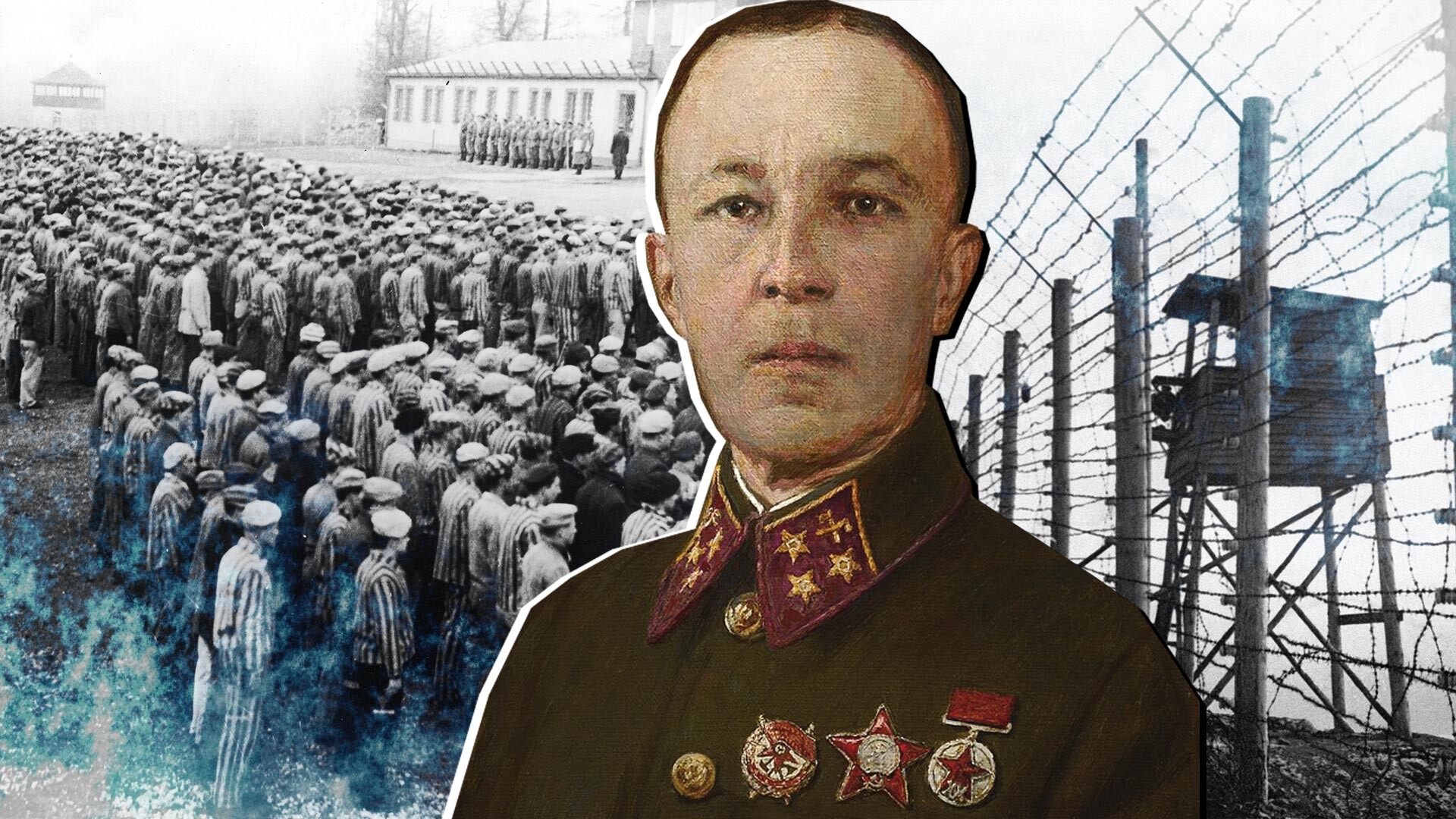

Lieutenant General of the Engineering Corps Dmitry Mikhailovich Karbyshev was one of the most valuable personnel in the Red Army. When Germany invaded the USSR in 1941, the 60-year-old commander had already seen four wars and won numerous tsarist and then Soviet medals.

Karbyshev demonstrated immense courage on the battlefield during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, and later distinguished himself as a highly capable fortifier. During the Russian Civil War, he successfully led the construction of seven fortified areas in the Volga region and Siberia, and provided engineering support for the assault on the enemy's defensive positions on the Crimean Peninsula.

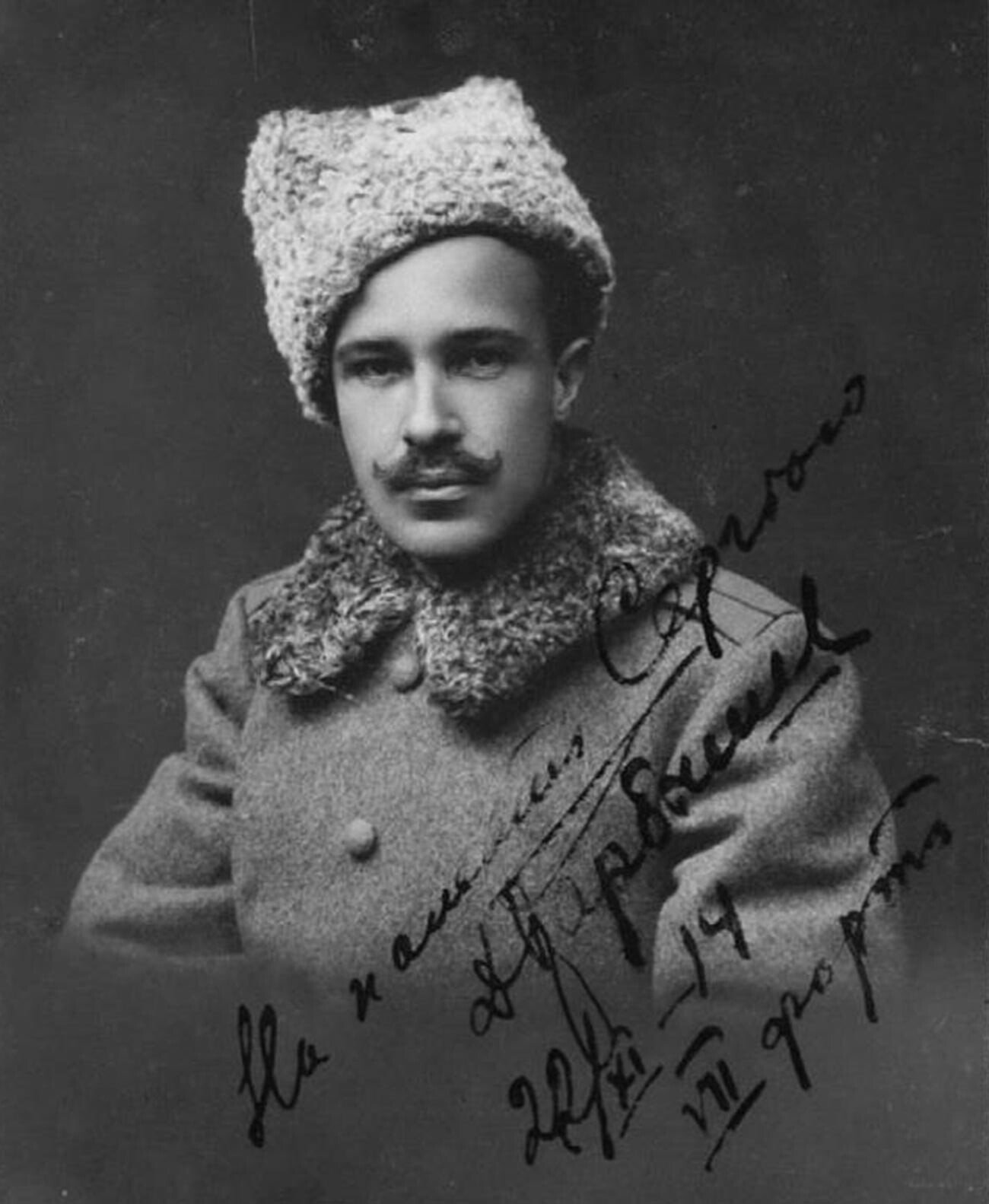

Dmitry Karbyshev in 1914.

Public DomainDuring the Winter War against Finland, the now Soviet commander personally reconnoitered the Mannerheim Line, a Finnish defensive fortification on the Karelian Isthmus, and his recommendations were vital for breaking through.

A doctor of Military Sciences, Karbyshev authored more than a hundred academic publications on fortifications and military history, and pioneered the use of engineering obstacles. His works formed a core component of the military training of the Red Army command.

Soviet soldiers near the destroyed Finnish pillbox.

Public DomainIn the summer of 1941, the general was inspecting the construction of the Grodno (Hrodno) fortified region in western Belarus when he was caught by a devastating blitzkrieg. In August, while trying to escape the encirclement, Karbyshev was captured. The Germans were quick to realize what a vital asset had fallen into their clutches.

Karbyshev was offered royal treatment in return for cooperation: release from the POW war camp, his own separate lodgings, full material support, access to libraries and archives, personal assistants, the opportunity to write academic papers, conduct any research and work on any projects. He was permitted to go to the frontline and check his analysis in the field.

Soviet POWs.

BundesarchivBerlin was confident there would be no issues with recruiting the Soviet general. It was thought that this former nobleman and tsarist officer who spoke excellent German (his first wife was German) would jump at the chance to serve the Third Reich.

But things didn’t go according to plan. The commander categorically refused to cooperate, and no amount of promises could lure him. So the Germans turned to intimidation, threats and torture, steadily worsening the conditions of his detention. But that didn’t work either.

Prisoners in Mauthausen.

BundesarchivAfter two years of fruitless attempts, the Nazis gave up. “This key Soviet fortifier, a regular officer of the old Russian army, a man over sixty years old, proved fanatically devoted to the concept of loyalty to military duty and patriotism…” read a German report from 1943: “All efforts to engage Karbyshev as a military engineering specialist are futile.”

The general’s fate was decided: hard labor at the Flossenbürg concentration camp, with no mitigation on account of rank or age.

The fearless commander was transferred from one camp to another. He survived Auschwitz and Sachsenhausen, but Mauthausen, where Karbyshev was taken in February 1945, was to be his last refuge.

Hero of the Soviet Union Dmitry Karbyshev.

SputnikCanadian Army Major Seddon de St. Clair, a fellow POW, witnessed the death of the general: “As soon as we entered the Mauthausen concentration camp, the Germans drove us into the shower room, ordered us to undress and sprayed ice-cold water on us from above. This went on for a long time. Everyone turned blue. Many fell to the floor and died: the heart couldn’t take it.”

Karbyshev, who was in his sixties, miraculously survived. He and the others were ordered to put on underwear and wooden blocks on their feet, and then led out into the yard in the freezing cold. “General Karbyshev was standing in a group of Russian comrades not far from me,” St. Clair recalled. “We knew our time was up. After a couple of minutes, the Gestapo henchmen, who were standing behind us with hoses, fired streams of cold water at us. Those who tried to dodge the jet were bludgeoned over the head. Hundreds of people fell to the ground frozen or with crushed skulls. I saw how General Karbyshev was one of them.”

Back in the Soviet Union, nothing was known about the fate of Dmitry Karbyshev, and he was filed as missing in action. Only after the war, bit by bit, were the last years of his life pieced together.

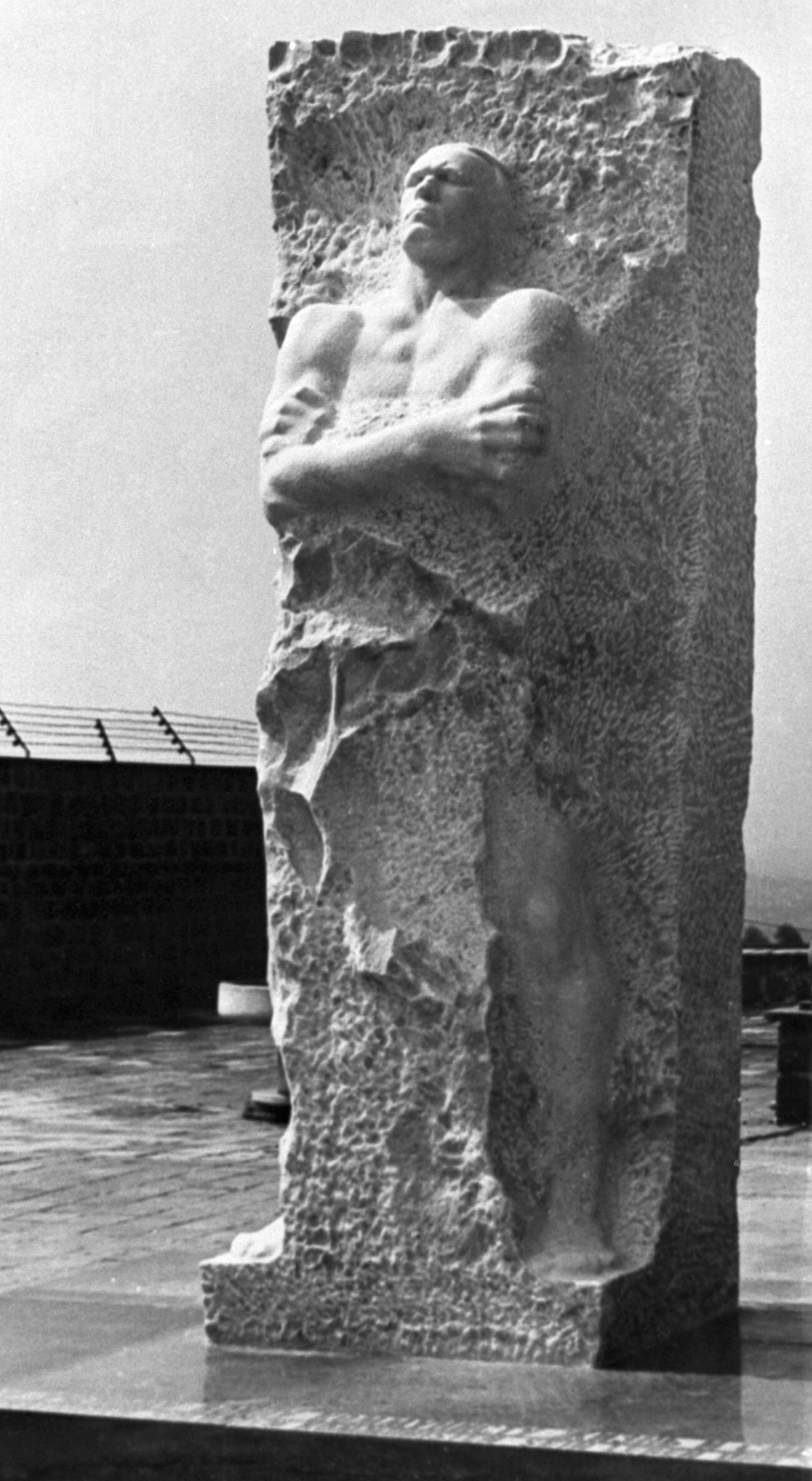

Memorial to general Dmitry Karbyshev in Mauthausen.

Lev Ivanov/SputnikOn Aug. 16, 1946, Lieutenant General of the Red Army Engineering Corps Dmitry Karbyshev was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union “for exceptional courage and resilience in the fight against the German invaders in the Great Patriotic War.”

Two years later, there in Mauthausen, a monument was put up to the commander with the inscription: “To Dmitry Karbyshev. Academic. Soldier. Communist. His life and death were an act of heroism in the name of life.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox