Zinaida Zhuchenko (née Gerngross) was a legend among the secret police circles of the Russian Empire of the late 19th century. Starting her career as a modest home tutor, she turned into one of the most notorious enemies of the Russian revolutionary underground, snitching on people who considered her their friend – but in Zhuchenko’s ethics, it was all justified by a good cause – saving Russia from terrorist attacks the revolutionaries tried to carry out. However, her story didn’t end that well.

“My dear friend! I only fear one thing: sulfuric acid! I’m starting to think they will not kill me. It is quite difficult, after all. They are certain that I’m surrounded by a swarm of police. And ‘it would be a pity to sacrifice one of the good ones for a provocateur’, they appear to believe, I think. Perhaps, it will come down to sulfuric acid,” wrote the secret agent of the tsarist police, whose cover was blown, in a letter to her former chief, Mikhail von Kotten in August, 1909.

Several days prior to the correspondence, Zhuchenko, who had been on active duty since 1894, was exposed by the “Sherlock Holmes of the Russian revolution” – emigrant journalist Vladimir Burtsev. Thorough and relentless, Burtsev ambushed Zhuchenko right at her home in Berlin, where she had been living with her teenage son and a friend. The evidence was irrefutable. It was pointed out by acting State Councilor Sergey Kovalensky, head of the entire Russian political investigative unit. Following a swift resignation from the post of Director of the Department of Police, his career fizzled out and he’d apparently considered himself slighted, which appears to have pushed him to commit treason, then suicide. His testimony was backed up by Leonid Menshikov, another defector.

Burtsev, being a seasoned tsarist agent hunter, expected the usual tears, resistance, hysterical pleas and claims of innocence from the meeting. But he got something entirely different.

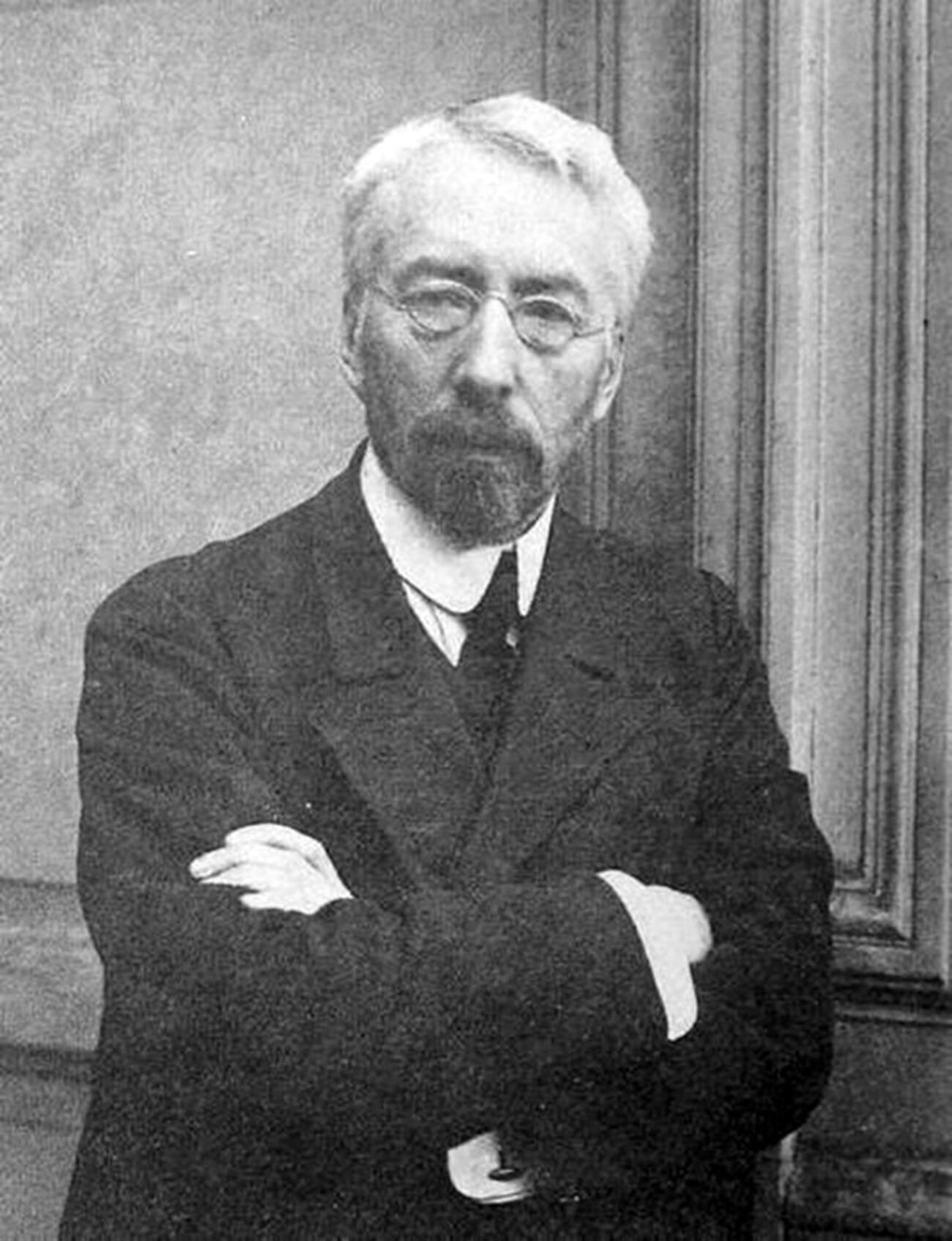

Vladimir Burtsev, the journalist who broke Zhuchenko's cover

Karl Bulla“You delivered a blow to my most sacred ideals, ones I live my entire life by… You are an incredible type – I think, think of you, and so strongly desire to understand you better,” he wrote Zhuchenko after that fateful meeting. In her – a stern-looking woman that rather resembled a teacher, the old lone wolf revolutionary saw an adversary he considered to be his equal – something that had never happened to him before. What’s more, even officials at the investigative unit had to wonder if they’d ever had the pleasure of working with such a gifted undercover operative – one who served not for money or out of fear or a desire to harm their former cohorts. Zhuchenko was one of a kind.

Having graduated from the Smolny Institute in 1893, 22-year-old Zinaida Gerngross used to tutor a police official’s children; she was able to strike up a friendship with other police officials at the Ministry of Internal Affairs thanks to this, including the legendary detective Sergey Zubatov. Having become Zubatov’s protege, she infiltrated a secret group run by a student named Ivan Rasputin, which planned to assassinate the tsar at his crowning ceremony. The group’s plans were foiled as a result. Having been arrested in 1896, together with the ill-fated tsar murderers, Zinaida – now an undercover agent – spent a year in prison, before being sent off to the Caucasus. It was there that, according to her, she committed the biggest mistake of her career – getting married. Her husband turned out to be a violent type and she fled to Germany with her infant son Nikolai.

In 1905, she was asked to return to duty. The first Russian Revolution was flaring up and the feisty Zhuchenko jumped straight into the fire, to the barricades, with no regard for her safety.

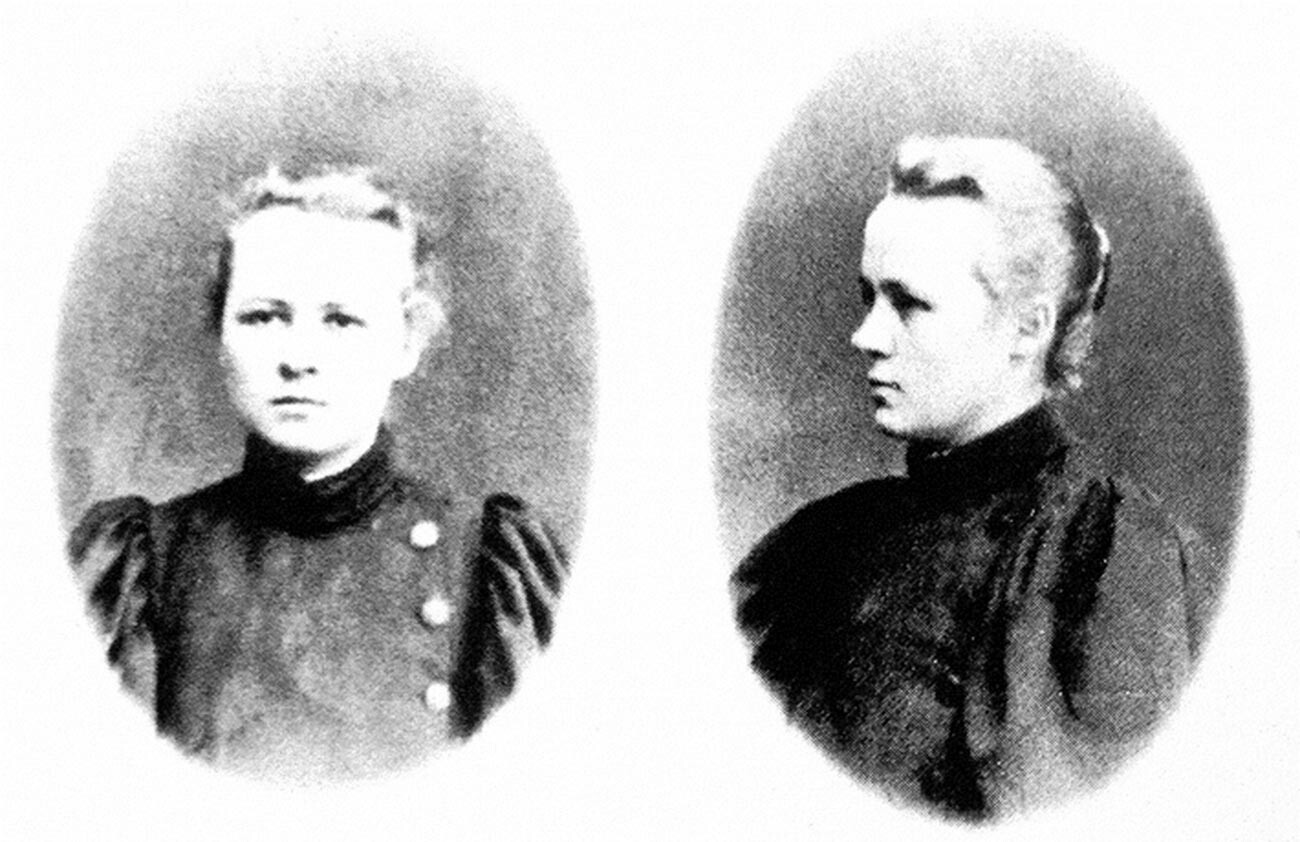

Zinaida Zhuchenko, mugshot

Public domainThere, Zhuchenko wasn’t simply an operative with the secret police – she became a friend and confidante of her gendarme superiors. Moscow Security Department heads Evgeniy Klimovich and Mikhail von Kotten heeded her advice, respected her as a person and regularly hosted her in their homes as an esteemed guest. She repaid the kindness by working tirelessly: among other things, two of the most high profile assassination attempts were foiled. In early 1906, socialist-revolutionary party members decided to settle the score with Minsk governor Pavel Kurlov for shooting up an anti-government demonstration in Minsk in October 1905 – an incident that became known as “the Kurlov shooting”. They ended up throwing an explosive at Kurlov, hitting him in the head, but failing to explode. This was because Zhuchenko, who was tasked with delivering the bomb to Minsk, first took it to Von Kotten, who extracted the detonator.

A year later, in February 1907, revolutionary fanatic Fruma Frumkina decided to shoot Moscow mayor Anatoly Reynbot and told her party cohorts she would commit suicide if they stood in her way. Zinaida understood that changing Frumkina’s mind would have been impossible and prepared her for the mission, stitching a special pocket for a revolver; she then aided in Frumkina’s capture at the entrance to the Bolshoi Theater, where she planned her attack.

As irony would have it, the lives Zinaida saved left a lot to be desired as people: Kurlov positioned himself as a corrupt sycophant and conniving lover of intrigue, while Reynbot – a short time after the assassination attempt – was charged with stealing from the treasury and other corrupt practices.

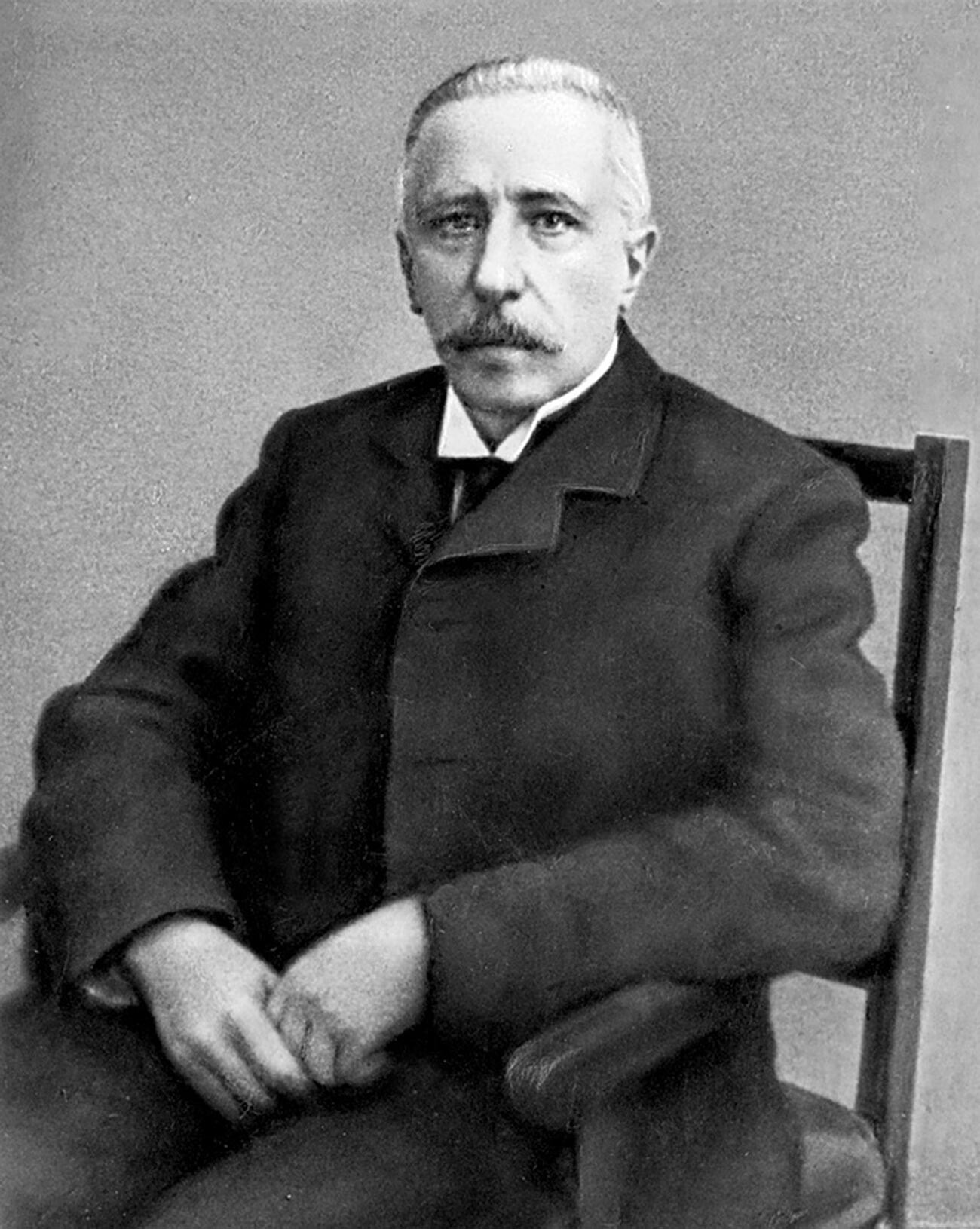

Pavel Kurlov, the governor Zhuchenko saved

Public domainDespite her chivalrous loyalty to the government, as well as her school teacher looks, Zinaida was no ‘girl next door’ type: she had a morphine habit, had a tendency for love affairs with revolutionaries, with a particular taste for the rougher ones – and what the lovers trusted her with during their steamy love-making sessions, she readily reported to her comrades at the department.

The revolutionaires themselves never allowed a sliver of doubt to form as to Zhuchenko’s own reliability. So, if it weren’t for her former police colleagues Kovalensky and Menshikov’s betrayal, she would have, in all likelihood, continued her sterling career. Burtsev, hungry for every small detail, promised Zhuchenko her life in exchange for information, but the operative not only refused to berate her former superiors, but engaged in lengthy debate with her accuser. This active correspondence between the two irreconcilable adversaries lasted for several years. Zhuchenko’s aim was to destroy the revolutionaries’ – as well as the entire opposition camps’ – stereotypical views of the secret operative as a saboteur and a corrupt human being.

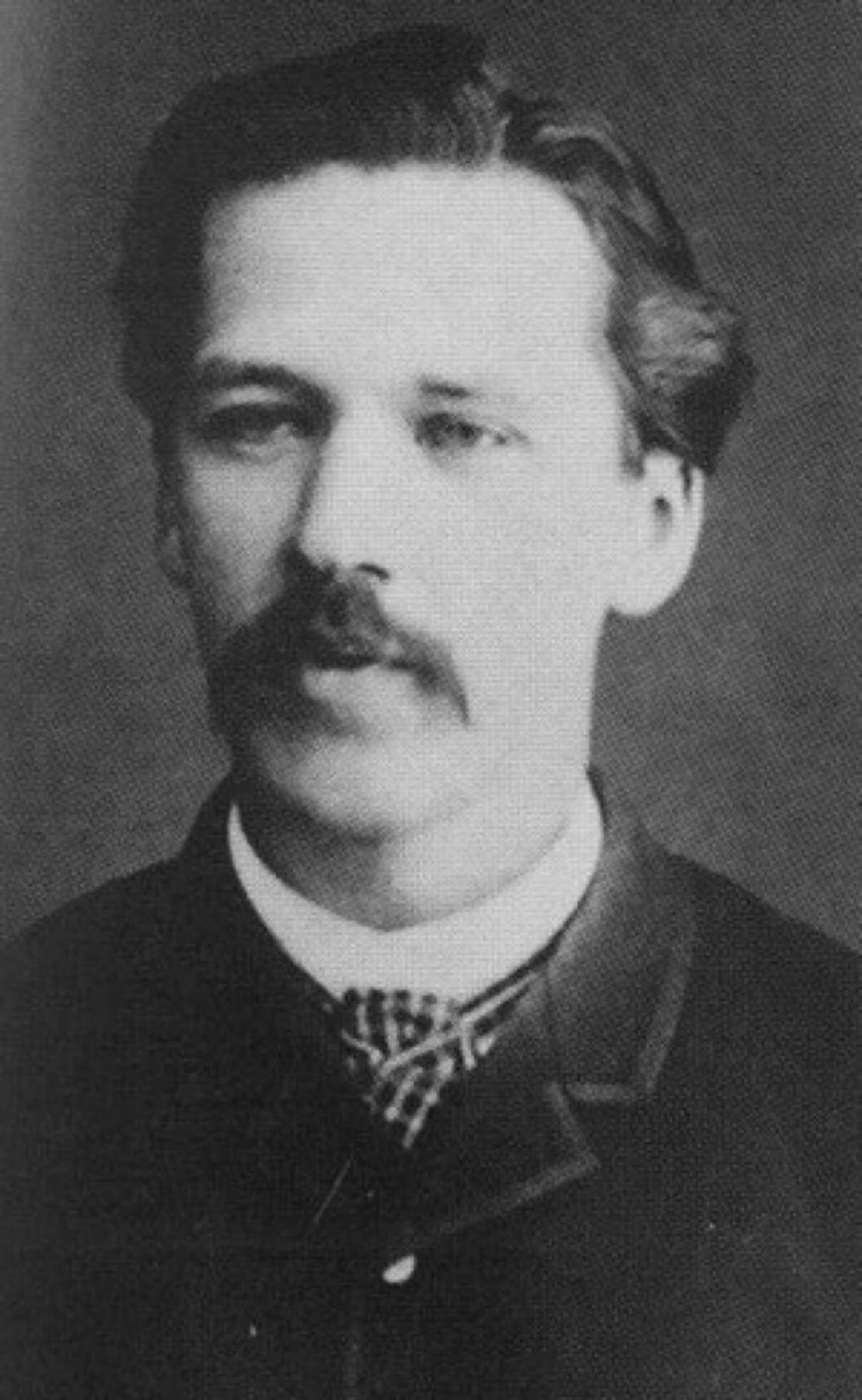

Sergey Zubatov, a famous Russian police administrator and Zinaida Zhuchenko's boss

Public domainPerhaps, owing to Zhuchenko’s ideological position, which the revolutionaries could not help but admire, the former undercover operative managed to escape a bloody reprisal. She lived a quiet, solitary existence in Berlin on an ample pension from the Russian government. This lasted until the beginning of World War I. The Berlin police, which at one point enjoyed a cozy relationship with the tsarist police, was informed of Zhuchenko’s role and, with the start of the war, arrested her as a potential spy, taking away her 16-year-old son for good measure. Zinaida spent the next three years in a female prison before being transferred to the Havelberg concentration camp.

Upon release, she was greeted with new challenges: her relationship with son Nikolay had soured after prison – he did not share his mother’s ideals and, even as a young man, visited journalist Burtsev at his home, which the latter wasted no opportunity gloating about. And now, Nikolay decided to go to his father in Turkestan, a region in Central Asia. It is not known whether he managed to reach his destination – revolution had struck in Russia.

Having received early news of the coup in Petrograd, Zubatov, so beloved by Zinaida Fedorovna, used a gun to take his own life. Several days later, an enraged crowd at Helsingfors (now Helsinki) practically tore Von Kotten limb from limb. However, even Burtsev’s feeling of triumph at his revolutionary comrades’ victory did not last long. By the mercy of the Bolsheviks, he found himself at the Peter and Paul Fortress (St. Petersburg), where he used to be an occasional guest during Nicholas II’s reign. While there, he was neighbors with highest-ranking police officials, many of whom were soon executed.

Revolutionary soldiers in Petrograd, 1917

Public domainBurtsev managed to get free and leave for Paris, where Zhuchenko resumed her letters to him in the hope that he would help her locate her son. According to information she had at the time, he was taking part in the Russian Civil War. Having not received any word from Nikolay, Zinaida thought him to be dead. “In a word, it’s hard… But personal grief is entirely consumed by the one felt for Russia,” she wrote.

In 1924, Burstev received the final letter from his “earnest enemy”. Zhuchenko wrote that her son had returned home alive and unscathed, while she herself continues to live in Liege, Belgium, selling tickets to dances. “Meanwhile, my own little mission has turned to history, justified by it and… my attitude to its appraisals – whether they come from the enemy or the friendly camp – is entirely calm and objective. In all actuality, we Russians are only left to lament an irretrievable, deceased past… The present, for the two of us – while something very pleasant, has been colored by this mourning.”

Zhuchenko’s fate from then on is unknown, as well as the time and place of her death – she simply disappeared.

Burtsev died in occupied Paris on August 21, 1942. According to writer Aleksandr Kurpin’s daughter’s memoirs, “Burtsev – until his final days – continued to walk the desolate, frightened city, worrying, quarreling with and trying to prove to people that Russia would win…”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox