In 1925, Soviet authorities, busy with the population’s health after the Revolution, destructive Civil War and hunger, established a sanatorium for kids to recover after tuberculosis.

The first camp consisted of only 80 kids who stayed in tents in the area of Artek River near the city of Gurzuf in southern Crimea. So, this is how the legendary Artek camp history started.

In 1928, the first buildings for kids appeared. And who knew then that the still operating camp would end up hosting around 1.5 million children up until now?!

In 1941, the children had just arrived at Artek for the first summer shift and, on June 22, World War II began for the Soviet Union. The very next day, two hundred Artek children were evacuated to the Altai mountains. Later, this camp would become the longest in history, as, for three and half years, the kids lived there under the camp schedule, helped soldiers’ families and the wounded in hospitals and collected scrap metal for tanks and planes.

The Artek itself was occupied and only liberated in April 1944, while already in the summer of the same year, the camp already welcomed a new batch of kids - who originated from Crimea.

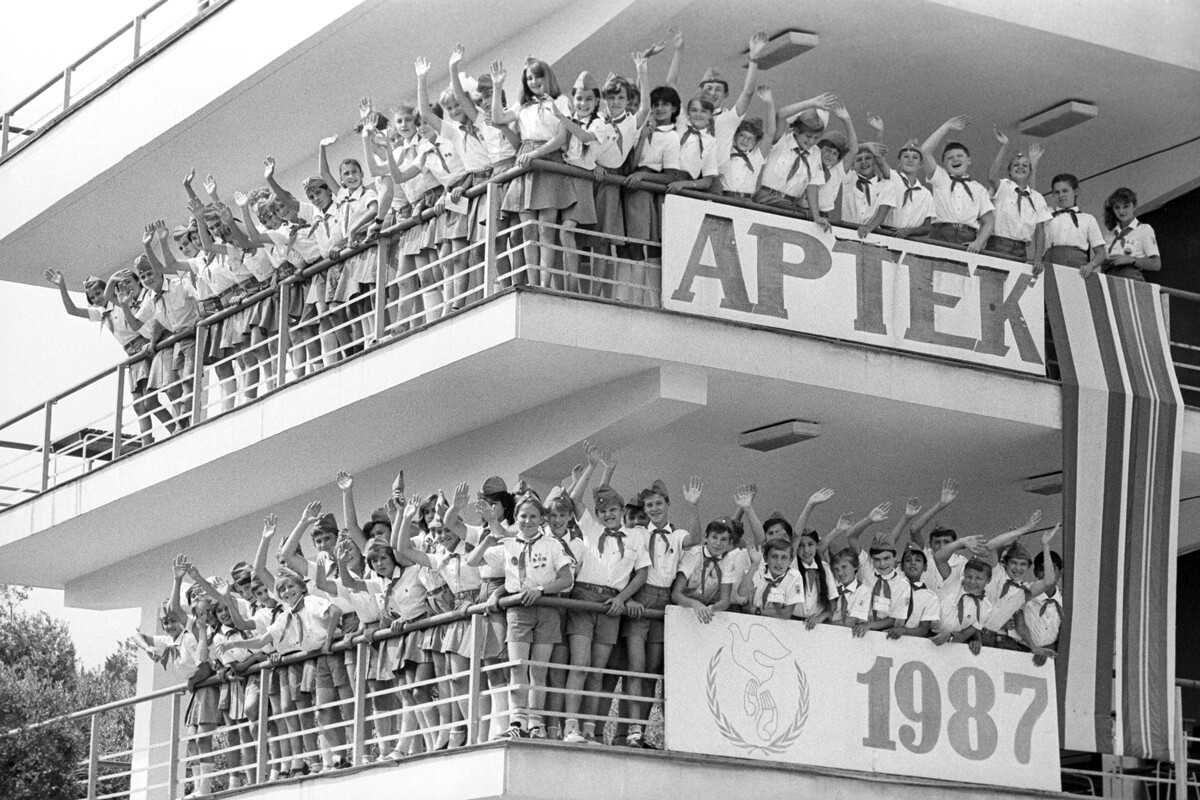

The 1960-70s was considered the golden era of Artek. The camp reached an international level and hosted thousands of kids from all over the Soviet Union, as well as from socialist friendly countries.

A big delegation of kids and young communists from Cuba used to visit the Artek.

And pictured below are Soviet and Indian kids on a Black Sea water cruise.

Many African kids were also invited to spend time on the Black Sea…

…as well as kids from Afghanistan.

A big event was a visit of American school girl Samantha Smith, who almost managed to halt the Cold War in the early 1980s.

The international community of children even signed peace declarations for kids of different countries: “Peace is life! War is death! We hate and curse war, we do not want nuclear and hydrogen bombs to explode, we do not want our fathers to die and our mothers to weep. We do not want to die. We want peace, clear skies and sunshine…”

The Artek also arranged international sports competitions for kids, as well as the all-Soviet pioneering meetings.

The Artek stadium could host up to seven thousand spectators.

Artek used to be a calling card of the Soviet pioneer movement and the very famous people were usually invited to visit the place. Among them were Soviet celebrities, such as the first man in space and the main hero of the time - Yury Gagarin…

…as well as legendary Soviet soccer goalkeeper Lev Yashin…

…and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev himself.

Moreover, a range of international guests also came to take a look at how the legendary Artek is operating. Among them were Indian leaders, including Indira Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (pictured below)…

…King of Nepal Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev and many other world leaders and celebrities.

The whole day was strictly scheduled. Morning started at 8 am with music playing loud around the whole camp.

The Pioneer horn became another symbol of Artek. The sound of the horn signified wake-up and bedtime and the pioneers also blew the horn at noon and on important occasions.

The must-do thing after kids wake up are morning exercises that should be done before breakfast.

Breakfast started around 9 am and kids were on duty and helped set the tables.

Before midday, when the sun heat was not very hot, kids spent time on the beach.

Bathing was only allowed in groups and after a special signal and only for a limited time.

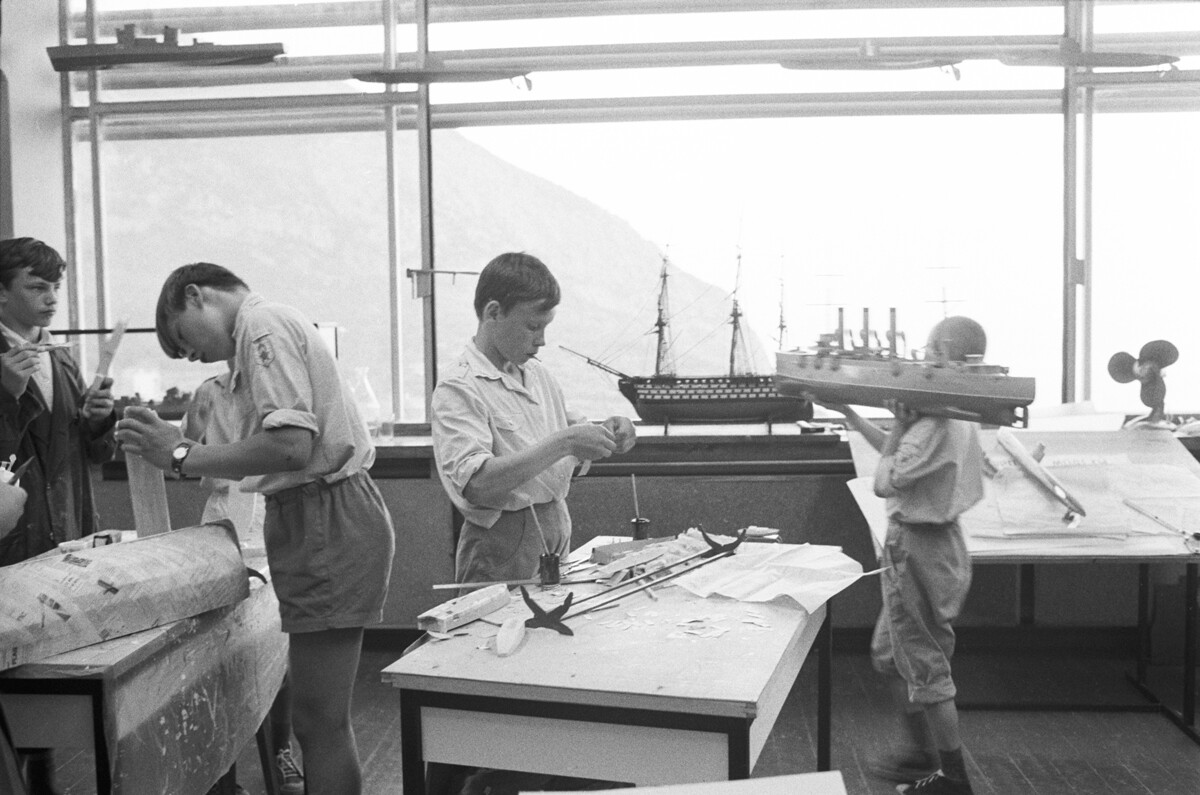

After spending around an hour on the beach, kids would dive into studies and hobby clubs, such as chess…

…shipbuilding…

…automobile modeling…

…painting…

…and even model lunar rover construction!

If you think that a summer pioneer camp was about leisure, that’s not the whole truth. Children were busy every minute with a variety of things.

Then kids have lunch and, from 2 to 4 pm, they usually have a nap and a small after nap snack, the poldnik.

After 4:30 pm, when the sun is already not so active and strong, pioneers go to the beach again.

Before dinner (which was usually at 7 pm), kids had a little free time that they could spend as they wanted. (But never for loafing around). Bedtime usually was horned around no later than 11 pm.

Sometimes, pioneers were also taken on guided tours around Crimea - in Yalta, Sevastopol and other great sightseeing spots. Pictured below are kids in front of the iconic Swallow’s Nest castle.

One of the favorite festivities of kids was Neptune Day, which has roots in the sailors’ celebrations of crossing the equator known as the line-crossing ceremony. Usually, in Artek, there was a costumed performance with dances and songs. Campers forcibly bathe or pour water on each other and, of course, bathe in the sea.

The camp batch usually lasted for 21 days and its end was usually marked with a concert and mass activities.

The final night had a nice tradition of a “pioneers’ fire”, where departing kids gather around the fire, talk, share secrets and feelings and sing songs.

And, of course, none of the camps could end without tears. Spending 21 days together, kids couldn’t handle the emotions of the fact that they need to go their separate ways and have to wait until next year or worse, never meet again.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox