY-SA 4.0)After the February Revolution, the Grand Duchess and her children (her husband had died a long time before, in 1909) left for Kislovodsk, having instructed the diplomat to find her jewels. There is only sketchy information about how he managed to do this. Maria Pavlovna allegedly told him about a “secret door” leading to her room in the Vladimir Palace in St. Petersburg. As the story goes, he got in by pretending to be a worker (according to another account - wearing a woman’s dress) and took out the jewelry wrapped in an old newspaper. After that, the diplomat went to Kislovodsk to hand the jewels to the Grand Duchess. But she took only a small part of her collection and asked Stopford to take the rest out of Russia to Britain and deposit it in a bank, details of which were to be known only by the two of them. It is known that in the fall of 1917, using his diplomatic immunity, Stopford left for London carrying 244 items of jewelry in his Gladstone bag.

Vladimir Tiara now belongs to the Queen Elizabeth II.

Public Domain; Getty ImagesIn 1920, Maria Pavlovna managed to leave Novorossiysk on an Italian ship bound for Venice, planning to then settle in France. However, she died soon afterwards and her jewels were inherited by her children. Her descendants sold many pieces from her jewelry collection in order to shore up their finances. Thus, the Vladimir Tiara now belongs to Queen Elizabeth II and her pearl-drop earrings to the spouse of Prince Michael of Kent.

A cigarette case showing the Grand Duchess and grandchildren is seen beside a pillowcase in which the lots were smuggled out of Russia, displayed during the preview of 'Romanov Heirlooms: The lost Inheritance of the Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna' at Sotheby's, London.

Anthony Devlin/PA Images/Getty ImagesBut the most interesting finds had to wait 90 years to be discovered! It emerged that, in November 1918, Maria Pavlovna, with the help of her friend, Professor of Painting Richard Bergholz managed to pass that part of her jewelry collection, which the trusted British diplomat had brought to Kislovodsk, and which she had held on to, to the Swedish mission in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg). The Grand Duchess didn’t have time to tell her relatives about the cache before she died and two pillowcases containing about 60 items of jewelry - Fabergé cigarette cases, gold cufflinks adorned with precious stones and other items - were only discovered in the archives of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2009.

Maria Pavlovna's sapphire brooch and earrings.

Press photoThe Swedes handed over the pillowcases to the descendants of Maria Pavlovna, who put them up for auction. Nowadays many of them are privately owned and turn up at auctions from time to time.

In addition to items taken out by representatives of the Tsarist family themselves, Romanov treasures were also taken out of the country with the permission of the Bolsheviks - the proceeds were supposed to pay for the needs of Communist movements in other countries. Foreign customs authorities repeatedly caught Comintern [Communist International] agents with suitcases full of jewelry.

John Reed.

SputnikAmerican journalist John Reed, who is buried by the Kremlin walls, witnessed the events of the Russian Revolution and wrote a book about them titled ‘Ten Days That Shook the World’. Furthermore, Vladimir Lenin personally wrote the book’s introduction. According to some historians, Reed was a Kremlin agent and, according to other accounts, he was a double agent. One way or the other, there is evidence that John Reed was more than just a journalist who sympathized with the Bolsheviks.

In March 1920, Reed was caught by customs officials in the Finnish city of Turku with diamonds hidden in the heels of his shoes. He insisted that he had purchased them with his own money, but he was not believed and was arrested. He was only released from prison in June that year.

Otto Kuusinen in Moscow.

SputnikAino Kuusinen, the wife of Finnish communist Otto Kuusinen, tells another interesting story in her memoirs. Agent Salme Pekkala was going to Britain on a mission for the Executive Committee of the Comintern. She received money for her “travel expenses” from Otto, who had just returned from Petrograd. “He produced four yellowish diamonds from the lining of his waistcoat which were about the size of a little finger,” Aino recalled.

In 2009, British intelligence declassified an archive file linked to the Romanov jewelry. In 1920, Francis Meynell, a director of the Daily Herald, sent pearls and diamonds belonging to the Tsar’s family, which he had received from the Bolsheviks in Sweden to Britain. They were hidden inside chocolates and dispatched by post. Later Maynell said that, eventually, all the jewelry went back to the USSR.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox