Great Prince Svyatoslav Igorevich of Kiev always preferred war to all other pursuits and even affairs of state. “Alexander (Macedonian) of our ancient history”, as the Russian historian Nikolai Karamzin characterized Svyatoslav, fought without respite against the near and distant neighbors of Rus’: Khazars, Pechenegs, Bulgarians and Byzantines.

Svyatoslav appeared on the battlefield for the first time at the age of four, when his mother Princess Olga took revenge on the Drevlyan tribe for the treacherous murder of her husband Prince Igor. Sitting on horseback, the future commander tried to throw a spear at the enemy. It flew between the ears of the horse and struck him at his feet. Voevoda Sveneld, seeing this, said: “The prince has already begun; let’s follow the prince, druzhina (a band of experienced warriors presided over by a prince)!” The enemy was defeated.

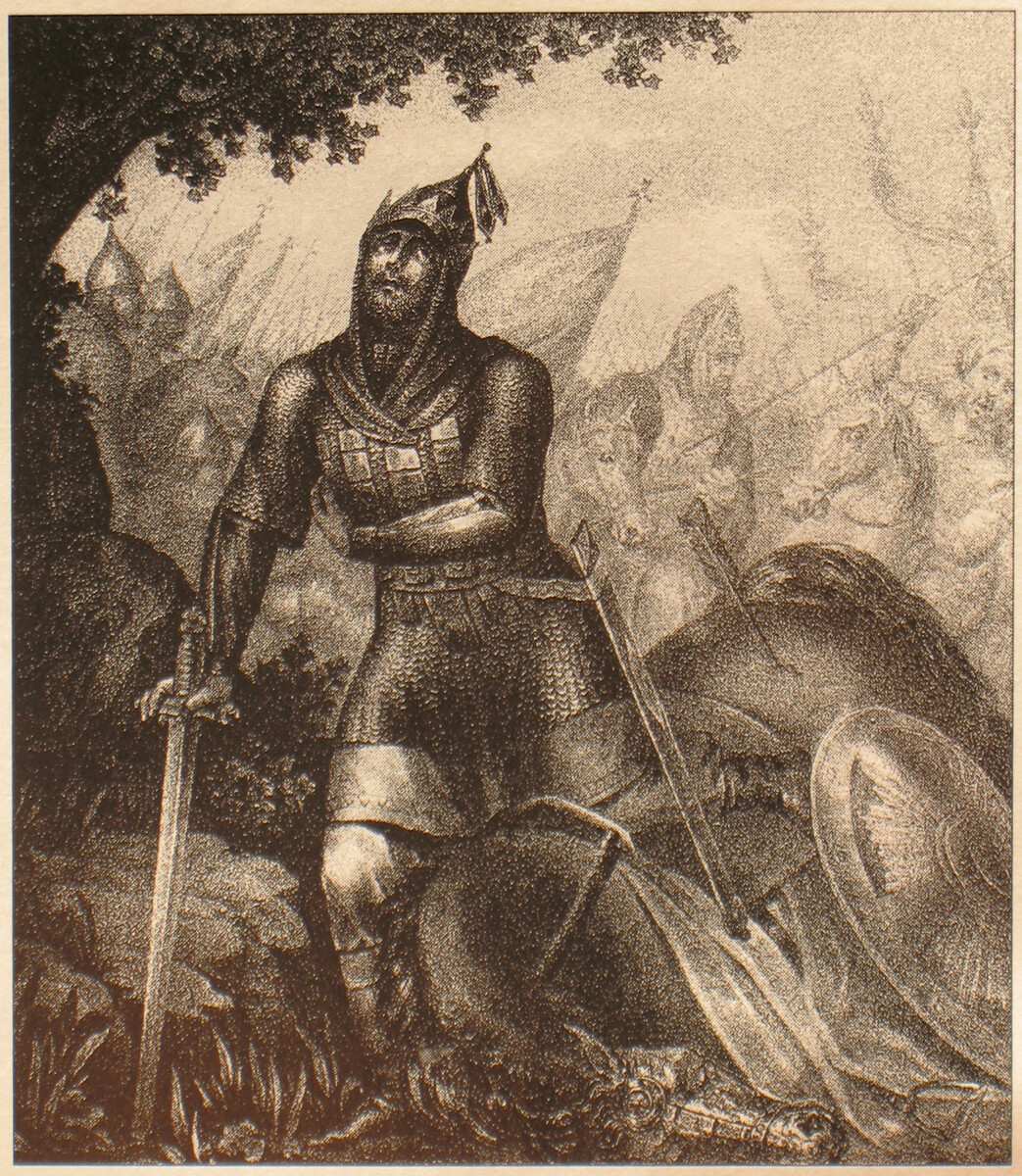

The Death of Grand Prince Sviatoslav I of Kiev. 972 (From Illustrated Karamzin),1836.

Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty Images“When Svyatoslav grew and matured, he began to gather many brave warriors and was swift as a pardus and fought much,” the chronicle ‘The Tale of Bygone Years’ reports: “During the campaigns, he carried neither oxcarts nor cauldrons behind him, nor cooked meat, but thinly sliced horse meat or animal meat or beef and roasted it on coals, so he ate; he had no tent, but slept spreading a covering with a saddle in his head,” The same were all his other warriors. And he sent [envoys, as a rule, before the declaration of war] to other lands with the words: “I am coming to you!”

In the year 972, Svyatoslav Igorevich was returning from a military campaign to Constantinople, when, on Dnepr thresholds, he ran into an organized Pechenegian ambush. Only a small part of his army made it home and from a skull of the killed prince, Pechenegian khan Kurya made a bowl for drinking.

The Battle of Kulikovo, 1849.

Adolphe YvonOn September 8, 1380, the united Russian army under the command of the Moscow Prince Dmitry Ivanovich encountered an army of the Mongolian temnik (warlord) Mamay in the place where the Nepryadva River flows into the Don River at the Kulikovo Pole (not far from Tula). Being under the power of the Mongols for almost a century and a half, Russia finally got a chance to gain political independence.

According to the Kulikovo Battle chronicle: “When they were fighting, from the sixth to the ninth hour, like rain from a cloud, the blood of the Russian and pagan princes followed and countless numbers fell dead on both sides. And a lot of Rus’ were beaten by the Tatars and the Tatars - by the Rus’. And the corpses fell on corpses, the Tatar body on a Christian body; here and there, it was possible to see how the Rusin chased the Tatar and the Tatar pursued the Rusin.”

In contrast to his vis-a-vis, Dmitry Ivanovich did not watch the battle “from the high hill”. Swapping his princely garb with a boyar named Mikhail Brenok, he fought as a simple warrior. “The grand duke himself had all his armor dented and punctured, but there were no wounds on his body and he fought the Tatars face to face, being ahead of all in the first fight. Many princes and colonels not once spoke of it: “Prince, lord, do not aspire to battle ahead, but be behind or on a wing, or somewhere in an extraneous place.” But he answered them: “How can I say: ‘My brothers, let us all move together as one’ and I shall hide my face and hide behind?”

The Mongols suffered a crushing defeat and the prince himself was nicknamed ‘Donskoy’ for his victory. An important step toward the liberation of the Russian lands from the oppression of the Horde was made, but it took another hundred years before it finally became a reality.

Portrait of Peter I.

Jean-Marc Nattier / HermitageFor more than twenty years, Russia fought against Sweden in the so-called Northern War, which resulted in it becoming a powerful empire and joining the group of great powers of Europe. The architect of this victory was tsar Peter I, who, more than once, personally led his troops into the thick of fierce battles.

“Warriors! The hour has come which will decide the fate of the Fatherland. And, so, you should not think that you are fighting for Peter, but for the state entrusted to Peter, for your family, for the Fatherland, for our Orthodox faith and church. Nor should you be embarrassed by the glory of the enemy, who seems to be invincible, a lie which you yourselves have repeatedly proved by your victories over him. Have in the battle before your eyes the truth and God, who is victorious over you. But know of Peter his life is not dear to him, if only Russia would live in bliss and glory for your welfare,” These were the words the king said to his troops on the eve of the decisive battle of Poltava, July 8, 1709.

The siege of Swedish fortress of Nöteborg in October 1702 by Russian troops, 1846.

Alexander von KotzebuePeter I not only exercised general command that day, but also personally participated in the battles. When two Swedish regiments almost broke through the center of the Russian defense, the tsar immediately arrived at the dangerous site and personally led a counterattack, as a result of which the enemy was overturned and the breach liquidated.

On August 7, 1714, near Cape Gangut (Hanko Peninsula), the Russian fleet won the first victory in its history. Russian galleys broke through the dense fire of the enemy, after which the marines boarded the Swedish ships. And, again, at the cutting edge of the attack, as always, was the tsar himself.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox