The most famous exchange of captured intelligence agents during the Cold War took place on February 10, 1962, on the Glienicke Bridge in Berlin, which marked the border between the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and West Germany. It was there that Rudolf Abel, a resident agent of Soviet intelligence in the United States, was exchanged for Francis Gary Powers, an American pilot shot down over Soviet territory.

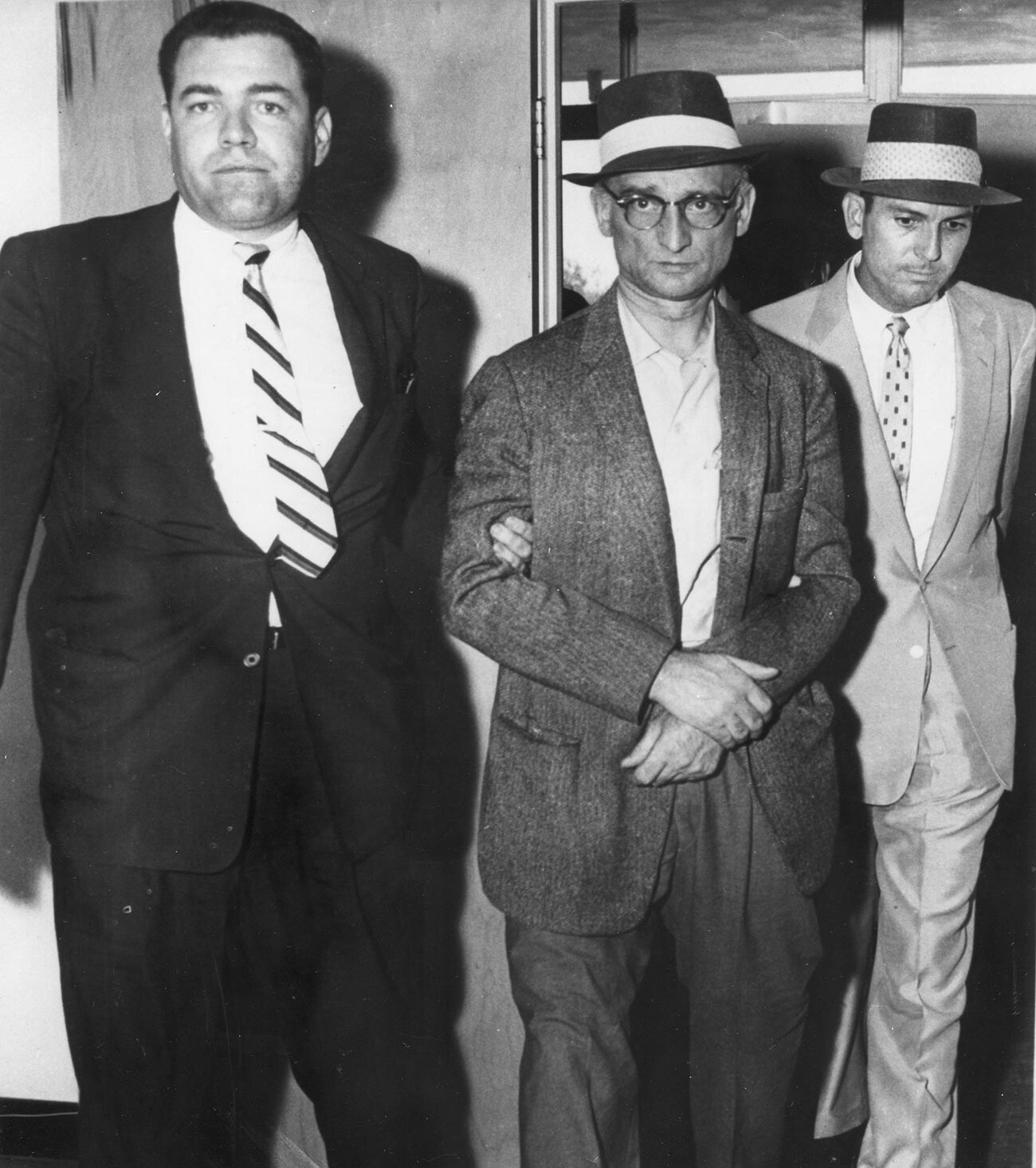

Rudolph Abel (center) arrives at court for his arraignment on espionage charges, New York, July 1957.

PhotoQuest/Getty ImagesRudolf Abel (real name William Fisher) had been working in North America since 1948. There, he obtained information about the economic and military capacities of the United States (including nuclear) and set up and masterminded spy rings. In 1957, he was arrested by the FBI as a result of betrayal by one of his Soviet colleagues.

The intelligence officer categorically refused to cooperate with the American intelligence agencies and was sentenced by a court to 32 years in prison for espionage. “Everything that Abel did, he did out of conviction, and not for money. I would like us to have three or four people like Abel in Moscow,” CIA Director Allen Dulles said about him.

Francis Gary Powers holds a model of a U-2 spy plane as he testifies before the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesThe USSR planned to get Abel released by handing over to the Americans pilot Francis Gary Powers, who had been captured when his U-2 spy plane was shot down over the USSR on May 1, 1960, while taking photos of strategically important installations.

The Americans, however, considered the deal unequal. Moscow ended up having to give them several more captured agents in exchange for such an important figure as Abel.

Soviet intelligence officer Konon Molody had been working in Britain since 1955, posing as a businessman named Gordon Lonsdale. He managed to recruit British naval code clerk Harry Houghton and, for years, supplied Moscow with secret information on the state of the British submarine fleet. At the same time, Houghton himself believed that he was working for U.S. intelligence (the allies spying on one another was nothing out of the ordinary at the time).

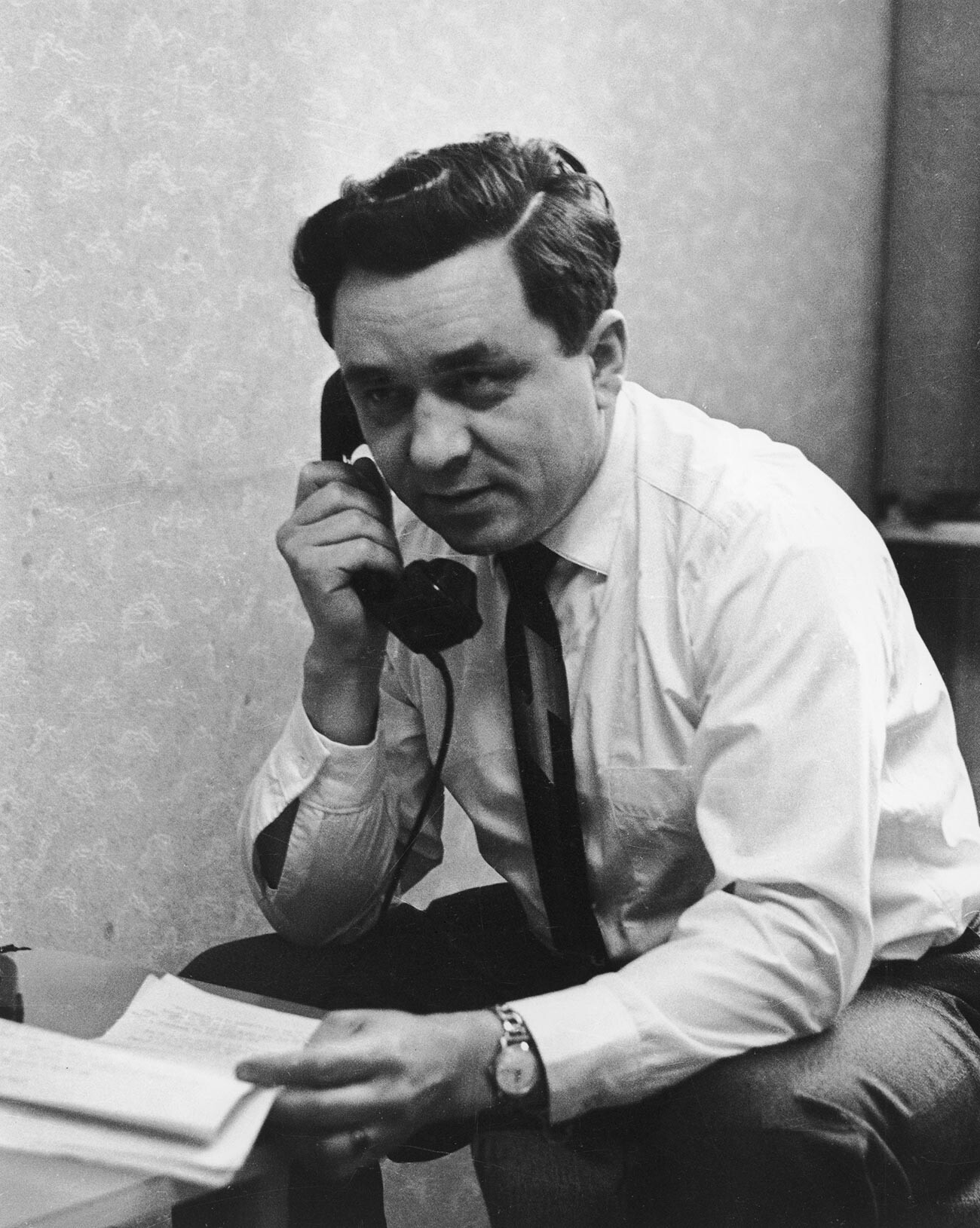

Gordon Lonsdale in East Berlin.

Sunday People/Mirrorpix/Getty Images/Getty ImagesMolody/Lonsdale also turned out to be a good businessman. Shortly before his exposure in 1961 (he was betrayed by a Polish defector), the intelligence officer received a commendation from Queen Elizabeth II in recognition of his “major accomplishments in the development of business activity for the benefit of the United Kingdom”.

The USSR and Britain agreed to exchange Molody for MI6-recruited British businessman Greville Wynne, who had acted as intermediary for Oleg Penkovsky, a GRU military intelligence colonel working for the Western special services. Until Wynne and Penkovsky’s arrests by the KGB in 1962, the latter had managed to pass more than 5,500 secret documents to Washington and London, as well as revealing the names of hundreds of Soviet agents. Penkovsky was shot by firing squad on May 16, 1963.

Greville Wynne being escorted by policeman after arriving back home from the Soviet Union, at Northolt Airport, England, April 22nd 1964.

Dennis Oulds/Central Press/Getty Images/Getty ImagesAt half past five on the morning of April 22, 1964, two cars met at one sector of the border between the West Germany and GDR. “Four persons emerged from the ‘other’ car,” recalled Molody. “They included Wynne. He looked scared and miserable, quite unlike the retouched photographs printed in the newspapers. Two men standing at his side were lightly supporting him. It seemed that were they to let their hands drop, he would collapse straight onto the road… Those involved in the exchange lined up facing each other along the centerline of the road. The Soviet consul pronounced the word ‘Exchange’ in Russian and English and before I knew it I found myself in the car. In ‘our’ car. With friends. Finally with friends.”

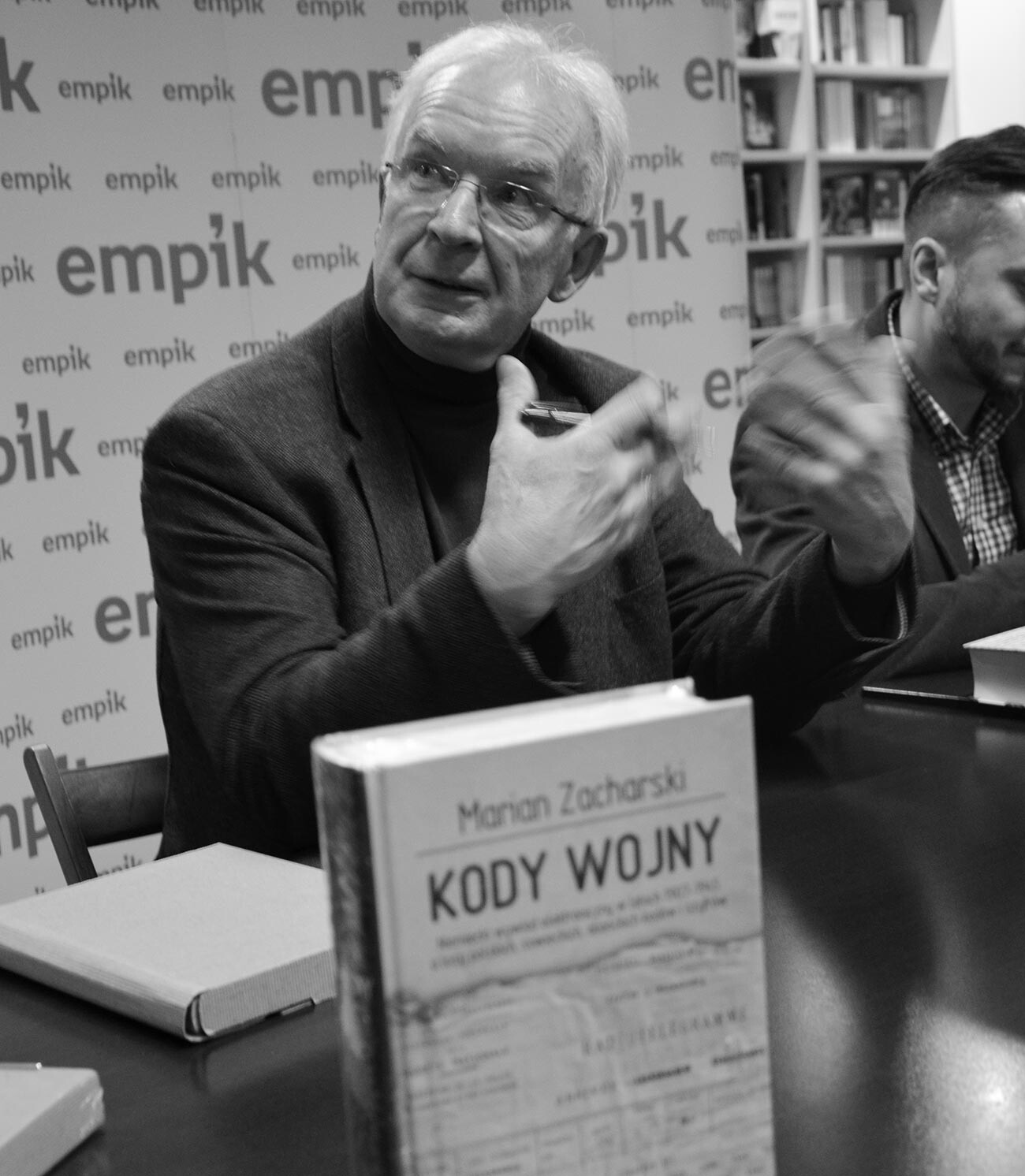

Marian Zacharski was the most successful Polish intelligence officer in history. In 1977, he settled in the United States and began working for the Polish American Machinery Corporation, a machine tool company based in Illinois. Zacharski succeeded in gaining the confidence of, and recruiting, a leading expert at the military-industrial aircraft maker ‘Hughes Aircraft’. This was William Holden Bell, whose house was near to where Zacharski lived.

Marian Zacharski.

Silar (CC BY-SA 3.0)/Getty ImagesThe intelligence officer regularly passed secret information to Warsaw regarding the F-15 fighter, the TOW anti-tank missile, the Phoenix air-to-air missile, the M1 Abrams tank, the Patriot missile system and other weapons. Poland expeditiously passed this top-level information on to the USSR.

In 1981, Marian Zacharski was discovered and arrested by the FBI and, from that moment, Polish intelligence sought unsuccessfully to free their most valuable agent. In the end, the GDR and Soviet Union were brought into the negotiations and it was the latter that organized an exchange.

The Glienicke Bridge.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesOn June 11, 1985, the largest spy swap of the whole Cold War era took place. Twenty-three captured Western special services agents set off along the ‘Bridge of Spies’ (as the Glienicke Bridge became known) for the West, while four Eastern bloc intelligence operatives headed in the opposite direction, including Zacharski.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox