Noblemen in Russia would not find it difficult to understand the situation that numerous modern Russians find themselves in, with their several credits and multiple debt restructuring. A genuine debt pit was actually par for the course for a great number of the class in late 18th and early 19th centuries in Russia. This never stopped them spending lavishly, however - which might include building a new greenhouse or another lavish trip to Europe. However, it was about more than just living large.

The notion that Russian nobility was swimming in riches is actually false, regardless of their titles and privileged position with the tsar. There were actually plenty of noblemen with property and real estate incomes so small that it was barely enough for a socialite lifestyle and a few quality frocks.

Nevertheless, the titles they held necessitated an appropriate lifestyle. And living up to that reputation was a massive drain on income. There was the food, the clothes, books and decorations, education, taking care of relatives, gifts for important persons, travel and so on. And ‘grand tours’ of Europe were a must, often with the aim of gaining knowledge from famed specialists - including in music, horseback riding, philosophy, economics and so on.

"Bank collapse"

Vladimir MakovskyEven charity - a seemingly voluntary pursuit - could become a serious contributor to debt. “Another 15 rubles for last year’s debt,” Russian Chancellor Aleksandr Vorontsov wrote in his income and expense notebook.

Construction was by far the most draining of all things. However, owning real estate was a sign of prestige - and the more of it, the better.

Read more:How Russian nobles lost money, wives and honor in card games

A nobleman usually had several sources of income (an estate, the peasants working it, as well as a salary for government service). But, estate income only came twice a year, at best: serving noblemen lived in cities and the estates were provincial, with huge distances making it difficult to travel only to fetch the cash from running the property.

"At the tavern"

Vladimir MakovskySalaries were also given out rarely - only three times a year. And with a country so reliant on agriculture, years of bad harvest resulted in the landlord having to pay the peasants out of his own pocket. Salaries could also be cut or withheld. For instance, an assessor - a very coveted position - only made 300 rubles a year in the 18th century; a notary - 150-200, on average; and judges earned 600 rubles. Meanwhile, a pood (ca. 16.3 kg) of pork cost 40 kopeks; the same amount of the best wheat - 30 kopeks; a hat was 2 rubles and an exquisite livery with gold braid, worn by lackeys, cost an astonishing 70 rubles. Now, imagine that you only get paid a few times a year and have no way of telling the exact sum that’s coming. That is how we arrive at the noblemen always ending up in debt. What’s worse, many had almost no idea of the sums they actually owed.

A nobleman’s social status afforded him access to easy credit lines, which became a thing in the early 18th century. The first Nobelmen’s Bank, which only lent to members of the class, appeared in 1754. In 1769, foreign credit lines appeared. As a result, Russia is flooded with money that was lent and spent with great ease.

"Bargaining"

Nikolay NevrevAround that time, the new institution of borrowing from the state appeared, involving a percentage rate. That money could be spent on anything - the state never ran checks.

Meanwhile, borrowing from the bank amounted to borrowing from the state anyway. People would also use those loans for refinancing existing credit lines, creating a cycle.

"Landlady"

Konstantin MakovskyA nobleman could borrow from lower castes, such as tradesmen and even his own peasants. He could easily put goods on a tab, as merchants knew that, in the event of death, the debt would likely be covered. Besides, having a nobleman shop at your establishment added prestige.

An estate could have “two cash desks” - the owner’s (collected by peasants for the landlord) and the peasants’. If the owner ran out, he would simply borrow from the peasant till, paying them back later.

There was an unspoken order in which the noblemen covered their debt. Firstly, to the state, then to other noblemen (not the inner circle), then merchants, relatives and, finally, peasants.

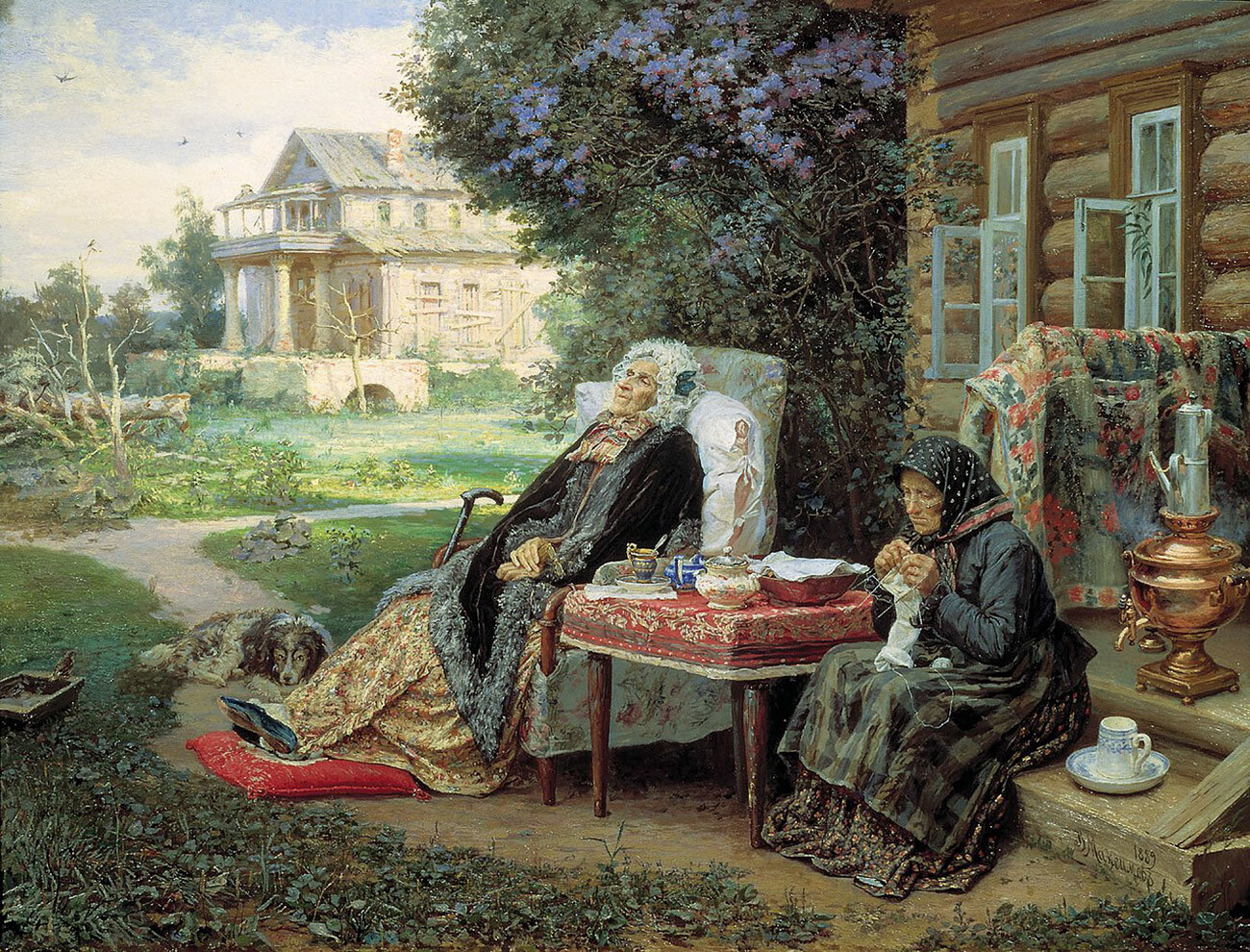

"All in the past"

Vasily MaksimovTo keep track of the spending, income and expenditure notebooks existed. But not everyone had one. In actuality, all of the nobleman’s debts were often made clear only after his passing. Relatives would even post newspaper announcements with news of the death: “So and so has passed. Whoever has any outstanding financial business is required to make it known in the next six months.”

Liquidating debt could be a difficult and lengthy process, often dragging on for years, with children having to take care of repayment. Large debt was often liquidated by way of property sale. Noblemen took care of their reputation and a debtor’s reputation could become a problem for the offspring: it was more difficult to marry off the daughter of such a man and harder for his son to advance through government ranks and so on.

"Literary reading"

Vladimir MakovskyUnderstanding that the Russian nobility fell victim to their own status, the Free Economic Society (the first public organization in the Russian Empire) recommended that they place at least some limits on their expenditures - for instance, not stopping buying good wine, but diluting it with quality water; also, knowing that keeping account of flour isn’t always easy - to purchase bread, rather than make it at home; it was also best not to build estates, but rent them: construction could easily result in financial ruin. However, these recommendations weren’t always followed to the ‘T’: many preferred to push the debt issue under the rug, until something truly critical happens - which often meant that debts would often end up being repaid only in the event of death.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox