To die or to be sent to do hard labor because of potatoes – that was indeed the bitter fate of some mid-19th century Russian peasants, when the so-called “potato riots” broke out in the Russian Empire.

In the town of Dolmatov (present-day Kurgan Oblast), peasants captured a local volost (a traditional administrative subdivision) head (an elected official), beat him, stripped him naked and tried to drown him and three clerks in the river. The officials had to take refuge in the monastery and only blanks fired from the monastery’s cannons cooled the fervor of the crowd.

The Uspensky Sobor in Dolmatov monastery

S. Prokudin-Gorsky / Public domainIn the village of Baturino, Shadrinsk Uyezd, the volost heads, priests with their wives and church servants – over 150 people – took refuge from the rebellious peasants in the church, which the peasants began to storm. The defenders had to shoot to kill with rifles.

In the Kargopolskaya volost of the same county, the peasants - both Old Believers and Nikonians – attacked the priest and deacon, poured ice-cold water over them, forced them to eat soil and demanded a “purchase charter”, according to which the peasants were supposed to plant potatoes.

Of course, it was not only the potatoes, the planting of which really began to be forcibly introduced by the authorities, that was the cause of the unrest. But the peasants, who called the tubers (the swollen underground roots of a plant, ie. the potato) ‘devil’s apples’, really made an unfamiliar crop into a monster – and made up a lot of myths along with it.

Picking potatoes, by Arkadiy Plastov, 1957

Russian State MuseumPotatoes came to Russia under Peter the Great, but they were common only on the tables of the aristocracy, as an exotic dish. However, in 1765, the Senate issued an instruction: “On cultivation of ground apples, called potatoes”, which contained recommendations on cultivation of the crop and was sent to all provinces together with potato seeds. But Russian peasants were in no hurry to cultivate the strange root vegetable. At first, poisoning by solanine was common – peasants unknowingly ate the fruit (berries) of potatoes, unripe tubers or sprouted potatoes. Perhaps because of this, the “ground apple” in the Russian environment began to be nicknamed ‘devil’s apple’.

Revolts against mandatory potato planting took place in the 1840s in the Ural provinces Perm and Vyatka and the revolts were not among the serfs, but among state-owned peasants governed by the Ministry of State Domains headed by Count Pavel Kiselev, established in 1837. These peasants did not belong to landlords (serfs) or the tsar (appanage peasants), but were called ‘free villagers’ who paid tributes directly to the state.

"Peasant lunch in the field," by Konstantin Makovsky, 1871.

Taganrog Art Museum / Public DomainAnother author of the reform of the state peasants, which began with the creation of the Ministry in 1837, was Count Yegor Kankrin, Minister of Finance (state peasants were under his authority until 1837). Yegor Kankrin was of German descent and spoke Russian with a thick German accent. Minister Pavel Kiselev was a true European by upbringing, even keeping his personal diary in French. These Europeanized officials believed that, as historian Igor Menshchikov writes: “The people are dark and afraid of improvements and related innovations and, therefore, need constant tutelage from the state.” Ministerial officials were put in charge of managing the state peasants. The Ministry provided the elected officials of local government – volost heads and their clerks – with uniforms with shiny buttons. The peasants did not like it at all, as they paid salaries to these civil servants from the funds of rural communities. All of this led to riots.

In 1840, the Ministry issued a decree on compulsory potato planting on state lands and, where it was not available, on communal lands. The peasants in several counties began to refuse to plant potatoes and, even more so, to revolt, as there were absolutely insane rumors circulating among them.

Monks at work. Planting potatoes. 1910.

M. Prokudin-Gorsky / Public domainThere were many Old Believer communities and settlements in the Ural provinces by the end of the 17th century and Old Believers were always known to spread rumors about the intrigues of the government among the peasants. In addition, Old Believers flatly refused to grow potatoes and include them in their diet, calling them ‘dog eggs’.

The Old Believers began spreading some ridiculous rumors in the peasant community. All free peasants would be sold to some landlord called ‘Minister’ or ‘Kulnyov’ (a distorted ‘Kiselev’), who would force the peasants to plant potatoes and peasant women – to weave cloth. The document for the sale of the peasants was the “purchase charter”, which allegedly had a “golden line”, a sign of its authenticity. If this document is taken away from the officials, the peasants retain their freedom.

Count Pavel Kiselev by Frantz Krueger, 1851

Public DomainIn the Klevakinskaya volost on Easter in 1842, the peasants searched the priest’s house for the charter and when they couldn’t find it, decided to go and drown the priest. He, however, managed to hide in the bell tower, where he spent more than three days. “Come down from the bell tower, father Jacob, give us our charter; you may be innocent, against your will you may have hid it. Destroy the charter, live with us [in peace] as before,” the peasants appealed to him. When this did not help, the peasants took his family hostage and hung his one-year-old son by the legs. When the priest came down, they tied a rope around him and dragged him from one bank of the river to the other, however, this also didn’t help in finding the charter. Only a military team that appeared just in time saved the priest from a public execution. In another case, a village clerk was dragged over broken glass and nailed to a fence in search of the charter, which resulted in his death.

Why did the people’s anger also turn to the clergy? First, the priests personified the government, because they announced the orders and decrees from the pulpit. Second, historians believe that attacks on the clergy were sometimes directly aided by Old Believers: for example, in the village of Kargopolskoe, the revolt began when a raskolnik (an Old Believer) rushed into a church and attacked the priest, beating him and tearing his vestment.

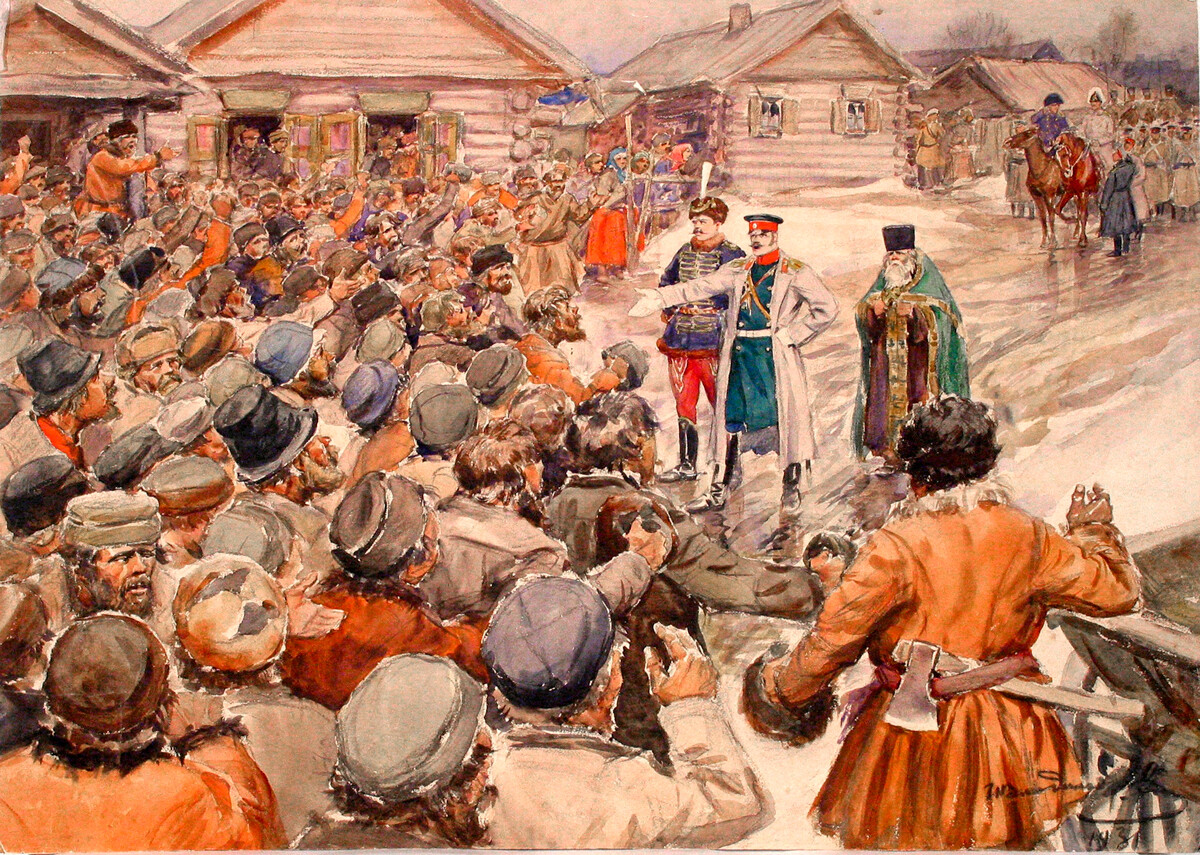

"The Peasant Riot," by Ivan Vladimirov, 1931

Public DomainIn 1843, the riots had a wider scope. Thousands of peasants with scythes and pitchforks flocked to the village of Baturino, south of Shadrinsk. “The world is sold! The elders say: fight the Minister, who sent money to the clerks and priests and, in exchange, demanded to sow potatoes for his own benefit!” This was the mood of the peasants. The few officials guarded by a dozen soldiers were forced to take shelter in the local church until a regiment came, which dispersed the rebels.

Almost everywhere in the Urals the riots were suppressed by the troops and the trials were carried out by military field courts. Ordinary peasants, as a rule, were not exiled, but were sentenced to corporal punishment – flogging. The instigators of riots were whipped with spitsrutens. This was a heavier punishment in which victims stripped to the waist ran the gauntlet between two lines of soldiers, who beat them with metal rods. A sentence of 10 to 12 such runs could be fatal. After the execution, the instigators were sentenced to fines and exile to Siberia or to the construction of the Bobruisk fortress. In addition, the riots themselves subsided with the beginning of the agricultural year – it was necessary to start the sowing season.

The Bobruisk fortress in 1918

Public DomainAnd, in 1843, the forced planting of potatoes for state peasants was finally abolished. As a result, by the end of the 19th century, more than 1.5 million hectares of potatoes were sown in Russia and the tuber became a part of the peasant diet, especially in provinces with little land. But not with the Old Believers, who refused to eat ‘dog eggs’ until the second half of the 20th century.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox