Cells with sumbergeable floors that sent you to your death from being devoured by predatory fish; weapons of torture hanging on walls all around and capable of breaking even the most unwilling; unknown prisoners in damp casemates, in the company of silent, unwavering guards: such were the descriptions, conjured up by the imaginations of ordinary people of the most evil of all tsarist prisons – Shlisselburg.

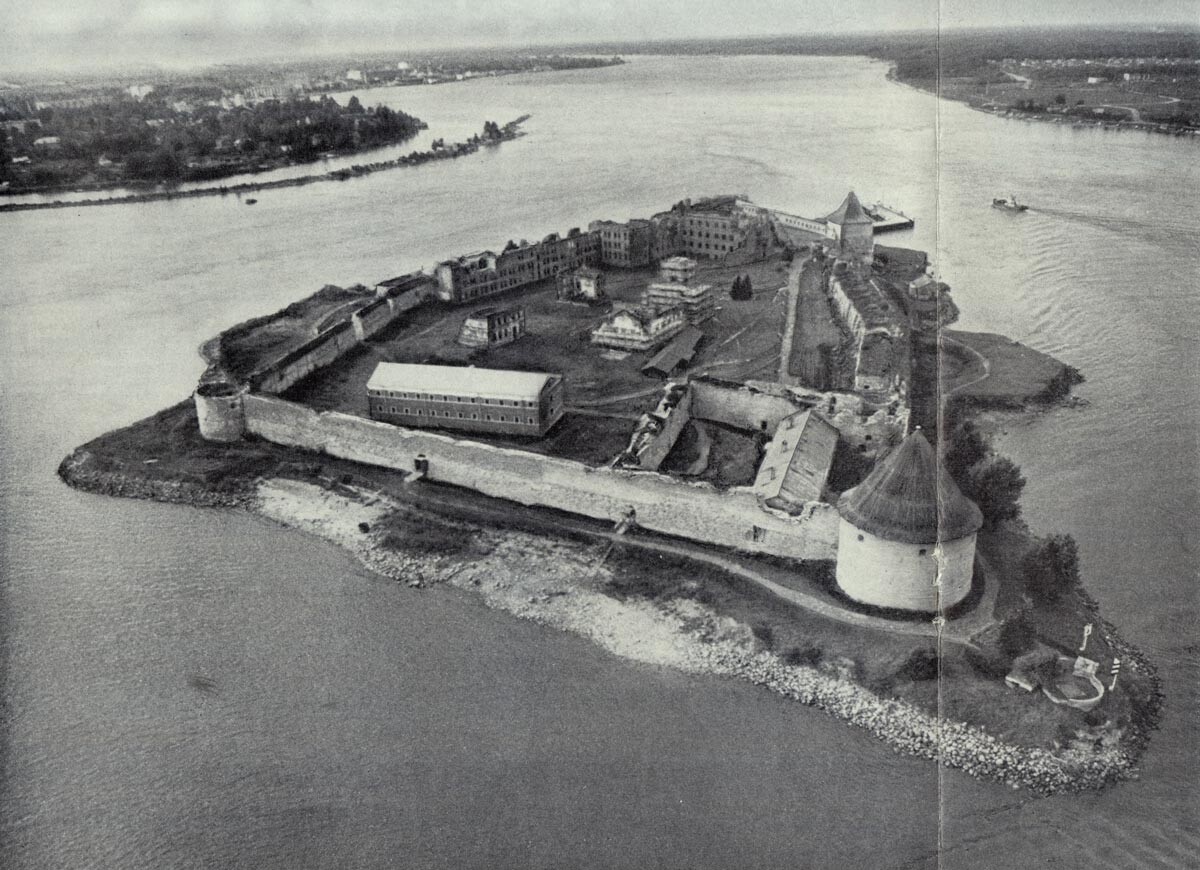

This prison was located on an island in Lake Ladoga, at the mouth of the Neva River. The shores were lined with sharp granite boulders and the current was so strong that making a journey was difficult and escaping impossible. The giant rock had all manner of dark legends surrounding it, but reality was occasionally quite different.

The Shlisselburg fortress in the early 18th century

A. Varfolomeev/SputnikAlready at the start of the 18th century, the old Novgorod stronghold of Oreshek, won over by Peter I from the Swedes, lost its military purpose and went on to be a political prison for years to come. The first prisoners were the closest relatives of Peter himself – first, his sister, 58-year-old Princess Maria Alekseevna, who spent three years there. Later, after the death of the autocrat, his first wife – Evdokia Lopukhina, was also imprisoned there, in a cell with a single window. Catherine understood Evdokia posed a threat to her position as an Empress after Peter's death. When, after two years of wild, unadulterated fun, 43-year-old Catherine finally passed away and Evodkia’s grandson Peter II took the throne, she was finally free to leave the prison and return to the Kremlin with all the appropriate honors befitting a royal.

However, Shlisselburg did not stay empty for long and, soon, new casualties of court intrigue had begun to appear, the most famous of which was the deposed emperor Ivan VI. Having ascended the throne as an infant, he “ruled” a little longer than a year, before being removed from power by Peter and Catherine’s daughter Elizabeth. She wished to preserve the child’s life, but kept him locked up for the sake of avoiding turmoil.

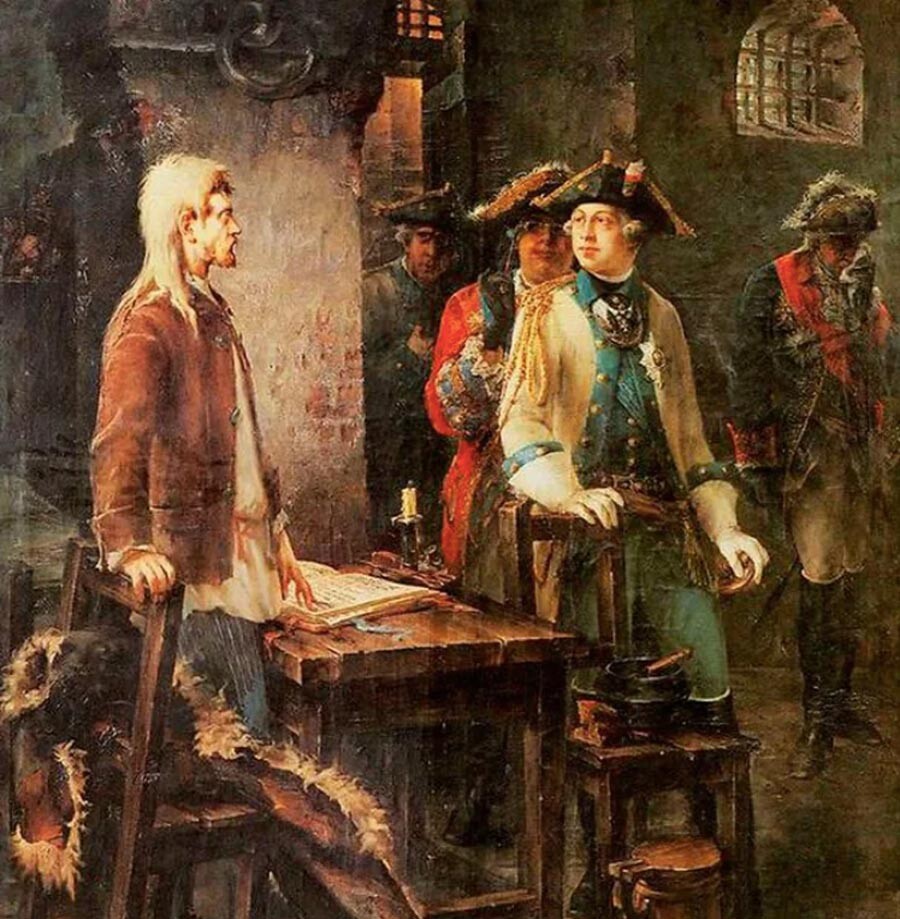

"Emperor Peter III visits Ivan VI Antonovich in the Shlisselburg Fortress , 1762," by Fedor Burov, 1885.

Public DomainBefore ending up on the island, Ivan would change several places of imprisonment. He would spend eight years at Shlisselburg’s specially guarded quarters. The guards were instructed not to speak to him – let alone tell him who he is and why he was there in the first place. His face was even concealed from the servants with the use of a special screen. The only thing the prisoner had had more than enough of was food. Although it would later be discovered that his guards not only went against the orders given to them – telling the young boy about his true identity, but he also knew how to read. On the night of 5-6 July, 1764, tragedy struck: the poor boy was stabbed to death by those very guards during an attempt to break him out of Shlisselburg. Such were the instructions in the case of this happening.

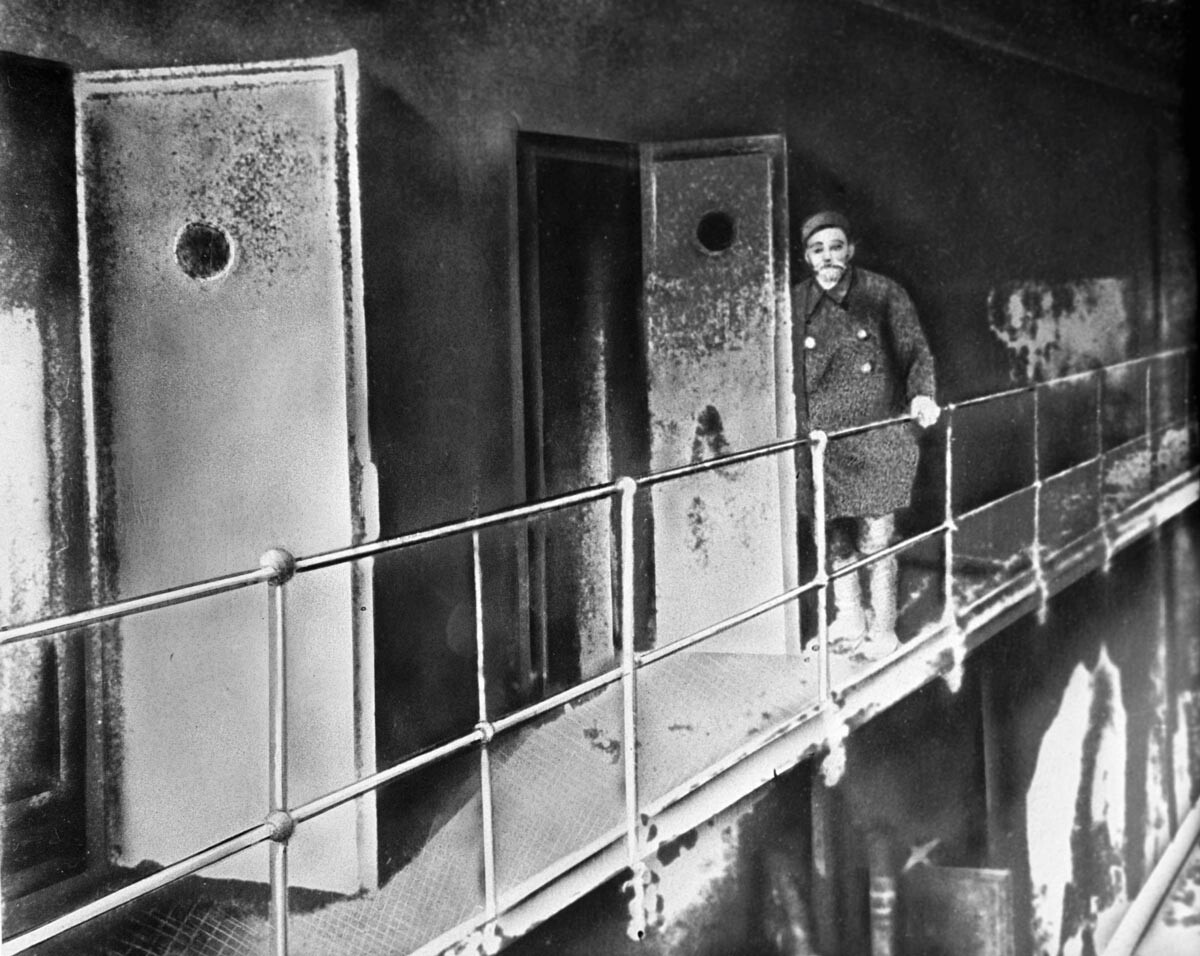

A cell in the Shlisselburg fortress

Legion MediaWith the passing of years, the morbid-looking prison stronghold wound up taking in fewer and fewer guests of noble beginnings and, instead, began imprisoning greater numbers of regular folk: there were a lot of rebels and freethinkers, such as Decemberists that managed to avoid execution. In 1884, Shlisselburg received the transfer of ‘Narodnaya Volya’ (‘People’s Will’) revolutionaries from the Peter and Paul Fortress, charged with the murder of Aleskandr II. There were 36 in the first year, with their warden also being transferred from the St. Petersburg prison they were held in: a man by the name of Matvey Efimovich Sokolov, nicknamed ‘Herod’, for his cruelty. Sokolov was as merciless as he was a stickler for observing the chain of command: “If they tell me to address the prisoner as: ‘Your Excellency’, I will address them as ‘Your Excellency’. If I’m ordered to strangle them to death – I’ll strangle them,” he would say.

There was no court shown to tsar-killers in the early years: poor food, an even worse library, consisting of nothing but religious literature, a ban on correspondence with relatives, solitary confinement for communicating with other inmates by knocking on walls – and death, for daring to insult the prison personnel. Many inmates succumbed to scurvy and tuberculosis, or simply went mad. The only activity for young and energetic prisoners – which most of the rebels were – was fighting the administration.

The Shlisselburg fortress, aerial view, 1988

"Nevskaya Panorama" magazine, 5/1988This battle usually took on the form of complaints and hunger strikes, although, sometimes, inmates would resort to more drastic measures by attacking the wardens, doing so in the hopes of being put out of their misery. One fiery revolutionary, Yegor Minakov, who’d escaped hard labor numerous times prior to ending up at Shlisselburg, did not wish to become a “rotting deck, submerged underwater”. He demanded visitation rights with family, books and tobacco and went on a hunger strike. Several days after laying out his demands, a doctor forcefully fed him milk, with Minakov striking him in the face and, in so doing, ending his life by means of a firing squad. Another revolutionary, Ippolit Myshkin, threw his plate at Sokolov and was also executed. Hoping for the same outcome, terrorist Mikhail Grachevsky tried the same tactic, but was deemed mentally unfit and spared from exectuion. He then chose to douse himself in kerosene from a gas lamp and set himself on fire. The gendarmes on shift had tried to save his life, but the cell’s door was shut tight, with Sokolov being the only one who had the key.

Russian revolutionary Vera Figner remembered years later: “There, beyond the door, a tall slim figure with a matt face of a living dead man just stands. Stands and gradually darkens in the flames and clubs of soot and smoke. The fire licks the man with its red tongues, fire – from top to bottom, from all sides. The torch burns and smokes – a living creature, a man!”

Vera Figner (1852-1942)

Public DomainWhen ‘Herod’ finally came to the cell – a whole ten minutes later, it was too late. For such a glaring oversight, Sokolov was strongly reprimanded and, soon thereafter, relieved of duty. Other ranking guards, having witnessed such horrors, in time softened up and the inmates’ life at Shlisselburg began to gradually improve.

Gradually, the prisoners managed to attain some privileges never before experienced by state criminals. This was in large part due to the work of the prison’s commandant Colonel Ivan Gangardt. The famous revolutionary Vera Figner confessed: “For all of the major positive changes to our lives, we owed a debt to Gangardt. It was he who rid us of the vengeful hand of the Department of the Police and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. He understood that the loss of freedom, the renunciation of life’s work, the loss of all family and friendly ties – all are in themselves severe forms of punishment that few men could handle and to add to that would have simply been excessive.”

This change in attitude toward the People’s Will members was partially down to widespread public support for revolutionary terrorism, which stood in the way of applying ever harsher measures to the regime’s opponents. Even writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky confessed that he would not have been able to give up a terrorist to the police out of fear of public condemnation. As for the gendarmes, given the inertial concept of class divisions, these political prisoners, who were part of the educated intelligentsia, did not present a faceless evil.

The Shlisselburg fortress, contemporary photo

Petr Kovalev/TASSBy the end of the 19th century, the inmates had been living in two-room, well lit and warm cells with electrical lighting and outfitted with modern closets. They had a wonderful library, even ordered magazines – including ‘The Times’ (the highly educated People’s Will members read and spoke foreign languages). They could also have control over the menu, agreed ahead of time, and even tended to their own gardens and flower beds. And the prison had its own workshops and forge. The Department of the Police provided the funding for the purchase of the above magazines, literature, flower seeds, tools and other necessities.

Inmates took walks, held lectures, made fruit preserve, were allowed to smoke, made herbariums and mineral collections and even held dances. The latter was over and done with after Figner quarreled with one of the gendarmes and tore off his stripes. The prisoners even managed to build a moonshine maker, although it was quickly found and confiscated. Some of the more brave ones managed to set up a lucrative trade system with the wardens. They would sell vegetables from the patches. There was no money exchanging hands, but, in return, they could order produce and art supplies.

The gardens of the inmates at the Shlisselburg fortress

Public DomainPrisoner Vasily Ivanov set up a water fountain. Revolutionary Peter Polivanov studied English, Italians and Polish. The unwavering and tireless popularizer of science and revolutionary theoretician Nikolay Morozov studied math, physics, astronomy and chemistry, while managing to pen a scientific essay on the molecular structure of matter… albeit with conclusions that were found to be false later.

Vera Figner would remember these days in the following way: “Inside, we were the masters of our circumstances. If there was any noise or the sound of voices, yells or someone scolding somebody, they always came not from the prison wardens, but from one of the inmates… It wasn’t the warden yelling – he was the one being yelled at." Even the occasional arrival of death row inmates would be organized in such a way that the other inmates were kept unaware of what was happening, to prevent them from raising a ruckus. Gallows would be constructed at night, quietly.

The overseer stands at the cell of Nikolai Alexandrovich Morozov in the Shlisselburg Fortress

SputnikThe life of the gendarmes stationed on the island had barely any more variety than that of their wards. They spent their boring work days reading Jules Verne and Mayne Reid, collecting mushrooms and infusing liquors, which they then gleefully consumed over card games. They played from dusk until dawn, then had tea and went their separate ways. They would then get a day off after the tense card game.

One eye witness described the scene: “These gentlemen, all green and tired from lack of sleep, their faces twisted with greed, especially their wives… In a word, that entire gang, to a regular onlooker, might have appeared mentally ill.” One of the gendarmes’ wives, in order to somehow offset her husband’s constant losses, would lock away all his clothes before the above-mentioned card game nights and he’d stay sitting home in nothing but underwear. The junior officers living in the stronghold had many children, so the sinister-looking rock was often full of not just military commands, but children’s voices as well.

In 1905, after the first Russian Revolution, the old way was no more and numerous prisoners were amnisted or transferred. In any case, the stronghold was soon turned into a regular hard labor camp, accepting not only those accused of high treason, but regular criminals as well. From that point on, Shlisselburg finally lost its mysterious and unique aura, having been turned into a run-of-the-mill-prison. Later, in 1917, the rock was captured by a revolutionary crowd. The freed hardened criminals ransacked and set the place on fire. That was the end of the tsarist “Bastille”.

The Shlisselburg fortress, aerial view

Petr Kovalev/TASSToday, the former dungeon is an open-air museum that can be visited from May to October. There are even historical reenactment games for children, based on the various historical epochs, dating back to the medieval period and extending all the way to World War II. Instead of hard rye bread, the food today has been replaced by mulled wine and hot dogs. The former cells, meanwhile, now contain curious visitors, instead of inmates. The dark period of Shlisselburg stronghold’s history has long been left behind.

To keep up with our latest content subscribe to our Telegram channel!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox